Censorship by the state, the social media mob, authors’ self-censorship, and the lack of books in bookstores all limit the range of titles available to readers. In the Middle East, poor distribution and an over-reliance on bookfairs, as well as the lack of clout by small independent publishers, determine both book sales and who gets published.

When we think about freedom in the context of books, we tend to think about state censorship — a serious obstacle impeding our access to reading material and a sadly increasing phenomenon. We generally understand censorship as a deliberate act undertaken to “kill” a book. It involves taking different sorts of actions to make certain books inaccessible — to make them disappear. Think of the autodafé, and all the burned books in history, an effort to erase all trace of them, to pretend they never existed. But what about the other factors that prevent our access to books? Would these count as a violation of our freedom to read?

Freedom is information

The majority of us have the naive view that, beginning with the author, there’s a long chain of actors all making sure that a book reaches its reader. We don’t really think about how this happens. We assume it just does. Most of us are hardly aware of how precious, and in fact rare, this is.

In most of the world, from Latin America to the African continent and the Middle East, this chain is either nonexistent or broken.

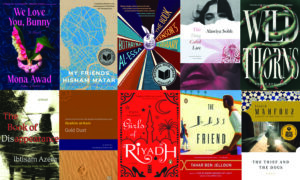

In the Arab countries, for example, there is a notorious lack of a solid distribution network for physical Arabic books. As a result, books circulate with great difficulty. A typical mainstream chain bookstore will tend to carry the most important local books (big authors, best sellers), especially the most recent releases. In some cases, a few backlist titles will be included. More generally books released by small, independent or more niche publishers won’t travel regionally. First novels or experimental books by, say, a small Egyptian publisher, will rarely make it outside Egypt, apart maybe to bookfairs.

Bookfairs remain the strongest regional distribution network for Arabic books. A couple months before the bookfair, publishers from around the Arabic speaking world will send containers full of their books to the fairground. Fairs offer a temporary space for a publisher to sell his books outside his country to a guaranteed audience of avid readers. They facilitate book travel as they don’t require a distributor to take care of the shipping, and/or customs clearance, or selling and dispatching the books to an (increasingly decreasing) number of bookstores. Fairs are the distribution network. Publishers make the rounds of the various fairs, visiting one Arab city/country per month and take their books with them. Readers and local booksellers visit book fairs knowing they’ll have the opportunity to source books they otherwise won’t have access to for the rest of the year.

In this case, it is not that some forces are intentionally preventing access to books — though of course some books are censored. Rather it is systemic, whereby structural factors are responsible for impoverishing the books on offer outside the fairs, and more importantly, as a result, impeding the accessibility of information about them as well.

Information about new releases and books in general comes in various forms: from publications such as blogs, newspapers, newsletters and reviews as well as from apps and sites such as Goodreads, Tiktok, YouTube etc. Fundamentally, it is all knowledge that readers gather on their own through simple exposure. And the more readers are exposed to a diversity of sites and a diversity of books, the more knowledge they are given access to.

Purple, green, blue, and yellow

Think about the diversity of books as though they were colors on a spectrum. Each color category is a literary genre, for example. Within each category there are various shades, as well as many potential combinations across categories, opening up a world of endless possibilities. Additionally, the ways in which these genres are used or expressed changes with time, depending on how people experiment with them, or on changing tastes and trends. For example, the publication of The Lord of the Rings in 1954-55 has irrevocably established the fantasy genre as we’ve known it since. Today we are witnessing the spectacular rise of “roman-tasy” (a mix of romance and fantasy). Or, to take another example, nonfiction was once the sole purview of academic writing, but roughly since the middle of the 20th century, we’ve seen narrative components increasingly being incorporated into that style of writing. Today, narrative nonfiction, as it is known, is one of the most popular genres there is.

And so, I might have a strong preference for one genre over another, or a pull toward a certain author, but as an informed reader I remain aware of the existence of other genres, styles, authors, and so on. I don’t do this by actively keeping up. I am rather simply exposed to all these books. I see them on bookshelves, I read the backcover of a book that looks nice, or come across the occasional review. Visiting bookstores regularly, seeing the new books coming in, the new releases from a diversity of houses, the store’s displays and highlights, resurfaced backlist titles or classics are all forms of exposure that give us an idea of what’s out there, and over time, this broadens our horizons regarding topics, styles, epochs, author origins and so on. Therefore if I stick to one specific genre, it’s not because I don’t know about the existence of any others, it’s because I’m knowingly choosing this one.

