What is the work of the writer when sci-fi is already being exploited to further the most reactionary political ends?

Egypt +100: Stories from a Century after Tahrir, edited by Ahmed Naji

Comma Press

ISBN 9781912697700

Of all literary genres, speculative fiction might be one of the most politically amphibious. Would a story predicting the ascent of AI and the superseding of human labor be read as a cautionary tale, or an invitation to entrench techno-capitalist regimes in the present?

Depicting oppression, obviously, is not the same as endorsing it. Think of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, a foundational work in Anglophone sci-fi, and its inauguration of a “feminist dystopian” canon: the novel managed to maintain a sufficient critical distance from, and ultimately excoriate, the horrors of a fundamentalist misogynistic state. Amplified alike by its TV adaptation in 2016 and by the overturning of Roe v Wade in 2022, Atwood’s warning came to seem eerily prescient — all the more timely and deserving of being heeded, as life appeared to imitate or even exceed art in sheer ghastliness.

But the fragile boundary between critique and espousal, seemingly subject to the vicissitudes of context and readership, always threatens to collapse. Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem, an internationally bestselling trilogy translated from the Chinese, furnishes a revealing case study. By painting what Chenchen Zhang terms “an interstellar version of neorealist IR theory,” Liu’s series appears to have promulgated, or at least propped up, social Darwinist fears of civilizational extinction in the real world; his fictional cosmology has been weaponized as fodder by technological determinists to feed a rapidly metastasizing vision of fascist authoritarianism. How much did authorial intention matter in these two instances? Do the afterlives of speculative fiction ultimately hinge on the kind of reader that laps it up? How might we approach sci-fi more expansively, if not as a prescription that merely confirms our worldviews and prejudices?

This constellation of questions arches over Egypt +100: Stories from a Century after Tahrir. The collection constitutes the latest addition to Comma Press’s vital Futures Past series, whose worthy ambition to pluralize sci-fi beyond the West complements its cohesive concept. Each volume is organized along the fraught contours of national collectivity and sovereignty, specially commissioning contributors to imagine how their people might be faring a century after an earth-shattering, and often cataclysmic, event. For past candidates Palestine and Iraq, the chosen turning points were, respectively, the Nakba of 1948 and the US-led invasion of 2003. Egypt +100’s watershed is the January Revolution of 2011 — closest to us in memory, and therefore projected furthest into the future.

Appropriately, the collection is edited by Ahmed Naji, an Egyptian journalist and writer who was incarcerated in 2016 for the charge of “violating public decency” with his novel Using Life, and who now lives in exile in the United States. In his Introduction, he expresses the challenge of feeling out where the contours of “science” and “fiction” might lie in reality, since Arab dictators themselves evince an “almost unlimited appetite for the aesthetics of science fiction.” Think of Saudi Arabia’s Neom and the Line, and Egypt’s New Administrative Capital. What is the work of the writer when sci-fi is already being exploited to further the most reactionary political ends? More than anyone, Naji — through his diasporic vantage and his brutal subjection to a repressive regime — is poised to re-examine our assumptions of the genre, and to present a tentative prospectus for its potential.

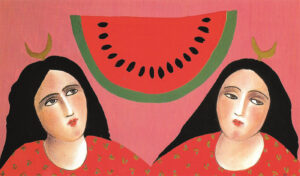

Given the increasing visibility of Arabfuturism as a nascent cultural movement, the time is ripe for such an anthology. Witness, for instance, the ongoing Arabofuturs exhibition at Paris’s Institut du Monde Arabe. It showcases an excellently curated selection of contemporary art from the SWANA region, ranging across such disparate themes as archaeology, posthumanist cyborgs, organic non-anthropocentric worlds, and rabid consumerism. Taking cues from Afrofuturism — especially Kodwo Eshun’s reconsideration of its politics as an “intervention within the dimension of the predictive, the projected, the proleptic” — the incipient style of Arabfuturism similarly hopes to defy and rescript Orientalist prognoses of impoverishment, catastrophe, and permanent war. Perhaps it is this explicit politicization that distinguishes Arabfuturism from earlier incarnations of speculative fiction in the Arab world — a genealogy that Naji also historicizes and insightfully traces for Egyptian literature in his prefatory notes.

