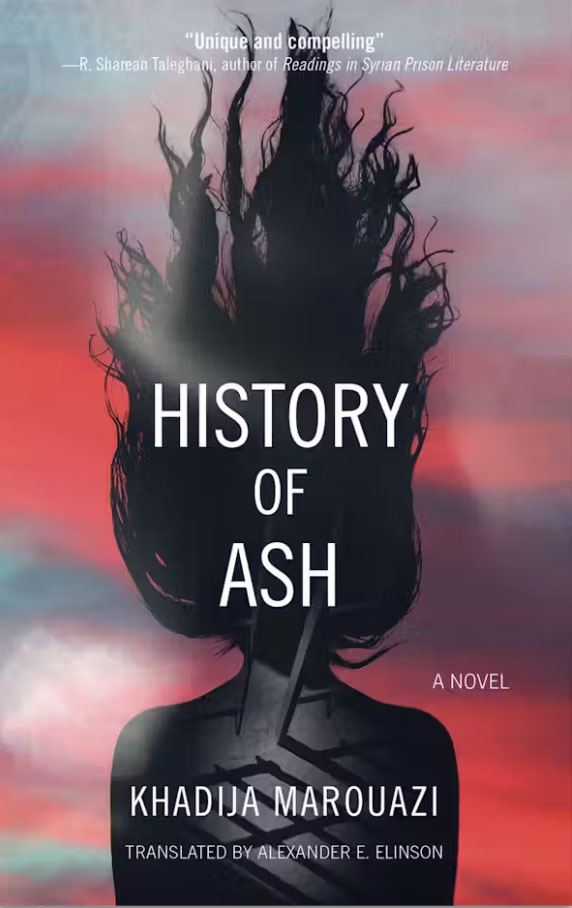

History of Ash is a fictional account narrated by Mouline and Leila, who have been imprisoned for their political activities during the so-called Lead Years of the 1970s and 1980s in Morocco, a period that was characterized by heavy state repression. The excerpt highlights key moments from chapters 14 and 16.

Khadija Marouazi

Translated from the Arabic by Alexander E. Hinson

In the face of how powerful things were as they took the form of the mundane, we continued to live through a period of crisis without the appropriate discourse that could capture what we were going through every day, shed light on the specifics, and point to a personalized awareness and ebullient language. Nothing like that was there, but something of it had started to appear on the horizon. My mother, Rabiha, was the one who abruptly ended this whole crisis. The event is still etched into my memory, but whenever I retell it, it seems fresh and new. My mother, Rabiha’s days consisted of nothing more than standing in a line of women cutting pieces of fish for canning. My mother joined the party when Mehmad insisted that she come and bring some other women, but she never told anyone. The covered truck transported their bodies like stacked pieces of wood, and their exhaustion was obvious. But she knocked on the back window to get the driver’s attention as she pointed to a spot by the side of the road.

“Leave me next to the party placard, please.”

“Are you sure? Everything alright?” The women turned to her peppering her with questions.

“Everything’s fine. I’m just going to do what’s right. Some professor is coming from the capital and Mehmad told me to come. He made sure three times that I was coming.”

The meeting was open to the public, but despite that, the hall was only big enough for party members and some sympathizers. We turned around when we heard the swish of heavy steps mixed with the sardine smell emanating from the timeworn haik and from her entire body. My mother, Rabiha’s body still had a swagger that was garbed in confidence and pride, despite the fatigue that hung from her face. Despite her weariness and despite her advanced age, there was still a glow surrounding this woman. She let her eyes wander around the hall and gave a spontaneous greeting. She walked to the second to last row. She dragged a chair toward her after putting her basket to the side and dropped down onto the chair. A body whose very shadow revealed how tired it was. Hours of toil reproducing itself to draw swollen pockets underneath her eyes and cracks all over her hands. But nothing could hold back the glow from her eyes, from her entire face.

I wasn’t more than a row from her when she turned to me with a question as soon as the speaker entered.

“That’s the professor?”

“Yes, it is.”

“He came from the capital?”

“That’s right.”

“Poor guy. And how long is he going to keep us here?”

