Edward Said is someone who wrote in the service of life. His formulations had a profound impact, both subtle and explicit, on a wide range of fields and interests. It’s not too much to say that his body of work has irrevocably altered the way we think about the power of narrative and representation, as well as the relationship between knowledge, culture, and colonial force.

Layla AlAmmar

In her 1919 biography of Egyptian feminist Malak Hifni Nasif, the litterateur May Ziadeh says, “life has a way of producing those who will be in her service.” She goes on to explain how there are men and women who are born into a particular set of circumstances, who possess innate gifts, who are confronted by pressing conditions or an unbearable status quo, all of which compel them to say what has never been said before. They forge new trails, formulating groundbreaking knowledge or innovative modes of cultural and sociopolitical resistance. They emerge in a nexus of word, action, and passion to present life with what she finds herself in need of. The Palestinian American academic, critic, and political activist Edward W. Said (1935-2003) was one such soul — a man whose background, life trajectory, intellectual capacity and talents coalesced to make him one of the great thinkers of our time.

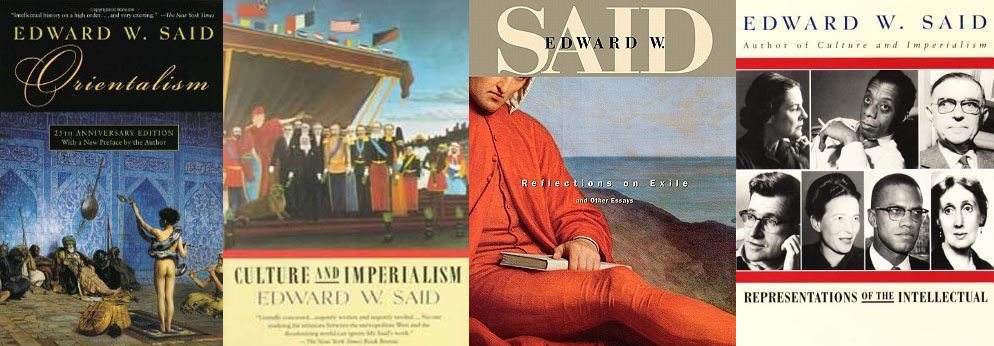

This September marked 20 years since Said’s passing, leaving behind a legacy which has cast a long shadow across the Arab world and, in particular, the role of the intellectual in public life. Said authored dozens of books, essays, and lectures on topics ranging from the responsibility of the critic, the poetics of decolonization, classical music, the relationship between culture and imperialism, the agonies of exile, and the Palestinian cause. His landmark work Orientalism (1978) became a foundational text of postcolonial studies, influencing generations of scholars, writers, and artists. The book fundamentally reshaped our understanding of the networks linking power, knowledge, narrative, and perception. More importantly, it showed us how these networks operate on the flesh and blood landscape of history and, by extension, present-day realities.

As Said’s popularity grew, so did his commitment to his burgeoning role as a public intellectual. He wrote newspaper articles and appeared in television interviews to speak on matters of representation, Arab/Muslim stereotypes in the media, and America’s imperial ambitions in the Middle East. In packed lecture halls he debunked popular myths, such as Samuel Huntington’s war-mongering cry of a “clash of civilizations,” and skewered orientalists for their lazy claims and shoddy scholarship (the shade he routinely threw at Bernard Lewis is, for me, a particular source of delight). Concurrently, his sense of duty towards the Palestinian struggle increased, and he served for 15 years as an active member of the Palestinian National Council before parting ways with the leadership in 1993, over what he rightly saw as the surrendering of Palestine with the signing of the Oslo Accords.

I’ll not go into detail about Said’s life and work for these have been covered across a range of books and articles. Instead, I’d like to focus on what Said has meant to me — as a writer, an academic, an Arab, and as someone with a keen interest in the dialectic of power and representation. If you are lucky enough to ever be gripped by the workings of an exceptional mind, you’ll find that the impact happens on multiple levels — intellectual, emotional, ontological — and the intimacy with which you begin to comprehend them washes over you in waves. When you find yourself in love with someone’s mind, what you desire is complete immersion.