But even if I visit bookstores regularly, poor distribution means that I won’t be exposed to a diversity of titles (or, find them for that matter, even if I’m actively looking for a specific one). In my color metaphor, poor distribution is like imposing a colorblind person’s vision on the whole population. In this case, no amount of publications about books can make a real difference.

Broadly speaking, censorship is an intentional and ideologically-driven prohibition of access to books, while poor distribution is a structural one. Yet, even if unintentional, it results in the same effect. And therefore, both of these things affect our freedom to read.

Being more or less exposed to books creates imbalances amongst people, the same way in which unequal access to education creates immense differences in prospects. There is indeed an interesting co-occurrence between a country’s innovations and its circulation of books: the wider the level of circulation, the higher the level of innovation. Of course such countries also tend to be richer and have higher rates of education. But this isn’t a rule. The Gulf states, for example, are rich countries with high education levels, but are not known for their innovation (at least not yet). Many state-led initiatives testify to the awareness of a lag in innovation, and in a need for it. Incidentally, most Gulf countries, have what would be considered poor levels of book circulation and offer little exposure to their citizens.

In these cases of systemic limitation, people may not even be aware that their freedom to read is hindered. But this doesn’t change the fact that it is. Freedom to read only exists when people are given not just the opportunity to read, but the opportunity to choose what they want to read. This requires not only access to books, but to information, so that people might have a good awareness of the alternatives available to them.

Independent information

One might think the problem of the lack of physical access to books could be solved by going digital. While this is an interesting and potentially powerful solution, it doesn’t necessarily mean readers are more exposed, as in this case, the problem becomes the abundance of available titles. There is such a glut of books buried in the virtual depths of digital book apps or e-commerce platforms that “browsing” them is nearly impossible, especially that our access to them is entirely dependent on how “discoverable” they are, which means, whether or not, or how often, they are recommended to us by the platform’s personal recommendation engine.

Although it is called “discoverability,” the purpose of the personal recommendation engines (by far the most efficient recommendation tool) is not so much to inform you about other books out there, but rather to inform you about other books out there that you are likely to consume based on your previous consumption patterns. The engines are designed to keep you in the safe space of your own tried and tested preferences. In essence, these algorithms do the opposite of enabling discovery. They rather ensure that readers will rarely chance upon something too new — too far from their assumed interests. And while the process of discovery itself doesn’t necessarily mean we will choose differently — though it might shape the way we read — it enables us to choose knowingly, with our preferences contextualized against a much wider backdrop.

The fast evolution of AI has however already begun to change our experience of receiving recommendations, though we have yet to see what long-term effect this might have. Some platforms have enabled AI agents to act as a bookseller would, recommending books according to what a reader might be looking for. Users input descriptions such as “reads that are cozy and warm,” or “books suitable for an afternoon summer read,” and AI then offers up a number of suitable titles. The only problem is that the prompt still issues from the readers, who are naturally relying on what they already know or have already experienced in order to create the prompt. And of course, AI is commercially driven. Readers might get a greater sense of agency, but they in fact remain limited to their own “user profile.”

Once again, this calls into question the readers’ freedom of choice when it comes to selecting books. Thus, even this digital solution to the problem of broken distribution chains results in a dearth of information about available titles. And so it seems that in order to have truly useful information, it needs to be made available through more independent means, that are less commercial.

Truth and diversity

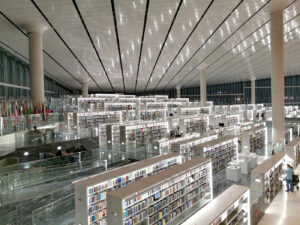

So, does freedom to read mean having as many books as possible available in a physical space — where arguably no commercially driven personal recommendation engines operate? Would readers then be able to gather enough information about alternatives, make informed decisions, and thus consciously access whatever they want?

