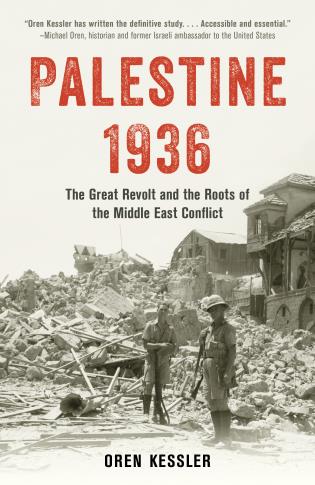

Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict, by Oren Kessler

Rowman Littlefield 2023

ISBN 9781538148808

Brett Kline

This may very well be the first in-depth account for a general, non-academic public of this key, destiny-shaping and extremely violent 1936-39 period in British Mandate Palestine. But it may be a tough read for many people, including for those who fashion themselves minor experts on what is often described as the “Arab-Israeli conflict” — one that has arguably provoked more misinformed or uninformed opinions and racist fervor than any other subject.

Why a tough read? Because the Great Arab Revolt launched in 1936 was the first major explosion of two nationalisms, explained pointedly by American Israeli journalist and historian Oren Kessler in Palestine 1936. The Palestinian Arab sector began a strike that lasted months to revolt against the British colonial power and the increasingly organized Zionist movement by Jews in Mandate Palestine.

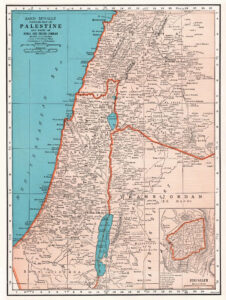

But, as Kessler notes, the violence by Arab gangs and Islamic militias against their Palestinian Jewish neighbors and against British soldiers in Jaffa, Haifa, Jerusalem, Tiberius and throughout Mandate Palestine, and then certain vicious responses by Jewish groups considered to be terrorist organizations, and finally the brutal crushing of the Revolt by British soldiers and police can only be explained within the administrative and political context of the early 20th century Middle East.

And that historical context of the never-ending Israeli Palestinian conflict is still as controversial and emotion-provoking as that last sentence is long. The critical thinking desperately needed to attempt to resolve the conflict for the hundredth time has often been replaced by radical religious and emotion-based violence on both sides. And events today, including the most recent unprecedented attack on Israel by Hamas in Gaza, can be seen within the long line of events since the 19th century.

Kessler does a very good job of explaining the context and the Revolt itself. His first book is a must read for serious students of the Arab-Israeli conflict, as well as for the general public:

The Great Revolt was the crucible in which Palestinian identity coalesced. It united rival families, urban and rural, rich and poor, in a single struggle against a common foe: the Jewish national enterprise — Zionism — and its midwife, the British empire…Yet the Revolt would ultimately turn on itself. A convulsion of infighting and score-settling shredded the Arab social fabric, sidelined pragmatists for extremists, and propelled the first wave of refugees out of the country. British forces did the rest, seizing arms, occupying cities, and waging a counterinsurgency that left thousands dead and tens of thousands wounded. Arab Palestine’s fighting capacity was debilitated, the economy gutted, its political leaders banished.

Kessler explains the context and sequence of events through the lives and activity of leaders on all three sides: Arab, Jewish and British. The most extreme of those figures was the undisputed political and spiritual leader of the Palestinian Arabs, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amin Al-Husseini. After the violence in Jaffa in 1920, he and Jewish extremist Ze’ev Jabotinski were arrested by British High Commissioner Herbert Samuel. Hajj Amin fled to Transjordan, while Jabotinsky was put in the medieval Acre prison.

In 1921, Jaffa was the scene of the first “mass casualty” riots ever in Mandate Palestine, resulting in some 50 dead on each side. Samuel pardoned both leaders, and named Hajj Amin to replace his recently deceased brother as Grand Mufti, “a lifetime position that made him the de facto leader of Palestine’s Muslims. It was, after the Balfour Declaration, Britain’s most fateful decision on Palestine, with consequences more profound than anyone at the time conceived.”

Samuel then named Hajj Amin to head the new Supreme Muslim Council, managing everything once handled by the Ottoman Islamic authorities. In 1936, the Mufti founded and headed the Arab Higher Committee.

The launching of the strike was his finest moment, Kessler writes, but Hajj Amin subsequently refused any negotiations with Zionists or British officials, as they issued numerous declarations and reports, assembled committees and commissions, and often carried out cruel military crackdowns. From his base in the Haram al Sharif in Jerusalem (Islam’s third holiest site with the Al Aqsa mosque, where the British dared not enter), the autocratic Hajj Amin chose instead the path of violence, including against other leading Palestinian families who formed the Opposition.

