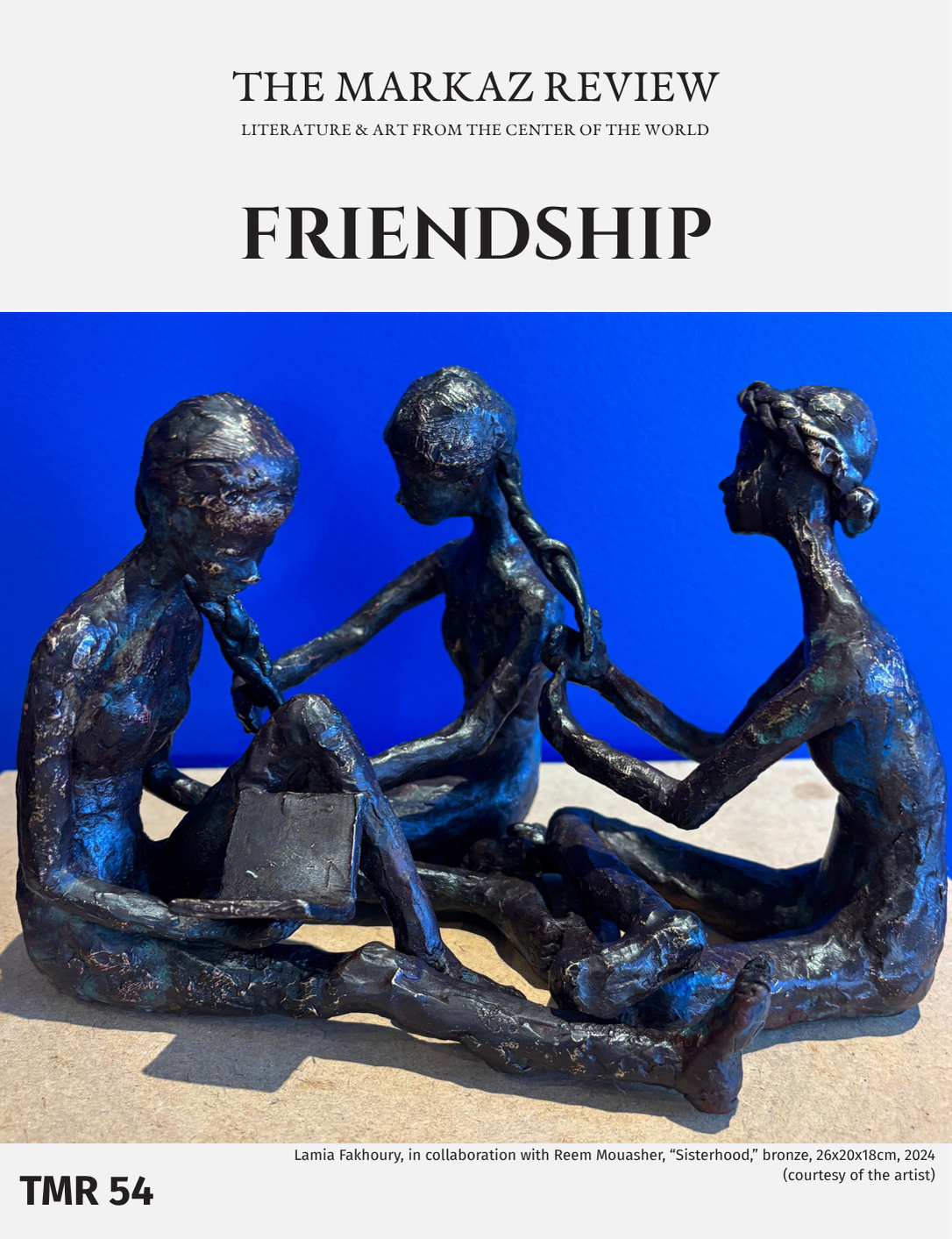

The re-release of a long out-of-print poetry collection and previously forgotten movie powerfully assert Palestinian resistance and solidarity. As these amass new contexts and comrades, what do they teach us about gathering and fighting together?