Like many others, my first exposure to Said came with Orientalism. I read that book at the vulnerable age of 19, and it resonated with me at a very visceral level, by which I mean that certain passages rang true even if I didn’t completely understand what I was reading (for all that I adore his prose, Orientalism is quite dense in parts). I read the book at an age when you begin to interrogate things you presumed were a given. I was questioning who I was and who I thought I might want to be; I was wrestling with my faith and what it was I truly believed in; I was reading more widely and deeply than ever before, leading me to the realization we all have (or should have around that age), which is that we really don’t know very much at all. I’d been writing fiction for as long as I could remember, but this was also the time when the ambition for more began stirring in my breast. It was when I started entertaining the idea that a day might come when I would walk through a bookstore and find my own novels on the shelf.

I wondered what those novels would look like. What would they be about? Would they be set in my home country of Kuwait? Would they deal with the frustrations my friends and I felt in a society struggling with what it means to be modern? I wondered how a soccer mom in Dallas picking up my novel at her local Barnes & Noble might receive it. In Orientalism Said says, “it is a fallacy to assume that the swarming, unpredictable, and problematic mess in which human beings live can be understood on the basis of what books say; to apply what one learns out of a book literally to reality is to risk folly or ruin.” And yet I knew, instinctively, that that was exactly what would happen. My novel would be understood as representing Kuwait in its totality. As the truth rather than a truth. Based upon it, assumptions would be made about an entire country, with its complexities and vastly differing sensibilities, and certain misconceptions might be confirmed and confidently tucked away. From Said’s book I understood, for the first time and with enormous depth, that there was an image of Kuwait already constructed in and by what we might simplistically call the “western world” and that it exerted tremendous power over any portrayal of my world that I might construct. In the introduction to Orientalism he calls this “the nexus of knowledge and power [that creates] ‘the Oriental’ and in a sense obliterat[es] him as a human being.”

Nineteen-year-old me drew a severe red box around the last part of that sentence.

In my naiveté I had believed in the empathic power of literature, in its ability to create solidarities and foster human connections. I thought everyone read novels the way I did — as partial representations rather than as some total and objective truth. It took me a long time to realize that where I had almost infinite images of, say, America or England, readers there had very few, if any, images of Kuwait. Where any college-educated Kuwaiti would be able to rattle off a list of American novels or English writers, what would the average American be able to say about us?… apart from how their army cousin was stationed in the country at some point or something. I began to see that it’s only through a multiplicity of representations (what Deleuze and Guattari, in Kafka: Towards a Minor Literature, call an “assemblage of enunciation”) that any semblance of “truth” might be approached. Said, for his part, was dubious about the entire enterprise, asserting that “representation is eo ipso implicated, intertwined, embedded, interwoven with a great many other things besides the ‘truth,’ which is itself a representation.”

It takes time for an idea like that to truly sink in, to think of truth itself as a representation that is constructed and circulated, received and consumed, or to conceive of it as something that travels far beyond its origins, that outlives the context which produced it. Consider the “great many other things” that are interwoven with representations: language, culture, history, political and religious leanings, all the known and unknown idiosyncrasies of the representer. These constructions don’t emerge from a vacuum, nor do they subsequently float in empty space. Rather, they inhabit what Orientalism determines to be “a common field of play [that has been] defined for them.” In his more charitable moments, Said conceives of representations (such as novels) as belonging to a family, existing in a kind of ecosystem of references and linkages. His thoughts on the nature of representation are some of his most insightful and had a profound effect on how I would conceive of my writings, both creative and scholarly, from that point on.

An intellectual’s work will always reward multiple encounters.