Some context is needed here. The southern Syrian province of Palestine and all the Middle East were part of the huge Ottoman Empire until 1917-18 and the end of World War I. As British troops closed in on Jerusalem in November 1917, Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour wrote a letter to Baron Walter Rothschild. It began with: “His Majesty’s Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” This was the Balfour Declaration, contested by leading Arab figures.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the land in Palestine was owned by a number of wealthy families or clans (hamulas), known as effendis by the Ottomans, the ayan by Arabs and notables by the British. The names of ayan families, mostly based in Jerusalem, Jaffa and Nablus are well-known to students of the Middle East: Husseini, Nashashibi, Nusseibeh, Alami, Khalidi, Dajani, Tamimi, Masri, Nabulsi and more. Some major landowners lived in Beirut and Damascus.

As they railed against the practice, many were selling land to Palestinian Jewish institutions, settling increasing numbers of immigrants from central and eastern Europe, and Russia. In the 1920s, land purchases doubled to 1.2 million dunams, the Turkish measurement, one dunam equaling one-tenth of a hectare or a quarter of an acre. “At least a quarter of the Palestine Arab Congress Executive sold land to Jews, including its president and former Jerusalem mayor, Musa Karim Husseini, and the mayors of Jaffa and Gaza,” Kessler writes. He notes that of the eight members of the Arab Higher Committee, the AHC, at least four sold land.

At the same time, Jewish immigration from Europe was exploding. There were about 57,000 Jews in Palestine in 1917, including many in Jerusalem, which by the 1880s already had a majority Jewish population. By 1936-7, the figure was at least 400,000, about 27% of the total population. More than 60,000 came in 1935, mostly fleeing Hitler’s Nazi Germany.

When the strike shut down the Jaffa Port, through which precious Jaffa oranges were exported to Europe, Ben Gurion, the head of the Jewish Agency, the Mapai Party and the Histadrut Union, asked the British for permission to build another port in north Tel Aviv. They agreed, providing that the quasi-governmental Jewish Agency find the funding, which it did. Imports and exports shifted from Jaffa to north Tel Aviv for the six months of the strike. That was a great victory.

The Peel Commission arrived in Jerusalem to find a solution to the mounting violence and the increasing rural poverty among Arab fellahin, poor farmers who did not own their land. Hajj Amin ordered the Arabs to boycott. Kessler notes: “The commission had summoned more than 80 witnesses — almost exactly split between Britons and Jews — but not a single Arab. The Saudi, Iraqi and Transjordanian kings pressed the mufti to change course; so did his Nashashibi rivals in Palestine.” The Nashashibi clan of notables led the opposition to the mufti, to the point of being organized into “peace bands,” armed by the British, to fight the Mufti-backed Islamist insurgents.

Finally, Hajj Amin agreed to testify. He reiterated his core demands: ending the Mandate, abandoning the idea of a national home for the Jews (the Balfour Declaration), ceasing immigration and banning land sales. He added that the Wall of Buraq, the Western Wall, (the holiest site for religious Jews, what remains of the second Temple from biblical Jerusalem) was “a purely Muslim place, to which Jews nor any foreign power has ‘any connection or right or claim.’”

Other Arab speakers included George Antonius, author of The Arab Awakening, an Arab moderate educated in Cambridge, and Musa Alami, also Cambridge educated, son of a former Jerusalem mayor, and at one point an official in the British administration.

For the first time, partition was mentioned by the British, but the only real recommendation made by the commission was to cut Jewish immigration to 12,000 people a year for the next five years.

“That dramatic change — cutting Jewish immigration to one-fifth its 1935 figure — was the Great Arab Revolt’s first major, incontestable achievement,” Kessler writes.

It would have tragic consequences for Jews in Europe, first in Nazi Germany, from where a majority of immigrants had come in the three previous years. Suddenly they had nowhere to go, as many countries had already closed their doors to all immigration.

The violence in Palestine continued. Mufti-backed insurgents were repeatedly attacking the pipeline that the British had laid from the oil fields in Mosul, Iraq to Haifa. This was a threat to Britain’s operations in the entire eastern Mediterranean. The answer was the training and arming of Jewish men and women, known as the Night Squads, by an eccentric, very religious Protestant, pro-Zionist British army officer, Orde Wingate. The attacks on the pipeline were reduced by half. And the training and arming of Palestinian Jews by the foremost military power in the world was a victory for Zionists.

There is more, a lot more. Radical, Revisionist Irgun fighters, labeled terrorists, placed bombs in the Arab vegetable market in Haifa at least three times, killing some 100 civilians, including women and children.

After Mufti-backed gunmen killed a high-level British official, Lewis Andrews, in front of a church in Nazareth, the British deported Arab Higher Committee members to the Seychelles Islands, including moderates. Hajj Amin had been smuggled out of Jerusalem, and was living in Beirut, from where he ran the Revolt unchallenged.

