Beirut, My City is a 1982 documentary by Lebanese filmmaker Jocelyne Saab (1948-2019), filmed during the 1982 Israeli siege on Beirut. It’s considered part of the Beirut Trilogy, which also includes Beirut, Never Again (1976) and Letter from Beirut (1978). The film’s script is written in French by Lebanese actor, playwright, and director Roger Assaf. As I watched Beirut, My City in Oakland a few months ago, I listened to the script and thought, “This is a poem!”

I was haunted by Assaf’s words for weeks and decided I wanted to see them on the page and translate them. They were beautiful and heartbreaking, and I wanted them to exist for English readers. I contacted the Jocelyne Saab Association, and they were generous enough to send me a pdf of the French script. It’s funny that, as I was translating it, it never occurred to me to refer to the English subtitles. As far as I was concerned, I was translating a poem or a lyric essay. I hope this translation resonates with readers as much as the French did with me. Tragically, it feels as if Assaf wrote this today.

Simultaneously, as I translated from California (where I had moved less than three years ago) and watched the news about Lebanon and Palestine, I began writing letters to Roger. You can read the letters here. —Zeina Hashem Beck

There that’s my house what remains of it

and I can no longer bring myself to tell you about the others it’s cynical but

there you go here is my bedroom here we were preparing a film

it was two floors ultimately it’s not grave because

it’s nothing but walls after all and we all came out of it alive

to think of the number of the dead in the past two days

on the one hand because of Israeli bombardments

because of internal fighting I don’t know we wonder I ask myself questions

the essential thing is to survive to live it’s true that this house is tradition

that it does something to my heart that it is 150 years of history

it is my identity it’s the same for everyone

it’s the identity of all the Lebanese who lose their houses their belongings

furthermore when we don’t know our points of reference

we no longer know who we are

Jocelyne Saab, 1982, in Beirut, My City

[city sounds / walking in the dark / explosions]

When did all of this begin? A gloomy Saturday or a dismal April, a few years ago. The war took its time, or rather it took our time. A slice of life, disappeared. So that, for many of us, between childhood and maturity, there is a missing word: the word youth.

Today, the dates are muddled. In the span of a moment, images collide and clash to acquire the form that memory will take when appearances dissipate.

[shooting / warplanes / saxophone / shooting]

There was a madman in the city: Abu Richeh. Beautiful, poisonous flower in a gangrene-struck city. When he was filmed, we didn’t know he was a spy, a disguised Israeli military. We didn’t know what Beirut was hiding, and neither did he nor those who placed him here.

One always believes what one sees, and what one sees is always deceiving. The madman wasn’t a madman, and the city wasn’t what she appeared to be. Beirut, brothel city, whore city, wicked stepmother city. That’s how we perceived her before, that’s how we spoke of her. The finance, the spying, the aggressive and destructive modernity, the most brazen political bribery, the market of trafficking and treason, all of this seemed to be Beirut. What didn’t it take for the image to reverse, for the illusion to crumble, and for the stone to begin speaking its truth.

[singing in Arabic: “Beirut, city of history, without history. Your history, Beirut, is dying men.]

When we were struck, when our families or our close ones were struck, we suddenly realized how intimate the besieged city was with death. Karim, the sweet and tender Karim, Karim the beneficent, killed by the war. Nothing resembles him less than the violence of his death. Today we understand to what extent his name belonged to him —Karim means generous, and all of us who knew him had, at least, even in the worst of moments, a friend.

[music / saxophone]

All that is empty is full, that’s what war is. The bombs create holes, voids, tombs, and life pours in, filling all the vacuums where death wanted to be definitive. Every place becomes a history. Every name becomes a memory.

Suddenly, one day, there was West Beirut. Beirut el-Gharbiyyeh, isolated in its box of fire, of iron and hate. And then there was what we called the other side, East Beirut, so close and yet so far, beyond the locks, behind which expressionless spectators could no longer see in the besieged city anything but a magma of horror and atrocity, where life must have been impossible.

Since the beginnings of the civil war in 1975, Beirut, divided in two, breathed, despite everything, through the passages that the violence of the conflicts hadn’t completely severed yet. Until the day Sharon encircled East Beirut and imposed his verdict. Accused of coexisting with the Palestinians, the population of West Beirut was condemned. In which direction do we close the gates of the city? Who was the prisoner of whom? Who held the other at gunpoint? The one who, in West Beirut, deprived of electricity, of running water, of flour and fresh food, used leaking pipelines and connected his TV to a car battery to watch World Cup matches with his neighbors? Or the one who, in his armored tower, on the other side of the city, invisible to us, whose only language was a deluge of bombs of all calibers and a gigantic, deathly, and powerless machinery, rotted in his rage to defeat a city that defied him – the executioner reveals the beauty of his victims, and the city’s truth gushed forth from all the wounds inflicted on her living body.

[water sounds / music and saxophone / planes / car honks / shooting /

The old gardener, in Arabic: this garden, I’m the one who planted it

Here, it was full of garbage, I alone removed it, no one helped me,

plants are stronger than their bombs

do you see them? there they are what can we do the eye sees

the hand can’t grasp I’m not scared anymore

the planes are above and I’m here let them bomb

we’re in the right, and that’s all that matters]

Too often we’ve described the horror and devastation, too often we’ve narrated the death that fell on us, that came from elsewhere. Ultimately, in wars, the images that we retain, that we like to spread, are those that reflect the enemy’s presence, his war, his crimes, his images projected upon the city. All these images of death accumulated until we stopped seeing the men who clung to life with such passion that they birthed the city and gave her a soul.