So gripped was I by Orientalism that I went on to read (and reread) nearly everything Said wrote — from Culture and Imperialism to Freud and the Non-European to Beginnings to his brilliant essay collection, Reflections on Exile. Immersing myself in his corpus showed me a few things, perhaps the most significant of which was that you cannot be content with an intellectual’s first utterance on a topic. Too often, it seems to me, references to some grand theory or statement begin and end with the first iteration of it — whether it’s Said’s Orientalism, Freud’s theories of mourning and melancholia, or Adorno’s claim regarding the writing of poetry after Auschwitz. These are but initial forays into extraordinarily complex spheres of interest and are in no way etched in stone. It’s not enough to stop there. It’s incumbent upon us to appreciate the totality of a great mind, to trace the genealogy of their thinking, the evolution of their statements on a given topic. It’s bad enough that in many quarters Said has been reduced to a single idea; what’s worse is that he’s been confined to the very first shape that idea took when, in fact, he returns to it multiple times over the course of his career — in interviews, in other books, in prefaces to subsequent editions of Orientalism and in standalone essays.

My immersion in his writings also hammered home for me the value of rereading texts. An intellectual’s work will always reward multiple encounters. The truth is that when we read, we never read with total concentration. There are always passages that our eyes will merely take in while the mind wanders off. More than that, we are not the same person with each reading. We will have grown, read other books, discovered other concepts, had experiences and met new people who enrich our lives. All of this will influence how we take in a text, what we get from it, what resonates most strongly at any given moment in time. My copies of Said’s books register a topography of affect. In different colored highlighter pens, stars and exclamation points, lols and notations in the margins, I can trace the impact his words have had on me through the years. I can see clearly those illuminations which I found useful for a novel or my scholarly work or paragraphs that simply blew my mind.

I realize that at this point I run the risk of sliding into saccharine fawning, so let me acknowledge that Said’s work is not without its limitations and blind spots. Orientalism has had its fair share of criticism — some legitimate, some utter nonsense. His views on Arab literature are restricted to mostly canonical work, such as that of Mahfouz, Kanafani, and Tayeb Salih, and he displays shockingly little knowledge of women writers and intellectuals, whether Arab or not. In fact, in his 1993 Reith lectures, Representations of the Intellectual, only Virginia Woolf is mentioned. These weaknesses don’t warrant dismissal of Said, of course, but they do tell us we need to proceed with caution when applying his thought to the sprawling mess that is the contemporary Arab world, as well as in thinking about our place and sense of being (as writers, academics, artists, etc.) within it.

As a public intellectual Said modeled how one ought to hold fast to their principles, even when it complicated matters; indeed the vocation of the intellectual, he writes, ‘involves both commitment and risk, boldness and vulnerability.’

By his own admission, Said found no topic so tedious to discuss as identity, which is ironic since, next to representations, his writing on the subject played such a large role in my conceptualization of identity, whether in my scholarly work, novels, or for my own sense of self. My first encounter with these ideas came towards the end of Culture and Imperialism. He talks about the push and pull between centers and peripherals, between hegemonic powers and those they impinge upon. These forces are pivotal in shaping who we are and who we become. He says flashes of brilliance result from such “contrapuntal” living, from our awareness of and resistance (in literature, in art and film, in politics) to “the imperialist power that would otherwise compel you to disappear or to accept some miniature version of yourself as a doctrine to be passed out on a course syllabus.”

