From the tombs of prophets and saints to posters of martyrs from the First Intifada in Nablus and Mahmoud Darwish’s mausoleum in Ramallah, Forgotten is a memoir of the Indigenous habitation in Palestine. It is a presence that has been largely erased by the Israeli occupation. However, the Palestinian Authority also has an “amnesiac attitude” towards heritage, according to Gabriel Polley, no stranger to shrines in Palestine, who follows in the authors’ footsteps.

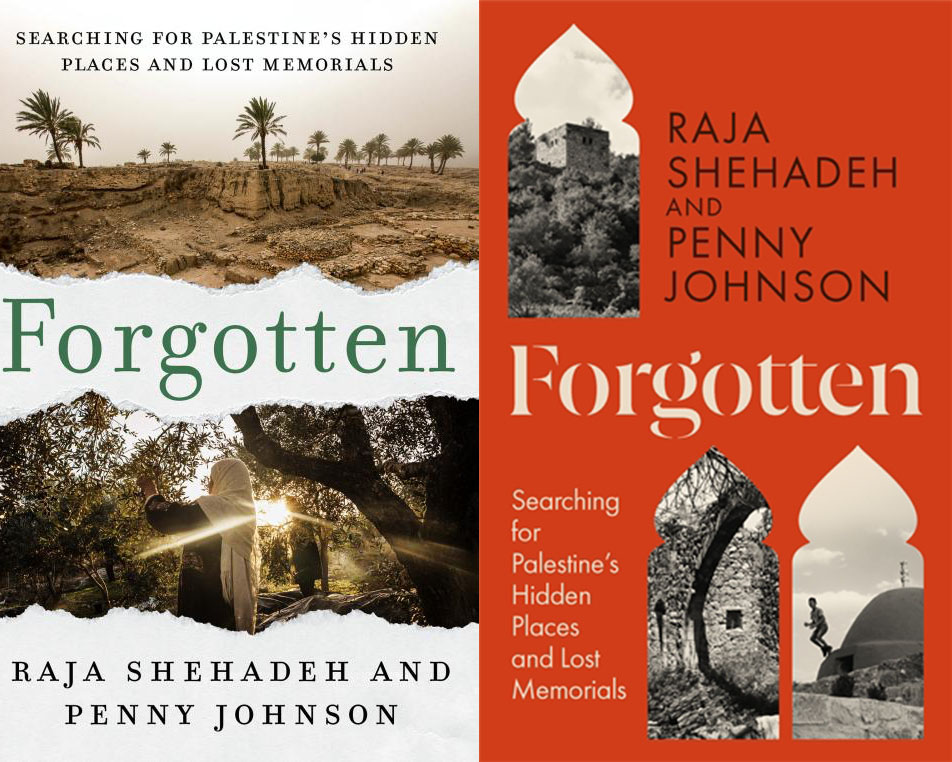

Forgotten: Searching for Palestine’s Hidden Places and Lost Memorials

Travel/history by Raja Shehadeh and Penny Johnson

Other Press 2025

ISBN 9781635424744

Gabriel Polley

Forgotten is an elegiac journey through Palestine’s human landscape. The authors, husband and wife, are Raja Shehadeh, one of the country’s best-known English-language writers and human rights lawyers, and Penny Johnson, a former researcher at Birzeit University and editor of Jerusalem Quarterly. Together they have explored this terrain before, yet in seeking some of Palestine’s most unusual, unknown and uncared-for sites, they provide a fresh account of a land described by so many others.

For centuries, Palestine has been the subject of vast volumes of text. Much of this has not been written by the Indigenous peoples who have called the land their home. For millennia, pilgrims were drawn to the Holy Land, leaving written accounts that were often little more than lists of the sacred sites they visited. In the 19th century, British orientalists produced a discourse of Palestine as terra nullius, awaiting a European empire or settler-colonial movement. More recently, particularly since October 7, 2023, journalists and “experts” have often (mis)represented Palestinians and their cause in ways that leave their subjects feeling abandoned in their moment of greatest need.

