Fadi Kattan

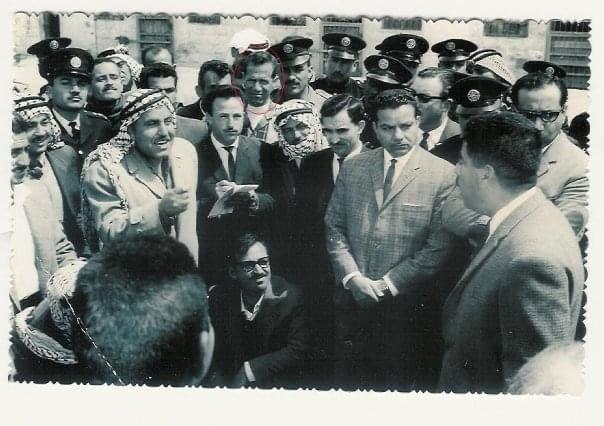

When I think about food and incarceration, the stories of the late Palestinian community leader, Daoud Iriqat immediately come to mind. He was always a lesson in optimism and perseverance, carrying his political ideals high and proud through the shifting sands of our regional history.

Spending long years in prison and then more in exile, food represented his sense of identity as well as his intense longing for home. However, at times his pursuit of food behind bars was itself all-consuming; it was a practical necessity, a matter of life and death.

Daoud’s mother was from an old Jerusalemite family while his father was a landowner in Abu Dis, so he grew up between the city and the village. As a young man, he was religious and would go to pray at Al Aqsa Mosque. Because his friends and peers were not religious, they would often taunt him, calling him “the Sheikh”— a nickname that followed him through life. He liked to joke that his parents had sent him to Egypt to study theology at Al Azhar and had expected him to come back a scholar, but when he got off the bus, he was carrying an oud and singing.

When he would walk around Jerusalem, Daoud’s elder brother, Ahmad, who was a teacher and an intellectual, would task him with distributing the Communist party’s newspaper. He started reading the paper and discussing it with his brother. Thus, he shaped his own Communist Leninist ideology.

Daoud joined the Jordanian Communist Party in the 1940s and after the party split, stayed on in what became the Palestinian Communist Party.

He famously used to tell his family a phrase that encompassed his entire relationship with food: “I hate the empty plate!” It was a refrain pinched from his mother, who like so many Palestinian mothers was an accomplished cook and generous host.

Daoud’s memories of food were dominated by his mother’s sumptuous mahshi, stuffed vegetables. In Palestine, Jerusalemites are well-known for the different mahshi they prepare: zuccini, eggplant, vine leaves, cabbage leaves and so many more. However, Daoud’s favorite meal was mansaf, that hearty dish shared in Jordanian and Palestinian traditions — melt-in-the-mouth lamb in a tangy fermented yoghurt served with rice.

But mansaf was something that Daoud could only dream of after he was imprisoned in Jordan’s Jafr jail in 1957. He was condemned to 16 years: one for participating in a demonstration and 15 for being a member of the Communist party.

Imagine how it must have felt to be in a prison in the harsh, barren desert, for a man who thrived on culture, music and eating well.

Very quickly, as Daoud would recount, he and the other prisoners focused on what they saw as the necessities of life: education, food and alcohol.

They organized themselves to teach classes of party politics, languages and music. For musical performances, Daoud dried the shell of a squash and made an oud out of it.

However, improvements in food required more imagination and hard work. The rations the prisoners were given were low in protein and iron, and they had begun to feel the deficiencies. This motivated them to carry out what they called “the chicken operation.”

A driver came regularly from Amman with stocks for the jail and the inmates managed to pass him some money to buy things for them. They ordered fertilized chicken eggs and then set about building egg hatchers with cardboard and other scrap materials, anything they could lay their hands on. Finally, when 28 eggs arrived, Daoud and his comrades attended to them on a relay system. They were elated when these hatched into 27 healthy chicks.

Meanwhile, an agricultural engineer who — conveniently — was in jail with Daoud had managed to grow fasouliya, green beans, and a few other vegetables.