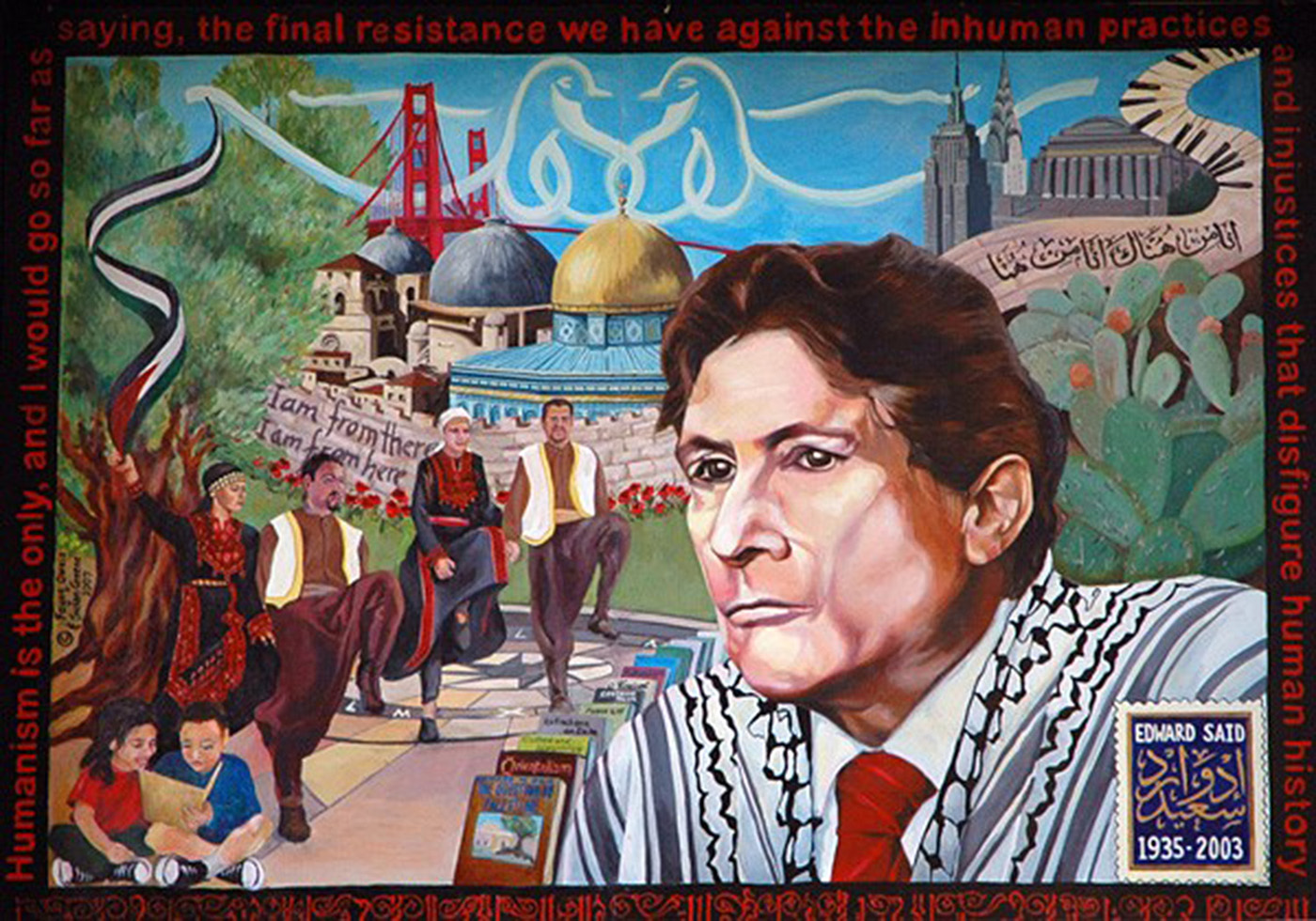

Loathing the notion of labels or fixed parameters, identity for Said was dynamic, elastic, in constant flux and motion. He quotes Iranian intellectual Ali Shariati who sees our identity as “a struggle, a constant becoming,” that we are all “migrant[s] within [our] own soul[s].” Mahmoud Darwish, in his elegy to Said, expresses a similar sentiment, claiming that, like the wind, identity “has no ceiling. It has no abode… He says: I am from there. I am from here. But neither am I there, nor here.” Further ventriloquizing Said, he echoes the truth that we are all ultimately responsible for who we become, for identity, he says, is “the innovation of the individual to whom it belongs.” It’s an unending process of discovery, a tapestry we never complete and perhaps are not meant to.