Especially now, against the interminable genocide that the Israeli death machine continues to inflict on Palestinian bodies, revolution emerges as an urgent chronotope. Where do revolutionary energies and affects go after they are brutally extinguished? Stitching together the stories in Egypt +100 most directly is each writer’s anticipation of Tahrir’s legacy — the shape its memory will take, and how it might surge again into the topsoil of consciousness if it is momentarily repressed into oblivion. Yasmine El Rashidi’s “Oral History of a Past, Obsolete and Forgotten,” the sole entry written originally in English, confronts history’s attenuation head-on through the ascendance of a virtual realm known as the “verse.” In it, all human interactions and operations have been rendered incorporeal. The idea of a gathering “in the flesh, on the streets,” so foreign to the narrator’s experience, arrives only as an orally transmitted tale from her grandmother. Whereas the nascent hope of the 2011 Revolution meant “everything” to that generation, their descendants lost touch with its promises, assimilated all too cleanly into a vacant, AI-dominated world.

To erase the past might be to maim a people politically. These are arguments for the preservation of archives, tributes to the importance of intergenerational education. Nora Nagi’s “Unicorn2512” (translated by Mayada Ibrahim) likewise presents a metaverse in which public squares are outlawed even digitally, pre-emptively stamping out the possibility of insurrection. Its protagonist, known only by her on-screen alias, is struck one day by the desire to write a story and “cut language open.” Piecing words together turns out to be a radical act when most of them have been forbidden; she feels her voice fading, her pixelated persona dissolving as she reads her composition out loud. But her death sparks new assemblies of people who take turns reciting her writing. In a flare of optimism rare for the collection, Nagi’s story ends with the street turning “suddenly into a public square,” coalescing around its martyr.

Apart from technologized hegemony, Egypt +100’s authors equally give airtime to the inevitability of ecological disaster, and ensuing aggravations of the rich/poor divide.

Algorithmic supremacy reaches an apogee in Ahmed Wael’s “The Solitude of Prince Boudi” (translated by Raphael Cohen), which features an omnipotent “digital cloud” governing humanity. Yet this is a premise that the story wears thinly, granting it room for unexpected twists and ricochets. One of the anthology’s stranger contributions, Wael’s hilarious piece unwinds conspiracy theories of illegitimacy and disavowed paternity; the eponymous Boudi resolutely constructs his identity on the belief that he is the heir to King Farouk’s throne. Meeting with ridicule from officers, he finds compensation in marriage to Katerina, a shrewd Russian woman gifted with foresight. She quickly intuits the entertainment value of his delusions and consecrates them in a novel, soon hailed as a masterpiece. Storytelling, fashioned into currency in the guise of love, awaits the next gullible successor to take its bait.

Apart from technologized hegemony, Egypt +100’s authors equally give airtime to the inevitability of ecological disaster, and ensuing aggravations of the rich/poor divide. Michel Hanna’s privileged protagonist in “Encounter with the White Rabbit” (translated by Mohammed Ghalayini), housed within the gated Capital, has hardly ever ventured into the migrant-overrun Cairo and surrounding areas. He leaves only in desperation, to seek out cancer medication for his dying wife. Heba Khamis’s “Drowning” (translated by Maisa Almanasreh) spotlights a nightmarish vision of Cairo as a Venice-like tourist destination for the wealthy, while the sea levels’ incessant rising force the high-rises’ more penurious inhabitants to vacate their residences. Animated by undead spirits and prophecy, the waters mysteriously appear dyed the shade of blood. Mansoura Ez-Eldin’s “The Wilderness Facilities” (translated by Paul Starkey) visualizes an Egypt that has consigned its rebels to the margins and razed their villages to ruins. Architecture, “worshipped” as a harbinger of “civilization,” also functions as a tool of carceral control.

