In Alireza Iranmehr’s short story, two lonely people pass time together under the state of emergency that has become Iran.

Alireza IranMehr

Translated from Persian by Salar Abdoh

That autumn night, I lay quite still next to her. Her name I have forgotten. How is that possible? Though I remember the half-moon tattoo on her left breast and the fact that our connection had something to do with the emergency that is the permanent state of things here. Sometimes she’d call in the wee hours of the morning and tell me she needed a warm body beside her. Sometimes it was me who called and said the same thing. We didn’t say much beyond this to each other, ever.

But that night she was talkative. “It doesn’t matter who is here. It’s the loneliness. I want to reach out to you on those occasions, but I don’t. Not as often as I’d like. It’s been three years with us, you know.”

What she said was obvious, and sad. I was surprised, though. It was as if the violence on the streets, the demonstrations, made it so that what existed between us should only happen in silence — an unspoken contract that dictated that only our vulnerable bodies should speak, not our lips.

I asked, “Then why not try to live with someone?”

“Because that someone would have to love me first, or at least like me, before I decided to spend a life with them.”

She was attractive. Obviously had money or a good job. Her apartment was spacious. And she seemed to know more than enough about life that she hardly needed to speak of such self-evident things. It dawned on me that we had not needed to like each other at first to come together. There was no jealousy between us. Now and then she’d mention, in a mere sentence or two, other men who were occupying her life.

“You mean in these three years that we’ve been seeing each other there was no one else who … liked you?”

“There was. There is. Trouble is, I have to like them too, no?”

“Why can’t you like them?”

“I can. And I do. But then a man goes and says something that I’ve heard before. The same sentence. The very same words. In that moment everything ends. You know why? Because the things people are able to say to each other are limited. When it turns out there are more people in your life than words to contain them, it gets hard to want to continue.”

I had closed my eyes. Now I opened them and saw that her face was shining in the moonlight coming through the window. Across the street, the remnants of yesterday’s broken windows and tear gas were about to become memory.

I said, “It’s true. Words start to dwindle. That’s why we get lonely. Not just solitary, but lonely.”

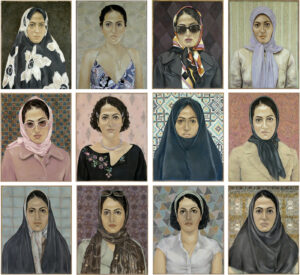

She pressed her fingers into the white hairs of my chest. “When I was nineteen all I wanted was a regular guy, one who went to work in the morning and came back in the afternoon. A husband. At twenty-five I wanted a man who didn’t repeat himself. Someone whose presence didn’t dumb me down. A partner who didn’t crush my own aspirations with their smallness. At twenty-seven I wanted faithfulness, a man whose body didn’t reek of other women. When I turned twenty-nine my preoccupation was love. Thirty made me long for someone who wasn’t jealous, someone who didn’t imagine things, someone confident in our bond. Then, at thirty-two …”

“At thirty-two?”

“I just wanted to be alone.”

I continued to gaze at her in wonder. “Now what do you desire?”

“Now I’m scared of being alone sometimes. Sometimes I want an embrace in the dark. What I don’t want is to wake up in the morning and see a stranger lying next to me, his face brushing against mine. I want him to arrive when it’s pitch-dark and leave before it gets light.”

We made love after that. To this day I cannot even recall if it ended between us on a sour note or not. I doubt that it did. One day I braved the tear gas and the burning streets and came to her house, and she was no longer there — even though I’d long turned into that man who arrives in the dark and leaves before sunlight.