I opened this piece saying that Said is someone who wrote in the service of life. His formulations had a profound impact, both subtle and explicit, on a wide range of fields and interests. It’s not too much to say that his body of work has irrevocably altered the way we think about the power of narrative and representation as well as the relationship between knowledge, culture, and colonial force. More than that, he offered strategies for counteracting these forces (contrapuntal reading, worldliness) and urged us to go beyond trifling assertions of identity, to not be content with merely having a seat at the table, but to do something with it. As a public intellectual he modeled how one ought to hold fast to their principles, even when it complicated matters; indeed the vocation of the intellectual, he writes, “involves both commitment and risk, boldness and vulnerability.” Said recognized that, in every sense of the word, “intellectuals are of their time, herded along by the mass politics of representations embodied by the information or media industry, capable of resisting those only by disputing the images, official narratives, justifications of power circulated by an increasingly powerful media — and not only media, but whole trends of thought that maintain the status quo, keep things within an acceptable and sanctioned perspective on actuality.” Time and again, Said would embody this ethos in his writings and public utterances.

But where does this leave us? All our atomized Arab souls, crushed over and over by unrelenting, gargantuan forces. We were never short on intellectuals in the past, men and women who were able to harness the seething political, social, and psychical energies around them, to capture the screaming consciousness and transmutate it into language, image, and form. I’m thinking of Rifa’a Rafi’ at-Tahtawi and Abbas al-Aqqad, Georges Tarabichi and Mohammed Abed al-Jabri, Ghada Samman and Nawal el-Sadaawi, Elias Khoury and Ghassan Kanafani. Across their work not only can we trace the failures of Arab modernity but we can catalog resistance to totalitarianism, neopatriarchy, imperialism, sectarianism, and all the myriad factors that have derailed our progress over the decades. We are a people given to looking behind, more comfortable in the past. In other cases, we are too mired in the unbearable present to be able to see ahead into an increasingly hazy future.

Who are our public intellectuals of today? A friend asked me that question a few months back and I struggled to find an answer. What would an Arab public intellectual look like in today’s world? This world of knee-jerk reactions and lazy cynicism, a world that’s grown suspicious of — if not outright hostile to — intellect and impatient with nuance, a world so quick not only to point out a flaw in someone’s argument but to allow that flaw to eclipse the entirety of their intellectual output. It is a world of hyper-presentism, of now, of surface readings, of quick and concrete conclusions. It’s a world tailor-made for the pseudointellectual and grossly inhospitable to the true one.

This is no longer the world of Edward Said nor is it the world of Arab intellectuals of the past. It’s a world grown exponentially more complex by virtue of overwhelming digital connectedness, hypercapitalism, technological advances too rapid for moral reasoning, and all the excesses of neoliberal policies. In a post-ideological, post-truth world, who has life produced to be in her service? A few names come to mind: Alaa Abd El-Fattah, Mohammed El-Kurd, Samar Yazbek. They are souls who have put their lives on the line to say what must be said. Their work and writing are fused with and “remain an organic part of an ongoing experience in society: of the poor, the disadvantaged, the voiceless, the unrepresented, the powerless.” Comprehending the seen and unseen forces that press down upon us from all sides, the intellectual feels compelled to represent them in a way that speaks to their constituency first, followed by an ever-expanding audience. The intellectual bridges the gap between theory and praxis, a melding of word and action. In Gramsci’s words, it’s to tread the line between “the pessimism of the intellect,” which might otherwise cast you into melancholic despair, and “the optimism of the will,” which compels you to stand up and try again.

That is the life the public intellectual models for us. And in the end, that is the legacy they leave behind.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)

brilliant essay.

Brilliant, soul-searching essay.

Soul-searching and inspiring exploration of a master’s words and his guidance.