An Arabic proverb states that to understand a people, one must live among them for 40 days. Forty days is the time Jesus is said to have wandered in the wilderness. Remembering a loved one or a friend on the 40th day after death is an Islamic and Eastern Orthodox tradition. Khaled Khalifa died on September 30, 2023. In this essay, a fellow writer considers Khalifa in the context of both Arabic and world literary canons.

Youssef Rakha

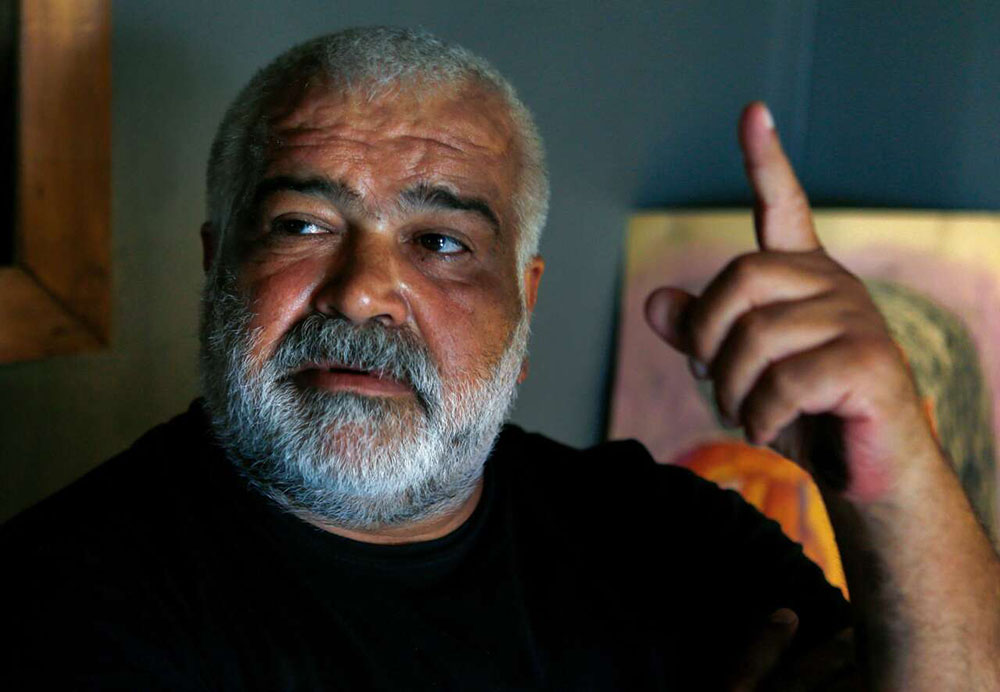

When I heard of Khaled Khalifa’s death it was a shock. I knew he had heart problems. I also knew he ate, drank, and smoked voraciously. But it conveniently escaped my notice that, being twelve years my senior, the affable, gregarious Syrian — who, though not a close friend, always called me Abul Youss — was nearly sixty.

I was especially shocked because I’d been thinking about him. His new novel, No One Prayed Over Their Graves was published in July by both Farrar, Straus and Giroux and Faber, and few Arabic books I know have had as much positive press across the Atlantic over the course of the past few months.

The other day I enthusiastically “liked” the tweet in which Khalifa thanked his translator Leri Price and his agent Yasmina Jraissati, commenting on the book’s nomination for the National Book Awards for Translated Literature. His previous novel, Death Is Hard Work — which received the same level of interest and praise — was a finalist for that prize in 2019. In the meantime, taking their cue from the anglophone sphere, publishers across Europe and beyond have translated his work into over 20 languages.

This is interesting because, back in 2012 when his first long novel, In Praise of Hatred, was published in English, Khalifa was regarded more as a commentator on his country’s crisis than an author of international significance. By decade’s end this no longer seems the case — but Khalifa barely had time to bask in the recognition…

By the the 2012 release of In Praise of Hatred’s English translation, Khallouda (as his friends called him) had evidently become the West’s acknowledged Chronicler of Modern Syria. Many earlier figures seem more deserving of the title — the novelist Hanna Mina (1924-2018), for one — but Khalifa’s work was solid enough for Mina to approve of him bearing it.

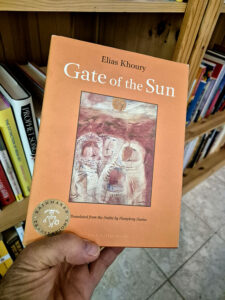

Before that, however, it was In Praise of Hatred that made his name in Arabic. Published in 2006, it is the story of a generation of women from the Aleppo countryside — where Khalifa comes from — told by their niece, who is a medical student at Aleppo University when the clash between the (Alawite) regime and the (Sunni) Muslim Brotherhood that results in the infamous Hama massacre of 1982 breaks out. Witnessing sectarianism shatter her own family — one aunt elopes with a death squad officer, another ends up with her Yemini husband in Kandahar — the Sunni girl cultivates hatred for all the other sects, only to end up encountering and bonding with members of those sects for the first time in prison.