Across these intersecting anxieties, some of the writers reveal a concern with the ethics of reproduction as the planet burns. Mohamed Kheir’s “The Mistake” (translated by Andrew Leder) examines childlessness as a form of dissidence, while Camellia Hussein’s “Mama” (translated by Basma Ghalayini) imagines a mother who, like Sethe in Toni Morrison’s Beloved, must kill her child to prevent it from belonging to the “bosom of the state” and being literally remade in the dictatorial leader’s image.

Ahmed Naji’s “The Tanta White People Museum” (translated by Rana Asfour) represents another highlight. His hysterical satire relies on a total inversion of racialized hierarchies, envisaging a Global North eroded from within by its intensifying Nazism and denial of climate change.

While the above pieces all engage with relatively well-defined capital-letter issues, the most enduring stories will likely be the ones that elude categorization. They stand out for sublimating their preoccupations into scenes and plotlines that feel like extracts from longer works, glimpses into whole pulsating universes. I found myself wildly amused by well-known satirical columnist Belal Fadl’s “God Only Knows” (translated by Raph Cormack), voiced by a mufti who has inherited his grandfather’s and father’s vocation of issuing fatwas to guide Muslims in the insurmountable conundrums of everyday life. More a record of family achievements than a forward-moving chronicle, the narrator trots out questions around the use of virtual-reality technologies in resolving marital disputes and the permissibility of same-sex marriage when global drought and famine endanger reproductive futurity. Fatwas serve as a bulwark reassuring the masses amidst volatile epochal shifts; the long-suffering mufti narrator laments feeling “like a talisman instead of a person.”

Ahmed Naji’s “The Tanta White People Museum” (translated by Rana Asfour) represents another highlight. His hysterical satire relies on a total inversion of racialized hierarchies, envisaging a Global North eroded from within by its intensifying Nazism and denial of climate change. Meanwhile, the Arab world gains in unity and economic porousness. A freak epidemic precipitates the development of a vaccine that cures at the cost of darkening one’s skin — a wink, perhaps, at George Schuyler’s Black No More, which presents the inverse scenario. Predictably, the white people resist inoculation, “regarding it as an infringement on their cultural specificity.” They are soon all but wiped out, with whiteness becoming a marginal identity position, “rewritten by the dominant Islamic powers.” The elaborate, tongue-in-cheek set-up forms the backdrop to the main chain of events, where the founder of a “white people museum” must reckon with the prospect of terrorist attacks.

Out of everything in Egypt +100, Ahmed El-Fakharany’s “Everything is Great in Rome” (translated by Robin Moger) bowled me over most entirely. Within its vivid, throbbing pages, Tahrir Square is remade as a Roman colosseum, and murderous gladiatorial prizefights provide the population with much-needed diversion. In the background lurks the enigmatic five-decade disappearance of a leader known only as Our Lord, about whom floats the burnished aura of sainthood. When the always-victorious fighter Abdel Moula is instructed to stage his own loss in a match against Our Lord, bodily decrepitude and messianic myth must wage a fight to the finish — and death begins to look a lot like eternal life.

Not all the entries in the anthology are conceived with the same depth and suppleness; nor do they need to be. Some work as thought experiments, omens extrapolated from a present already teetering on unliveability. Others thrive on their absurdity, striving to elicit a chortle. Whether morose or detached, fervent or ironic, all the writers seem united by their longing to wrest Egypt out of its post-revolutionary gloom — the disillusionment, neoliberalism, and foreclosure of futurity into which it plunges ever more deeply.

And yet nothing is thus far irrevocable, the contributors insist. As the protagonist of Hanna’s “Encounter” wonders, seeing what used to be Tahrir Square engulfed beneath a deluge, “The question was: what happened to all that rage.” Naji, the collection’s marvelous editor, convincingly points in his Introduction to the non-linearity of grammatical tense in Arabic as an orienting trope for the emergent domain of Arabfuturism. In El Fakharany’s fiction, too, “marvels” and “science-fiction” jockey in tight proximity with traces of “the distant past.” If time can be so elastic, will we, as readers, see a way beyond this ouroboros, through to the rage they once harbored — so that it may one day quicken back into luminous life?