As the prisoners had no access to utensils, oils or spices, they improvised. They used any metal tin to soft boil eggs while the chicken meat was often boiled into a broth and eaten. When any fasouliya had grown, they would celebrate with a delicious fasouliya and chicken soup.

Then came the great setback for the prisoners: what was known as Al Maraket Al Jaj, the Battle of the Chicken. The prison warden had witnessed the great success of the poultry farm and most probably getting no fresh meat himself, demanded a chicken from the inmates. After a meeting, the prisoners collectively decided to oppose the move which they saw as pillage or extortion. Daoud would recall how he tried to reason with them — reminding them that they were ultimately powerless — but it was to no avail.

When the jailer was told he could not have his chicken, he raided the farm with his guards and confiscated all the birds and the prisoners’ books. To add insult to injury, he broke Daoud’s oud.

Not to be deterred, the prisoners restarted their chicken project from scratch. It was an endeavor that continued until they were released.

Despite all the tremendous creativity and efforts of the jailed men, alcohol was always much more difficult. On only one occasion, after a long, drawn-out process did they ever manage to distill one bottle of an alcoholic drink. Daoud would call it – one imagines euphemistically – arak.

He always remembered the heady party the prisoners had, fueled by that single bottle with the sound of his new oud echoing across the vast desert late into the night.

Freedom finally came in 1965, when the late King Hussein of Jordan issued a pardon for the Communists of Jafr prison. All of the comrades were allowed to return home.

For Daoud that meant moving to Jericho to be with his family and when he arrived back it was clear how they would celebrate: with lashings of the mansaf he had so desperately missed.

However, freedom did not last.

Less than a decade later, in 1974, Daoud was arrested once again, this time from his home in Jericho by the Israeli forces. He was to be punished for having signed the petition recognizing the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) as the sole and unique representative of the Palestinian people.

But instead of imprisoning Daoud, the Israeli soldiers forced him across the Lebanese border, sending him into exile. His provisions – which he had at first refused – were only a sandwich and an apple.

After some time, Daoud made it to Beirut. A year later, he settled in Damascus. Amazingly, in Syria, he found ways to get sent some of the distinctive flavors of Palestine: salty Nabulsi cheese dotted with nigella seeds, pungent zaatar and even fresh guava. But throughout his exile, he would complain of missing the huge, juicy pomelo grapefruit from his garden in Jericho.

Daoud’s second homecoming was not until 1993. Once again, he was welcomed back with lovingly-prepared mansaf.

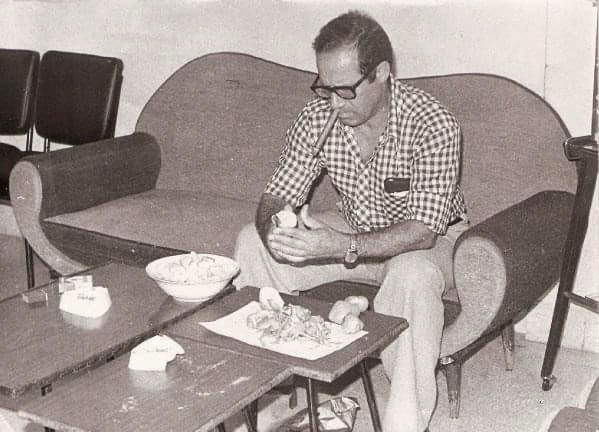

Until his untimely death last year, the large table on the Sheikh’s terrace in Jericho was always a place to delight his guests with his favorite foods — and to serve up food for thought. His belief in humanism, universality, the equal division of wealth between citizens and between countries, his staunch fight for critical thinking and education always endured.

His morning ritual was a sacrosanct time when he would listen to the radio and run an ongoing commentary with his lashing tongue while sipping his Arabic coffee.

But Daoud’s gatherings always revolved around lavish meals; he believed in the power of delicious tastes and flavors to bring people together. It was always an honor to be invited to his home, but the greatest honor came if he really liked you. Then, it would be your turn to be treated to mansaf!