“According to the program, three or four hours,” I answered, barely able to suppress my laughter.

“Oh my God, what does Mehmad want with me when I have to get up at five in the morning for work!”

The speaker sat down. To his right sat members of the regional office, one of whom presented him to the audience. He spoke of the importance of the presentation’s subject which was established by preparing to engage in community mobility, and how the presentation would monitor the role of the intelligentsia in the process of engagement. He finished by handing the microphone to “the professor,” as my mother referred to him. He began with a pure theoretical framing around the intelligentsia in Marxist literature and focused on selections of Gramsci before moving on to the role of the intelligentsia in this country and how it gets along with politicians at this stage. The presentation lasted about an hour and a half. Every once in a while, I turned to steal a glance at my mother who kept sighing, passing her hand over her mouth, her head nodding back a bit. The woman slept fitfully. She was exhausted. The presentation ended and I thought she would leave as soon as it was over, but she remained glued to her chair. Maybe she knew that leaving before the others would mean Mehmad would lose out on the point he wanted to make by having her come. Maybe.

The floor was opened for questions and comments, of which there were a few. Mehmad’s voice came to us alerting us to the fact that there was a finger raised in back. I turned and there was my mother, Rabiha, raising her hand, fingers outstretched. Her questions still ring in my ears.

“Thank you to the professor for what he has said. You talked a lot about the intelligentsia, but you didn’t say how this impotence of his would be cured. With a doctor or fqih or what? And another question: This Gramsci, from France . . . Does he have any connection to the fqih, Germachi, who lives next to us? Or is it just the same name?”

The hall shook and the confusion hung in the air. The intelligentsia, as far as my mother was concerned, was nothing more than a sexual problem (confusing the word intelligentsia with impotence), and anything foreign was in France. For her, Italy and England were just French cities. If we searched for his family roots, surely, we would find that Gramsci was closely related to the fqih Germachi, and if so, my mother would insist that Germachi’s prescription was ineffective in solving the problem of impotence, underscoring the fact that impotence was something that happened to men all the time. As for us women, God has spared us of it. She said her piece, then she slipped out of the room.

I only told that story rarely. I carried it with me, rumbling inside for whenever discussion on a specific topic shifted to something theoretically and conceptually vague.

No one in prison can understand that a political detainee has anything to do with them, these exhausted masses. They always look suspiciously at political detainees as if they have some sort of a connection to power. I, for example, am here because I am against authority and want to replace it with my authority. But in the eyes of the regular prisoners, this does not at all mean that these political detainees who are scattered throughout the country’s prisons are there paying the price out of love for those prisoners. To the regular prisoner, the political detainee’s love is only for herself. And only we are able to swallow this talk and easily chew it without realizing that those we are talking about are not represented by it. In fact, they can’t stand it. The distance is vast. A chasm that cannot be filled with just words. That’s how the relationship between the Left and the opposition to these masses seemed to me. I didn’t imagine that I would enter into a constant state of alert to defend my identity here in prison. When I was being held in secret detention, even during the trial, I felt that what I was doing was insignificant when compared to how much torture they were inflicting on me, and how serious the accusations were. So, at first, I said to myself how happy I was that “I was involved in something big.” That’s what I said to myself when I saw the charges wrapping themselves around me. But as soon as I arrived at the Chekarem municipal prison after the sentence was handed down, I was transformed into a series of sparks that spewed in every direction when I tried to pull back any piece there was of my identity. I underlined it in red. Daily life in the women’s ward experienced constant troubles and upheavals that pushed relationships to their worst. The reading lessons I had started with Safia and ten other women who had never deciphered a letter became, according to the smears of the prison warden, a political cell that I was using to incite unrest. I lost my cool and defended it with everything I had, but soon realized I didn’t have anything at all. That’s how prison is. As soon as you’re thrown in, you feel a sharp pair of scissors cutting out a large part of your dignity. In fact, I felt that the prison machine was intent on humiliating us for the rest of our lives. Once I asked myself: Are these the masses for whom we pay so dearly with our lives? Much of the fresh purity I had used to sketch them here inside me had started to dry up and turn brittle.