[the song “Beirut” plays]

We said, “I’m from West Beirut” with a tinge of pride and the conviction of having exposed the proportions of the Israeli army, of having forced it to display all its strength and thus reveal its powerlessness. And when we were asked, “How are you?” we responded, sardonically, “Baa’dna ‘aychine, still alive!”

[seaside waves / song / planes / shooting]

We said, “I’m from West Beirut.” And for once we had a language and an attitude that surpassed the petty norms of small communities. We could be Shiite or Christian, Jewish or Sunni, Lebanese or Palestinian — truly, faithfully. While being, at the same time and in the same space, someone from West Beirut. Where a possible society was being shaped. One with a certain Arab dream — unfulfilled desires of a condemned people. Beirut, agonizing, had the traits of utopia. Being Lebanese and Arab, it was possible. Jewish and Palestinian, it existed. Muslim and progressive, it was done. Woman and leader, we had that. Anarchist and organized, this was common. But utopia has a high price, and we didn’t know yet the bill would be diabolically increased.

[From the Qur’an: “Say, O Prophet, “I seek refuge in the Lord of humankind, the Master of humankind, the God of humankind, from the evil of the lurking whisperer —

who whispers into the hearts of humankind — from among jinn and humankind.”]

How long the road is between what’s felt and what’s said, between what’s said and what’s perceived. Words labor, run out of breath. The unspeakable is more powerful. When grief becomes spectacle, we’ve already betrayed it. We are already tourists in the country of suffering. The measure of compassion isn’t that of pain. And faced with the rubble of a bombarded building, an undefinable distance separates those who are moved by what they see and those who weep for what they no longer see.

[planes / music / horses galloping / racecourse crowd]

But destiny stored for us the reverse of an image we thought we’d already encountered. All the corners and recesses within the reach of bullets or bombs bore the marks of the multiple wars we’d been through. The space of images has only two dimensions. One must strike much deeper to uproot them. As the Arab expression goes, one must act as if they never existed. They must be undone. The images must be terrorized so that men choose to forget them. And yet, there are images I’ve seen so often, resembling images I’ve seen again and again, that it seems to me it’s them who look at me, it’s them who recognize me.

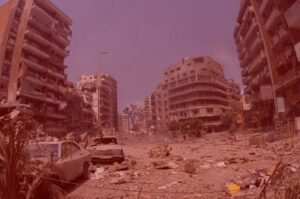

The streets and walls of Beirut’s ravaged neighborhoods, walls that no longer shelter anyone, spread across streets that lead nowhere. Indistinct message for the vagrant here. Neither path nor residence, all is denied them. The proof is the emptiness of their non-existence. And when the bulldozers perfect their work, we’ll be able to say, “Here? There was nothing!”

[jazz music]

The ruins of Fakhani, Sabra, and Chatila offered visitors what appeared to be the ultimate devastation of an ending war. And we couldn’t yet see in them the setting of a massacre on hold. A little more time and the picture would be complete. I dare not say finished, for I might be wrong. Quickly, one must defeat consciences and present them with fresh images to keep them completely oblivious. The mutilated cadavers, the gouged-out eyes, the scalped skulls, the bodies disemboweled with axes, will horrify the world and force more palatable doses of voyeurism. But how would this carnage be different from previous ones? And why is the tax on horror selective? Thus the opinion is formed, in which an aerial bombardment is perhaps criminal but not repulsive. Murder with bombs isn’t a barbarian and inhumane massacre. The nuance is technical and the spectacle is perceived differently.

I understand very well why the thousands of prisoners captured by Israel can’t be seen. The tortures they’re subjected to are known, reported, confirmed. It doesn’t matter that they’re recounted, as long as they’re not viewed. The blindfolds placed on prisoners’ eyes, an all too familiar inhumanity, are but a reflection of our own inability to see. Bound by the visible, public opinion always chooses to repress its gaze. And on the other side, on the side of the victims, the trial doesn’t lie in the shocking instant, but in the duration, in the daily price of a challenge that’s too human, and thus too disproportionate. The price of utopia.

[singing upon the departure of Palestinians]

Now that West Beirut had survived, now that its story had ended, its memory needed to be domesticated. Armed Palestinians had atomized powers and allowed even the most unreasonable to hope, but West Beirut wouldn’t be able to hold on to this nostalgia with impunity. Nothing is more dangerous than a people that has perceived its desires. In the interweaving of the sordid and the sublime which was our story with the Palestinians, what emerged again was nostalgia, the nostalgia of desires that were, at times, experienced. The Fedayin’s farewell, with its epic air, the immense liturgy in honor of their departure, was but an expression of our recognition. It was a re-cognition. The thousands of dead, the months of siege and deprivation, the terrifying panoply of bombardments, phosphorus, implosion, fragmentation — we had suffered, accepted, and paid everything, in our flesh and our stones, to protect an image of ourselves we thought we deserved, and to not see an Israeli tank in the streets of our gutted city. In the end, we had renounced everything but that. But it was wishing for too much. The dead weren’t dead enough, the living too intact and their gazes too full. These men and women in the port of Beirut thought that their story was done, that their role ended here, and that this was a sad ending, but at least now came the time for rest. They were mistaken. How many among them returned to their modest residences in Sabra and Chatila? A lot for sure. It was them who were traveling further.

[gun salutes / singing / ululation]

[jazz music]

Today, I’m in Paris, my eyes open on an immense emptiness. So, from time to time, to have a face, to have a gaze, I close my eyes and I remember.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)