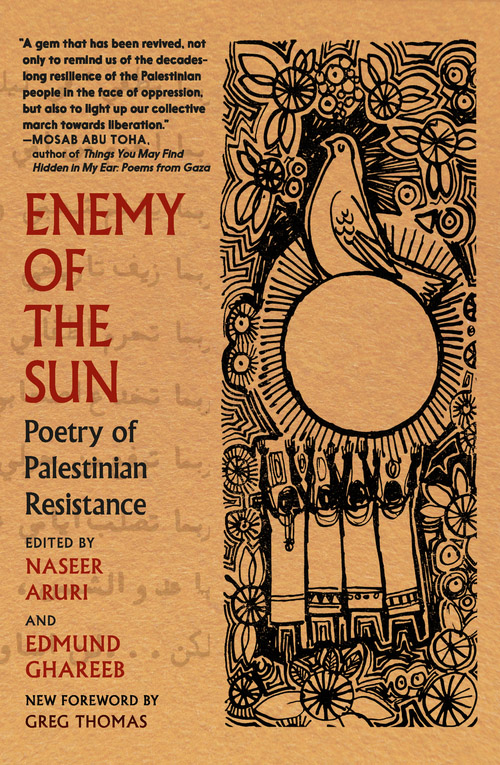

Enemy of the Sun: Poetry of Palestinian Resistance, edited by Edmund Ghareeb and Naseer Aruri

Seven Stories Press 2025

ISBN 9781644214558

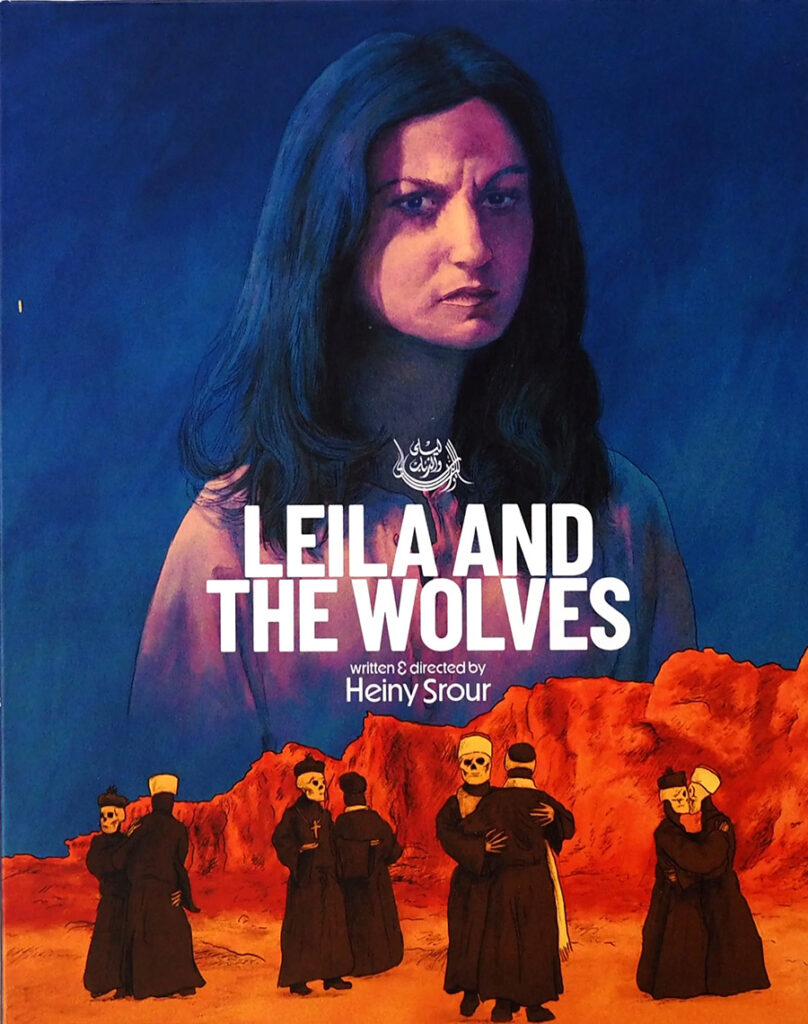

Leila and the Wolves, a film by Heiny Srour

1984 re-release on Blu-Ray 2025

In 1971, the Black Panther Field Marshal George Jackson (1941–1971) was murdered during an escape attempt at San Quentin Prison. Found among his extensive prison library was a handwritten poem entitled “Enemy of the Sun.” Minus a byline, the poem was presumed to be Jackson’s and circulated under that authorship for years after. It was only once the scholar Greg Thomas reviewed Jackson’s full catalogue that the actual provenance was discovered. “Enemy of the Sun” was written by Palestinian poet Sameeh Al-Qassem (1939–2014) and included in a 1970 volume of translated Palestinian poetry first published by the activist bookstore Drum & Spear.

That volume has been newly released in September as Enemy of the Sun: Poetry of Palestinian Resistance. The “magical mistake of revolutionary solidarity and kinship” that turned “a classic poem from Palestine [into] a black poem from Black America” is the narrative that propels Thomas’s preface to the new edition. Jackson, Thomas reasons, must have resonated with the poem enough to transcribe it, to reproduce it using the only methods at his disposal so that it could reach other incarcerated freedom fighters. That the poem was mistaken for his own is not a failure of citation but rather a deeply truthful illustration of solidarity in action.

