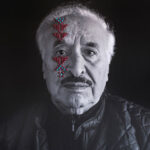

Embroidered Palestinian stories by photographer Rasha Al-Jundi, in her series When The Grapes Were Sour: Embroidered Palestinian Stories from Exile.

Rasha Al Jundi

“We must choose the identity, not let the identity choose us,” says Hamzeh, 27, from Al Mansi–Haifa and Burqa–Nablus. The chosen pattern of traditional embroidery is “Cypress and Balance,” from the Hebron region.

When The Grapes Were Sour: Embroidered Palestinian Stories from Exile is an ongoing multimedia documentary photography project that was launched in October 2022, which combines portraiture, audio and hand-applied traditional Palestinian embroidery. Depending on the stories, related archival material has also been incorporated into the photographs.

The words of an older Palestinian woman, featured in the film The Land Speaks Arabic, inspired the project’s title. She recalled the time Jewish Zionist armed groups, the Haganah, attacked her village during the 1948 Nakba, or catastrophe, and said in Arabic, “When the Grapes were Sour.”

Threads of History and Family Tradition

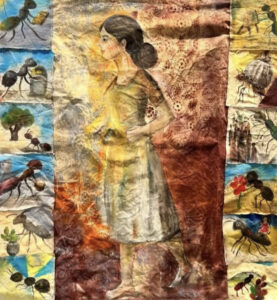

Evidence from the Canaanite statues found in different parts of occupied Palestine illustrates that embroidery started approximately 4,000 years ago. It was used to decorate clothes, and it spread to many parts of the country, except for cities that adopted Turkish fashion without embroidery, and areas from the south of Nablus to south of Nazareth, where women worked in agriculture.

Embroidery took simple geometric forms before British colonialism, and new forms adapted from foreign magazines such as flowers were introduced during the Mandate period. Palestinian women also designed the embroidery motifs themselves. They relied on inspirations, predominantly from surrounding nature and daily life for their designs. Cypress, grapes, water, feathers, stars, roses, the balance, birds, the baker’s wife and four eggs in a pan are but a few examples of common motifs. Others carry names referring to their usual positioning of traditional dresses (either on the collar, bottom sides for instance).

In general, traditional Palestinian embroidery reflected traditional rural life, the Palestinian people’s connection to the land, its history and what it offered them. After the Nakba, many exiles sought to keep Palestinian embroidery alive, either through the continued practice of embroidering dresses or by incorporating it in new alternative ways.

Since 1948, there have been several attempts by the Israeli occupation to appropriate it. However, in 2021, UNESCO added the art of traditional Palestinian embroidery to its Intangible Cultural Heritage List.

In my own family we’ve always embroidered, and I embroidered the cross-stitched patterns that appear in the photographs. In addition to referring to privately owned embroidered family dresses, I also relied on The Guide to the Art of Palestinian Embroidery Art, by Suleiman Mansour and Nabil Anani (2011), and Palestinian Embroidery Motifs — A Treasury of Stitches 1850–1950, by Margarita Skinner and Wadad Kawar (2014).

Facing Expulsion Today

It has been 75 years since the Palestinian people suffered the traumatic events that led to the Nakba, which started in April 1948. Although the Nakba reached a violent crescendo on May 15, and led to the forced expulsion of more than 800,000 Palestinians, it continued throughout that year. Many have declared it an ongoing assault until today with the continued uprooting and blockading of this indigenous population.

According to figures from the Palestine Land Society in 2022, there are more than 14 million Palestinians inside the occupied territories and around the world, of whom more than nine million are registered refugees. This makes Palestinians the largest refugee population in the world.

Many Palestinian exiles, whether in cities, the countryside or refugee camps, still hope to return to their homeland. With time, this dream and the internationally acknowledged right of return get more complicated. Yet, it never completely disappears from the minds and hearts of some exiles. Others chose to erase their connection to their roots either due to trauma, shame or hopes of shaping a firm identity by adopting a new one.

Since October 7 of this year there has been blind support for Israel and in some political quarters calls for the complete annihilation of Palestinians in Gaza and beyond. At the time of writing, coordinated collective efforts by European governments, including Germany, France, the UK and Austria, have aggressively silenced and banned any form of Palestinian or pro-Palestinian group demonstrations, candlelight vigils and sit-ins.

Palestinians are witnessing the forcible removable from their land, which is unfolding on occupied homeland at the same time they are being subjected to authoritarian silencing abroad.

Through When the Grapes were Sour, I create personal accounts of individuals who identify as Palestinian exiles from around the world. I see myself in each of these stories through the embroidery. It is my intention to keep this vital part of our cultural heritage alive, while we struggle with our identity, fragmentation and the presently hostile political climate against Palestinians’ right to self-determination.

*@embroidered_exile is a dedicated Instagram page for When the Grapes Were Sour: Embroidered Palestinian Stories from Exile.

**The exhibition, Material Power: Palestinian Embroidery, explores the historical and contemporary forms of Palestinian embroidery, curated by the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Rachel Dedman. The exhibition, at the Kettle’s Yard, in Cambridge, England, until the end of October, will move to the University of Manchester in November.