With elements of magical realism — the influence of Gabriel García Márquez is something Khalifa shares with most Arab writers of his generation — In Praise of Hatred is filled with flesh-and-blood women persuasively inhabited by the author’s consciousness. Khalifa told the novelist Khalil Suwaileh that, in the 13 years it took him to complete the book, he sought to “expose the culture of hatred on which all fundamentalist movements that we see today are built.” Reflecting the bigger questions in an unsentimental and always intelligent way, those women’s tragic life stories manage to do just that.

“I want the Syrians to reread history,” Khalifa told Michael Safi in The Guardian in July, “and to ask who expelled the Syrian Christians and Jews from their city — who are the children of our country — and who thwarted their great industrial project and their attempt to be part of the civilized world. The question today is, who decided that democracy is forbidden to this country?”

Khalifa’s work does interrogate history but without betraying its commitment to literary art. In his 2022 craft book, An Eagle on the Next Table: Notebooks of Isolation and Writing, Khalifa speaks of “the writer’s self-delusion” and how writing is thus “a multilayered act that only history can sift through, freeing good writing of bad writing.” It doesn’t matter what the writer themself thinks of their own work, since “the problem is that most writing is bad, and good writing a rarity.” He implies that such delusions of high art are however necessary. “My previous life,” he writes, “is nothing but heavy footsteps on cold tiles. My life before writing is all noise, which I can now only justify by the fact that it had to be lived. Those feet had to take those brash steps to get to silence.”

For Khalifa, just as for the form’s most sophisticated practitioners, each new novel is an exploration of what a novel can be: “To write a novel in the same way, in the way you know and in the language you have already tried out, is like seeing a city for the whole day through the glass of a café, believing that all those details will recur the next day: the angle, the waiters, the passersby, the trees. Writing like this produces a text that can only run a few steps before falling dead. Even if it is one in a million, the possibility of surprise is worth the risk.”

But high art and literary innovation are almost certainly not the reasons Doubleday took on In Praise of Hatred right as the Syrian revolution was turning into a civil war. Without Khalifa’s permission, his publisher excised the last chapter in which the once-fundamentalist narrator, having ended up as a resident doctor in London, takes off her pious attire, finally renouncing the sectarianism of the title. Evidently Khalifa could only be read in the West so long as he didn’t question such hatred being the inexorable fate of Syrian humanity. The novel could have mainstream publication – but only by affirming the belief that the Muslim tendency to embrace violence must be innate, irrevocable.

In Death Is Hard Work, three siblings attempt to convey their father’s corpse from Damascus to the village of Annabiya, the burial place the father specifies before he dies. It is a raucous, beautifully woven and often comic road trip that doubles as a horrific showcase of the heartbreak and the absurdity of the Syrian tragedy. By 2019, when it came out, Khalifa was being praised in far less topical terms, though the New York Times compared him to William Faulkner — a writer whose work is both less fantastically and more poetically inclined — on the basis that both wrote against a backdrop of civil war.

No matter how compelling, contemporary writing in Arabic just isn’t part of the Western gatekeepers’ conception of world literature — especially not if it tries to be innovative.

The reason I find myself identifying with Khalifa is something altogether different, however: a sentiment perhaps best expressed by Libyan American writer Hisham Matar reviewing Death Is Hard Work in The Guardian. “The most amazing thing about this book,” Matar wrote, “is that it managed to exist, that it came to us out of the fire with its pages intact.” The implication that the validity of the work derives from its subject matter and the circumstances of the writer, not from the text’s own achievements — that’s why.

It was equally as a result of the Arab Spring that my second novel, The Crocodiles, was taken up by a relatively mainstream US publisher (a deal facilitated by the same Jraissati), though the response was somewhat more muted when it came out. Still, it was a significant moment — my first, longer and comparatively untranslatable novel The Book of the Sultan’s Seal appeared in English at around the same, too — and I hoped it meant that my original vision for my Arabic writing career might come to pass.

Back when I’d started writing novels in 2011, I had envisioned being part of that global conversation about history and identity already taking place through fiction and translation for decades. But I only ended up feeling cast out of the hypothetical literary canon. Over the years my disillusion has been assuaged by the realization that this has less to do with my aptitude than with who I am: no matter how compelling, contemporary writing in Arabic just isn’t part of the Western gatekeepers’ conception of world literature — especially not if it tries to be innovative.