Some texts, particularly those committed to revolution and resistance, seem designed to travel. As they move across geographies and temporalities, they accumulate audiences bolstered by the notion that their particular struggle does not exist in isolation. There is conviction, inspiration, and strategy to be found alongside those reaching for words an ocean or generation away. “No practice of ‘book worship,’” Greg Thomas explains that the library of “Comrade George… was a partial bibliography of his praxis and revolutionary critical engagements.” The gathering of texts is a way of enacting solidarity and comradeship; by reading alongside, the struggles of each become the struggles of all.

Enemy of the Sun is one of two recently re-released cultural productions championing creative articulations of Palestinian solidarity. The other, Heiny Srour’s brilliant 1984 debut feature Leila and the Wolves, is now available through the Criterion Collection and is soon to be released on Blu-ray. Since March, it has been circulating through North America at a series of screenings at venues as large as BAM and as small as a non-profit art studio in Richmond, Virginia, where I had the opportunity to see it on the big screen with an audience.

They wrestle with the legacy of the Holocaust, pointing to the ways that deep trauma, loss, and fear have warped into a violent colonialism.

The two pieces share more than their recent re-introduction to audiences hungry for their revolutionary messages. Both approach time and context fluidly, relying on a polyphony of voices. They are interested in the kinds of affinities that we can draw across historical and social moments, not with the goal of collapsing specific contexts but rather of harnessing the power and lessons learned from one movement into another. Enemy of the Sun editor Edmund Ghareeb quotes Audre Lorde in another moment of intercultural solidarity: “Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought.” Through poetry and film, Enemy and Leila remind a new generation of viewers of the revolutionary vocabularies already available to them and empower them to create their own.

“Palestinian you were, and so you shall remain”

Enemy of the Sun is at once a 1970 volume of translated Palestinian poetry, written by Palestinians across the region intimately involved in the work of resistance. It is also a 2025 collection featuring newer voices from Gaza and further afield as it reflects on where the previous contributors’ dreams, fears, and sacrifices have traveled. As a translated edition, it is most invested in pulling the attention of English-language readers toward Palestine. Its contextual materials suggest the desire to equip those newly joining the fight for Palestinian liberation with a robust knowledge of resistance literature; a new introduction from editor Edmund Ghareeb includes a careful mapping of the way Palestinian poetry has intersected with political discourse throughout the 20th century.

Many of the original contributors are now familiar names to even the most casual students of Arabic literature. Poems by Mahmoud Darwish (1941–2008) anchor much of the volume, which begins with the famous “Identity Card.” Fadwa Tuqan (1917–2003) appears as one of the few female voices in the 1970 volume. And Nizar Qabbani (1923–1998), most associated with love poetry, documents his own transition toward resistance:

“Oh my sad Homeland

You have changed me overnight

From a poet of love and longing

To one who writes with a knife.”

Contributors linger on the aftereffects of the Naksa in 1967. They wrestle with the legacy of the Holocaust, pointing to the ways that deep trauma, loss, and fear have warped into a violent colonialism. Their imaginary extends globally, creating comradeship on the page. A section of poems including “On American Indians,” “Thunderbird,” “From the Diary of Johnny Guitar,” “From Vietnam,” and “Patrice Lumumba” are preoccupied with global imperialism, indigenous movements, and the shared experience of a country’s youth conscripted into violence. In “Cuba,” Tawfiq Zayyad (1929–1994) extends greetings and encouragement to a revolutionary movement thousands of miles away:

“The people of my village tell many stories about you.

They tell them proudly – with glowing eyes,

With hearts beaming with joy and jealousy.”

The new edition reintroduces readers to this vibrant history; it also extends the collection by pulling in Palestinian poets who have been documenting the ongoing genocide in Gaza or reflecting on the experience of being Palestinian away from Palestine in the current moment. These new additions paint in excruciating detail the experience of standing in the water queue or sifting through bodies in the aftermath of yet another bombing. They are documenting, calling to action, and reaching for the same global and temporal connections as the poets that came before them.

If Enemy of the Sun’s poetry exists, in Lorde’s words, “to give name to the nameless,” Leila and the Wolves gives face to the faceless, creating a wider archive of revolutionary participation than official documents provide.