It must be noted, as Kessler does, that by the 1940s, the Mufti made his way to Berlin, where he became an ally of Adolph Hitler, helping to form Nazi Muslim brigades in Yugoslavia and directing Arab-language propaganda on Nazi radio. He would never set foot in Palestine again.

Moderates Musa Alami and George Antonius had also left Palestine, the first for Beirut, the second for Cairo.

House demolitions by British forces became common place. Several entire villages were leveled, accused of hosting insurgents. Two hundred houses in Old Jaffa were blown up. Altogether more than 2,000 homes were destroyed, its Arab owners accused of helping the insurgents.

And then on the eve of world war in Europe came the White Paper on Palestine in 1939, issued by Colonial Secretary Malcolm MacDonald. The Balfour Declaration calling for a national Jewish home was dead. No more partition. And Jewish immigration would be officially limited to 75,000 over the next five years, and then would be subject to an Arab veto.

“The Jewish Agency called it a rank betrayal, a surrender to Arab terrorism and a cruel blow delivered in their hour of greatest need,” writes Kessler. In Palestine, Arabs overwhelmingly supported the White Paper. Hajj Amin held a meeting of AHC members in his home outside Beirut to debate its merits.

Kessler quotes one of the members: “…the discussion became more strained as some of us began to realize that Hajj Amin was not in favor of accepting the White Paper…The remaining fourteen members were not only strongly in its favor, but were determined to put an end to the negative policy the Arab leadership had been adopting heretofore…the sole concern of the Committee was now concentrated on convincing Hajj Amin that his negative stand was extremely detrimental to the Arab cause and was serving unintentionally, the Zionist cause.”

Several days later, the Mufti formally rejected the White Paper even though almost all Palestinian Arabs were in favor of it. Why? According to Kessler, his rejection was due to “the continued British refusal to allow him a triumphant homecoming to Palestine.”

And years later, Malcolm MacDonald explained the reasons behind it in the context of the upcoming world war, even as the massive British counterinsurgency was bringing an end to the Revolt. “The Jews would be on our side in any case in the struggle against Hitler,” he said. “Would the independent Arab nations adopt the same attitude? If the Arab states opposed Britain, we would probably lose the war and the Jews would lose the National Home.”

But by mid 1939, the Revolt was dead. Rebel leaders had been killed by the British or by Opposition bands. The figures Kessler advances are generally accepted by historians on all sides. In the three-year period, some 500 Jews were killed in dozens of attacks, most often by rebel insurgents backed by Hajj Amin. Some 250 British soldiers and police were killed by the same fighters. From 5,000 to 8,000 Palestinian Arabs were killed mostly by British forces. Some died at the hands of Jewish extremist groups such as the Irgun.

However, of that number, at least 1,500 Arabs, including deputy mayors and leading Opposition family members, were killed by Hajj Amin’s gangs for allegedly working with Jewish and British officials, which many did. This created an atmosphere of fear in which educated members of the elite ayan families and poor farmers alike dared not express any opposition to the mufti.

In addition, more than 40,000 Muslim and Christian Arabs, especially the political, commercial and landed elite, fled the violence and anarchy of the three Great Revolt years for neighboring countries. Some ended up as far away as South America.

“The economy was crippled,” Kessler writes. “Crops had dried up as landowners fled and peasants were required to provision, feed, and fund thousands of armed men. Thousands of Arabs lost government jobs due to reduced public revenues and doubts over their allegiance…Forcing the British retreat from the Balfour Declaration was the Arab uprising’s singular, undeniable achievement. But the political, social, military and economic fabric of Arab Palestine was savagely, irreparably torn.”

He quotes Palestinian American historian Rashid Khalidi: “The Nakba — the ‘catastrophe’ of their military drubbing, dispossession, and dispersal — was all but a foregone conclusion…The terrible events that bookended the year 1948 were no more than a postlude, a tragic epilogue to the shattering defeat of 1936-39.”

The past is never far off in Israel and Palestine. Hajj Amin named a charismatic, radical Salafist preacher to be the imam of a new mosque in the rapidly expanding city of Haifa. The British had opened the first modern port there, the first international airport and the terminus for the oil pipeline to Iraq. Jews and Arabs flocked to work there.

The new Arab urban proletariat was welcomed by the imam. His name: Sheik Izz Al-Din Al-Qassam. He organized a jihadi group called the Black Hand, and carried out numerous deadly attacks against British and Jewish targets. A wanted man, he and his band were killed by British police in a forest near Jenin. Overnight he became a martyr and a cult hero.

Formed some years ago, the armed wing of the Hamas, today responsible for the incursion by some 1000 men from Gaza into Israel, is called the Ezzedine Al Qassam Brigades.

Amazing read, thoroughly enjoyed your style, details, historical references, etc. Hope you are right in doing such a complex issue the justice it deserves.

What a clear analysis and description of the book. I never understood this part of the modern conflict until reading this review.

Really enjoyed and learned from this perfect length summary of the book. Thank you Brett Kline