Today, things have undoubtedly improved somewhat: the tide has turned, at least momentarily, with Jokha Alharthi winning the International Booker, for example. But by and large the Arabic novel is still only allowed to exist as an echo of world news. And what could an experimental provocateur who often sets out to subvert the orthodox narrative of what the news might be about hope to achieve in this context?

Perhaps the secret of Khalifa’s success, I have been thinking, is that even though he is equally innovative, the story he has to tell or the way he tells it is better aligned with the desired narrative. It is interesting, for example, that his characters tend to be representatives of historical currents. Unlike me, he isn’t likely to show how the individual story belies the grand narrative. He is not especially interested in madness or desire. By the time The Crocodiles was published at the end of 2014, what is more, the political situation in Egypt was no longer newsworthy. In Syria, by contrast, the plot in which the West had direct stakes only thickened.

But, even if the Arab Spring was the impetus for its success, by now Khalifa’s work is in a different place. It remains significant and personally validating for his work to be seen as literature that transcends political praxis. The Western publishing machine may have used Khalifa to support a specific agenda at the start, but now that his books have taken their place alongside work from languages stamped with the global seal of approval perhaps he — we — can have the last laugh.

Khalifa was the real thing, and not just in literary terms.

Between 2013 and 2019, whether out of fear of political detention or despondency with the failure of the revolution, many intellectuals and activists chose to leave Egypt. At the same time, Syrians were being displaced en masse, fleeing for their lives as cities including Aleppo were bombed by the regime and its allies, and jihadis were establishing their own preposterous emirates across the country.

Khalifa’s books were banned in Syria. Riot police broke his arm during one friend’s funeral in 2012, and, two days later, another friend, the young filmmaker Basel Shehada, was killed in Homs. I imagine he had been intimidated in all kinds of ways, too. But, like me — though at far greater risk — Khalifa chose to stay. He continued to cook in his apartment on Mount Qasioun, living alone. Since his death the testimonies of his friends suggest that the solitude had been taking its toll on him.

Both within the country and across the world, he traveled frequently to ameliorate the worst of his loneliness — it would have been very easy to stay in the West, and adopting more aggressive anti-regime propaganda would probably have helped his career, too — but he would often cut short his longer stays abroad to return to Damascus. Drawing on lifelong familiarity with the Baathist regime of Hafez Al Assad and his son, I imagine, Khalifa mixed pragmatic cautiousness into the intense abandon of which his much younger friend, the Berlin-based writer Rasha Abbas spoke in a moving elegy:

“You gestured to ask what I would drink. I showed you the water bottle and said I only drink water now to watch my weight. You shook your head with disdain for the idea. You had the power of mockery over me, which I handed over to you since I first knew you, sixteen or seventeen years ago? Anything of the kind went against your mind, any practice that chains the human being’s pleasant mood: a diet as much as any self-censorship or rebuke, or worrying about one’s image before others.”

I’ve also found out that, in the last few years, Khalifa had stopped smoking and taken up painting. He was still unable to stay away from Syria for too long, though, and according to friends who stayed with him that summer in Zurich — the last place he to which he traveled abroad — the horrors of war had taken their toll on his vitality and humor.

“I awaited death many times,” Khalifa told Suwaileh not long before. “I gave in to the thought of it happening, and no longer felt the terror that even talking about it will instantly spark. I stopped being superstitious, too. It may be that this way of developing my relationship with it will make my life easier. But the deep thinking required of writing death does turn it into a daily chore, like eating and drinking. Writing helped me to accept it, and also to make it beautiful.” Many of Khalifa’s friends have intimated that the idea of suicide recurred to him at various points in his life. Still, in this same conversation, he goes on to say: “The idea of suicide went away into an obscure corner.”

Khalifa survived a difficult coming of age: he was one of 13 children born into a traditional family, and didn’t know how to finance himself until he started writing television scripts. He also survived one of the 21st century’s ugliest and most brutal wars. But the life he lived — the glorious Syrianness he had embodied against the odds, never turning it into a slogan or a bargaining chip — caught up with him before he turned sixty.

I have not yet read No One Prayed Over Their Graves, which Khalifa described (in the same Guardian interview) as “a novel about lost love, death, contemplation and nature in our lives, about the making of saints, about epidemics, about disasters, about a people’s attempt and struggle to be part of global culture, about the struggle between liberals and conservatives, about the eternal coexistence of this city, about the city at a time when the whole world was seeking to move to a new stage.”

Spending time with it in the Arabic original will be my way of bidding Khaled Khalifa farewell, and there will be some consolation in knowing that it was published and celebrated not as a new novel about the tragedy of Syria, but as the piece of true world literature that it is.

Wonderful review. I learned so much more about Khaled, his work, his passion and his life both before and after the war. Thank you, Youssef, and to TMR for publishing this moving piece.

Thank you so much, Lawrence. I’m really glad the piece brought Khaled closer