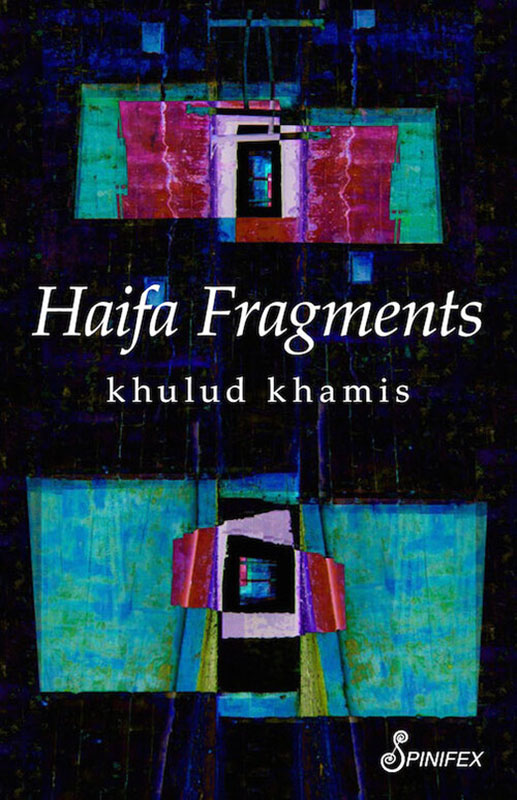

In this excerpt from khulud khamis’ novel Haifa Fragments, jewellery designer Maisoon seeks “an ordinary extraordinary life,” which isn’t easy for a tradition defying peace activist, and Palestinian citizen of Israel, who refuses to be crushed by the feeling of being an unwelcome guest in the land of her ancestors…Frustrated by the apathy of her boyfriend and her father, enamoured with a Palestinian woman from the Occupied Territories, Maisoon must determine her own path.

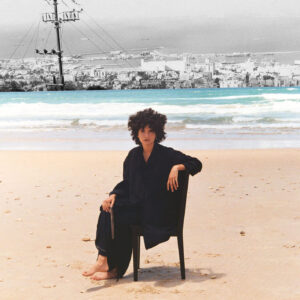

khulud khamis

At the beginning of the following week, Maisoon has some finished pieces she needs to take to the boutique and asks Christina if she would like to join her. “We won’t be long. After that we can go back to Wadi Salib if you want.”

They take the Carmelit up to the Carmel, “the shortest underground in the world,” Maisoon laughs as they get off several minutes later at the last stop. They spend about an hour at the boutique, and while Maisoon is busy rearranging the jewellery, Amalia and Christina talk — mainly Christina answering Amalia’s questions about her experiences and first impressions of the West Bank. When they emerge from the boutique, the sun is halfway up the sky. They walk the short distance to the bus station in silence.

“Let’s take this bus, it goes a longer way, but you’ll get to see some new parts of Haifa,” Maisoon points at bus number 5. They get on and sit close to the back, Christina by the window.

The doors close and they begin to descend from the Carmel — a winding road connecting mountain and sea, called Derech Hayam in Hebrew — the Sea Road. As they descend the mountain, Christina notices that the houses become less grand, the streets are not as clean and proud. She imagines the residents from on high looking down in disdain at the lower parts of town — Hadar HaCarmel, Wadi Nisnas, Halisa, Kiryat Shprintsak, Kiryat Eliezer.

“So, this story your grandmother told you … about what happened to her in 1948 … did it make a change in how you see things today? I mean, did it have a significant effect on your life?”

“You know, I never thought about it like that. Of course it affected me but not in any particular way. I mean, I can’t isolate this or another experience and point to a clear effect on my life. It’s a package deal, you see. Every one of them adds to the ones before it. And what are we made of, if not our past?”

The bus continues down the winding road, and towards the end reaches a bus station with about seven or eight soldier-boys standing around. It stops for about a minute and a half — which seems too long to Christina, who is sitting at the window, only glass separating the men from her. Weapons always make her edgy, especially when slung over the shoulders of boys. One is smoking, letting failed rings of smoke out of his mouth. The other is standing talking to him, and at one point shoves his hand down his pants to adjust his penis and scratch around it. The machine gun sways slightly with his exertions. These guns aren’t like the ones she’s seen before on the streets of Haifa and the West Bank. They seem heavier, thicker. Or maybe they’re the same and only look more threatening because she’s sitting next to a Palestinian woman who crosses that forbidden line every now and then. What if one of them gets on the bus and decides to sit opposite her, the machine gun pointing in her direction? What if he hears Maisoon’s accent or, worse even, what if he hears Maisoon saying something not to his liking? She sighs with relief when the bus takes off without any of the soldier-boys getting on. Then, a second sigh on account of her blonde hair and fair complexion.

A couple, one of them holding onto a shopping cart, gets off at the next station. An old man walks by, holding a transistor radio to his ear, the antenna sticking out. The bus continues. Now they cross a clear boundary, leaving Kiryat Shprintsak behind with its dilapidated, colorless houses and enter Wadi El-Jmal — Ein Hayam in Hebrew.

“The Arabic name means the Valley of Camels while the Hebrew means the Eye of the Sea.” Maisoon’s commentary picks up, “The Arabic name comes from the area being historically a resting point for camel convoys coming from the North — Akka and the Sham, on their way to Jaffa, Gaza and then Egypt.”

The bus stops, a young Arab woman gets on with two small girls. Nobody gets off. Maisoon motions towards the mother, “Look how calm she is? It wasn’t like this some years ago. I remember after a bombing of a bus that I used to take regularly, I … I couldn’t get on a bus anymore. Everybody was taking taxis.” She lowered her voice. “I took a taxi once but never again. Two men sitting in the back were discussing the security situation and how Arabs are all traitors and can’t be trusted. Anyway, right in the middle of this, my mobile rings. I panic. It is Tayseer’s number. I hesitate before answering. Then I hit the green button and my ‘aloo’ comes out sounding very Arabic … like I wanted to provoke … I didn’t let my fear or panic show. I will never forget the faces of the two men when they realized I was an Arab. The enemy, sitting right there with them in that crammed space. After that, for months I would walk everywhere. If I needed to go someplace far, I’d ask my father or Tayseer to drive me, or I would borrow my father’s car.”

The architectural scenery is breathtaking. Christina concentrates on the old stone houses. Greenery gone wild. Other houses are newer, but built in ways that are reminders of the past.

“But you can’t say this is how it was for every Palestinian after a bus had been bombed. This is how it was for me. And I still can’t get into a taxi. But this woman — look at her. Maybe she took the bus the day after a bombing. Maybe she didn’t. Maybe a relative of hers was on a bus that was bombed and it has taken her years to get over the panic, maybe she’s forced herself to get on the bus every day and that’s how she’s gotten over it. This is how it is around here, this is how we live …” Maisoon shrugs.

A few minutes later, they are out of the residential neighborhoods and on the main Sea Road, passing the National Maritime Museum of Haifa — with two warships exhibited in front of it, an unnecessary reminder of wars. After that, they’re in the ‘business’ sector of downtown — car agencies, falafel and shawarma places, metalwork workshops. All of this among scattered unoccupied houses, their owners expelled in 1948.

They get off the bus one stop before Kiryat Ha-Memshala — the Government district, with its ugly glass buildings and lawyers’ offices that are fast encroaching on Wadi Salib until one day, no Wadi Salib will remain. It’s a short walk to the souk. At least we’re not at the very bottom of this mountain, Maisoon thinks as they walk up Mar Youhanna alley.