Shehadeh and Johnson are aware of this literary baggage, and consciously write back. For instance, on the village of al-Jib, north of Jerusalem, the authors quote the 19th-century American biblical scholar Edward Robinson’s description of al-Jib, as “decidedly the finest part of Palestine that I had yet seen,” and American archaeologist James Pritchard’s more slighting claim of a “self-contained island of the past.” Shehadeh and Johnson’s own mission is to shed more light on a village which is “in today’s common parlance, synonymous with the name of an infamous checkpoint.” They portray a space both physical and temporal, where the Iron Age sits comfortably alongside the present:

Several families and a courting couple from the village sat peacefully under the olive trees, one of them so aged that we gazed at it in delight before we turned and peered down ancient steps to the rock-hewn caves far below, where water was once brought from a spring in the valley.

Such lyrical prose is familiar from Shehadeh’s acclaimed 2007 travelogue Palestinian Walks. But while the older book focuses on Palestine’s natural landscape, Forgotten is devoted to human monuments. The work moves between sites as varied as a wall in Nablus ornamented with posters depicting martyrs from the First Intifada, a monument to an ill-fated Ottoman aviator by Lake Tiberias, and an abandoned Jordanian-era restaurant near the Dead Sea, frequented by marijuana-smoking teens. The authors weave these together in a narrative of unbroken Indigenous inhabitation of the land. Through thematically organized chapters, the history of Palestine over millennia is artfully told.

Several maqam tombs of prophets and saints are visited in Forgotten. For example, in West Jerusalem, the shrine of Nabi Ukkasha, “an Islamic holy man who came to Jerusalem with Caliph Omar in the Islamic Arab conquest of the city in the seventh century,” might alternately be the tomb of Husam al-Din al-Qaymari, a 12th-century commander in Salah al-Din’s army. Today, the tomb is held by ultra-Orthodox Jews as a shrine to the Prophet Benjamin. (A friend told me that one member of the present-day Qaymari family expressed a bitter kind of relief that, in the absence of any protection of Arab and Islamic heritage by Israel, at least someone cared for the upkeep of the tomb.) Shehadeh and Johnson also visit the more contemporary tombs of Palestinian artists, from the hilltop-spanning mausoleum of national poet Mahmoud Darwish in Ramallah, to the modest grave of Rashid Hussein in the poet’s Galilee home village of Musmus, and the unfinished plot of painter and art critic Kamal Boullata in Jerusalem.

While some sites visited in Forgotten have passed into obscurity because of changes in Palestinian society — for decades, few have venerated the saints commemorated by maqamat — others have been willfully erased or neglected. The chief culprit is unmistakably the Israeli occupation. Perhaps most powerfully in their chapter on Manshiya, “the once lively quarter of the Palestinian city of Jaffa near the Mediterranean Sea,” Shehadeh and Johnson show how, since 1948, Israel has worked obsessively to eliminate traces of Indigenous presence. In Manshiya, this even involved evicting the Israeli Jews who lived in the Arab homes when they were demolished in the 1970s, to make way for the empty expanse of Tel Aviv’s Charles Clore Park.

Yet Shehadeh and Johnson do not hold back when Palestinians are complicit in the erasure of their own past. In particular, their ire is directed against the Palestinian Authority (PA) and its embrace of neoliberal capitalism, with an amnesiac attitude towards heritage. This is something the PA has inculcated in some of its citizens. For instance, the authors give special mention to the proprietor of a gas station, built on a khirba (a mound showing traces of ancient habitation) in a Ramallah suburb; having “received a permit with the condition that he did not destroy a Byzantine water reservoir […] He promptly bulldozed the site to five meters below bedrock.” The PA’s official attempts at remembrance are also critiqued. In Qibya, a West Bank village where 77 Palestinians were killed by Israeli soldiers led by Ariel Sharon in 1953, Shehadeh and Johnson depict a “curiously unmoving” new memorial “in the middle of a roundabout,” where a tree had once grown which “would have been a more appropriate commemoration than the artless monument.”

The Gaza genocide, during which so much of Palestine’s heritage has been destroyed (the proportions of which are examined in the Paris exhibition, Trésors Sauvés, 5,000 Ans de Gaza, at the Institut du Monde Arabe through Nov. 2), has illustrated the threat still posed against not only the Palestinians of today, but also what has been left by their ancestors. Forgotten is a valuable record of Palestine, as told by two eloquent and erudite observers. In words which resonate beyond Palestine in a world where heritage is increasingly threatened by conflict and environmental disaster, as well as an amnesia that seemingly inevitably accompanies technological advances, we may join with Shehadeh and Johnson in hoping “that we will continue to pay attention both to what we love and what troubles us.”