Not exactly. We still run into similar challenges. The problem with this supermarket approach is the quantity of information we can process as human beings. Be it on digital platforms or in bookshops, only a small, graspable quantity of books can be attended to at any given time, and we need guidance to narrow down what information might be relevant to us. In large, physical bookstores, offerings are curated in various ways, particularly through the placement of books in the store. Whether a book is displayed in the front window, or on the front or back table, whether the book on the shelf shows its cover to the reader instead of its edge, as well as the length of time — a week, two weeks, a month — that a book might be displayed are all differently-priced options that publishers accept to pay to make sure their books stand out.

There is no doubt that readers need guidance. It is the nature of the guidance that is key. Truthfully curated bookstores will make recommendations based on their vision of why a book matters, and on their staff’s sincere preferences. It is neither the commercial value of the prime spot in the store, nor the reader-centric preferences that drive these suggestions. The curation in this case is not so much personalized as it is personable, based on a love of books and a passion for reading.

As in many other things, we tend to defer to the experts. And booksellers are experts not because they know better what makes a book interesting, or because their opinions mirror ours. It’s because by nature of their job they are better informed about the books that are out there. Over time, readers might come to prefer one bookstore over another because they’ve learned to trust a certain bookstore’s recommendations, and to like their vision and tastes.

Good information about books is not unbiased information: book curation is naturally biased. This is in fact what the reader seeks. Readers want to know what some specific bookstores flag as noteworthy – as readers tend to visit more than one, thereby engaging with a diversity of trustworthy sources of information.

Freedom to publish

I mentioned state censorship in the beginning of this piece, but states, in fact, no longer hold the monopoly on censorship. While some of the reasons behind state censorship might be obscure, its most consistent red lines are well known. In most Arab states, these commandments are:

Thou shalt not criticize the State

Thou shalt not disrespect Religion

Thou shalt not indulge in explicit Sexual Content (especially when it is between people of the same sex).

The newest censorship apparatus, however, is the social media mob. The mob is a totally different beast, as there is no way to really tell what might trigger its wrath. It is a mostly unpredictable, often misinformed mass of people. However, once the mob gets wind of a book it deems problematic, bashing it on social media and advocating for its boycott, the damage can be quite serious.

This new owner of the power to censor reveals deep changes in how we relate to books. The romantic view on censorship is one that involves a noble fight for the cause of freedom of speech. Countless courageous authors, thinkers, and journalists have faced imprisonment or even death — an ongoing situation that continues as I write these words. They stand alone in the face of the state, risking their lives to cross boundaries in order to remain true to their beliefs. It is clear who is in the right, and who is in the wrong. In contrast, when it comes to mob censorship, things get so polarized that the notion of right and wrong becomes blurred, almost obsolete, as fewer values are shared.

While censorship by the mob involves neither prison nor death sentence, it is still quite terrifying. Apart from the psychological damage the public shaming sometimes causes, the real impact is economic: The book, the author, the publisher, or all of the above, get punished with a boycott for defying the mob. As a result, their reputations (which also hold important financial value) take a hit as well.

What the rise of this new censoring force reveals is that books have become more of a commodity than ever before. Books are increasingly seen as consumable products. It is now common for print-first publishers to “enhance editorial decisions” with data, ultimately selecting manuscripts on the basis of spreadsheets filled with performance metrics rather than based on the perceived inherent quality of a book, or on the editor’s passionate interest. Even the change of vocabulary — where the act of “reading books” has been interchangeably used with “consuming content” starting in the 2000s — is an eloquent illustration of this fact. In mainstream publishing, the general viewpoint is that books only deserve to be defended if they prove consumable to as wide an audience as possible. While this thankfully isn’t the case for all published books, we can safely say that as with everything else, consumerism is shaping our relationship to books in important ways.

In the countries that are today the leaders of publishing, this is in fact where the real damage to our freedom to read is done. The view of books as commodities rather than art is what pushes e-commerce and digital platforms to design recommendation engines in the ways that they do; it is what gives the mob the power it currently has; and perhaps most importantly, it is what flattens the books being published. Editors are pressured to produce more books, cheaper and faster; books that have the most potential to sell. As a result, with publishers all trying to reproduce the latest commercial phenomenon, so many mainstream books seem thoroughly uniform, challenging neither our precepts, tastes, or ways of seeing the world. When our reading choices are increasingly shaped by market forces, the very meaning of the freedom to read becomes a serious question—no longer something we can take for granted.