As a reader of this powerful collection, my only wish would have been for some more dynamic editorial choices that put the book’s primary concerns and philosophies into action on the page. These might have included more intentional coupling of poems, more context around the poems as they appear, and more developed juxtapositions of poems from the initial volume with the new additions. As it stands currently, almost every poem appears without a byline included. Readers need to return to the table of contents to link the poem back to its poet.

The appearance of most poems without an author’s name included does suggest a kind of aspirational universality. And yet the anonymity of each poem for all but the most determined readers teeters from universality into anonymity in a way that threatens to erase the voices it wants to uplift. It’s a tension in a volume that also provides some of the most masterful contributor notes I’ve ever read; Ruqyah Sweidan has crafted storytelling out of biography, using a seemingly standard section of any anthology to enhance readers’ understanding of how arts and political activism intertwined in the life of each contributor. The question of how much each poem belongs to its individual artist and how much it necessarily becomes part of the collective – often one forced into anonymity through colonial violence and erasure – lingers long after the last page.

This tension is especially prominent because one of the collection’s most effective moments occurs across a few pages where poems are carefully contextualized and juxtaposed. In “To my mother,” the speaker enjoins a beloved parent not to grieve as he participates in dangerous resistance:

“Do not brood

For I shall forget your sad face

In the joy of the struggle,

And the agonies of those eyes

And the size of those wrinkles

I shall forget

When the battle rages

Do not worry

For I have a goal in death.”

In the prophetic lines, the speaker predicts and welcomes his own death. He prepares his mother to accept his loss with the same pride and conviction.

The author of “To my mother” is Kamal Nasser (1924/25–1973), the Gaza-born activist, writer, and editor. On the collection’s following page, readers encounter “My Son Kamal,” a poem written by Nasser’s mother herself following his murder in Beirut in 1973 alongside two other PLO members.

Wadi’a Nasser creates her own intertextuality in mourning her son, echoing back his lines and reaffirming her commitment to the struggle in which he died:

“They shall not weaken me.

With the strength of action

I shall continue to hear your voice see you in every youth

And I shall continue to hear your voice

In the mountain passes shouting:

“We shall remain in spite of the enemy

In death, we shall be resurrected anew

And we shall raise our banner proudly.”

In speaking back to her son’s poetry, Wadi’a Nasser builds a bridge. She also serves as one of the few female voices in the initial anthology, a disparity addressed by increased inclusion of women poets among the new contributors. Nasser’s maternal grief is political action. She connects the loss of her son to the shared love they have for their land and motivates others to continue. She sits alongside the heroines of Heiny Srour’s Leila and the Wolves, which is also invested in locating and lifting up the women who sustain fights for liberation.

For director Srour, Leila and the Wolves is an explicitly feminist project. The protagonist Leila is working at a London gallery on an exhibit of Palestinian resistance photography. As she reviews the curated materials, she is drawn to the absence of women from the visual narrative. This moment acts as a loose frame for the rest of the film, a series of temporally disparate vignettes that laser in on women’s revolutionary work from the British Mandate on.

The actress Nabila Zeitouni, who plays Leila, floats through these scenes in a white dress. Occasionally, she and other actors double as characters within a particular moment so that the women participating in resistance to British occupation become those signing up to fight during the Lebanese Civil War. The rotating cast adds to the dreamlike feel of our journeys across these histories; it also reinforces the way one resistance movement learns from those that came before.

In a particularly gripping scene, the women of a village prepare for a wedding, ululating and cooking and decorating the bride with henna, all the while concealing weaponry and ammunition in their plates of food and baskets. As they take their goods into the mountains and past British soldiers – ostensibly to bring the bride to her husband – they are really smuggling needed goods to the frontlines. The coordination of their collective action plays out with minimal dialogue. As we watch their feet process past the soldiers, viewers are hyper-aware of the stakes if just one bullet slips out from a bowl of rice.

These are the ancestors whose wit and courage shape the tapestry of Leila’s voyage through a resistance history. If Enemy of the Sun’s poetry exists, in Lorde’s words, “to give name to the nameless,” Leila and the Wolves gives face to the faceless, creating a wider archive of revolutionary participation than official documents provide. Releasing the film again now, they are also the matriarchs who call new viewers to the same courage, the same commitment to collective action.

Comrades are to be found in the pages of Enemy of the Sun, on the screen with Leila and the Wolves, and among the audiences drawn to these pieces. In one of the new contributions to Enemy of the Sun, Palestinian-American poet Zeina Azzem describes “history unhinged, taken apart, regrouped,” comparing it to “unrhymed free verse.” In both these texts, history exists in all its fractured parts, and these artists solder it together through new affinities, verses and images that expand our imaginations, and a meaningful call to keep going.