Select Other Languages French.

Three Sudanese painters turn displacement into art. In Doha, their work asks: how do you paint a homeland that's burning?

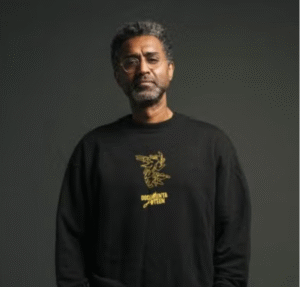

“It’s been such a dark time for Sudan,” said Khalid Albaih. “Having any kind of good news, where Sudan is highlighted — especially through art — means a lot. People feel forgotten. Art is a reminder that we’re still here.”

Sudan Retold, the exhibition and book Albaih co-curated with researcher Larissa-Diana Fuhrmann, opened at Doha’s Alhosh Gallery as part of Georgetown University in Qatar’s Seeing Sudan conference, where scholars and artists examined who gets to define a nation’s culture during wartime.

The project grew out of Albaih’s own search for belonging. In 2019, he and his collaborators published a book collecting work by thirty-one Sudanese artists. “There was so much oral history about Sudan that we were never taught,” he said. “If you’re not an academic, it’s hard to find — especially for diaspora kids. I wanted to know more, and I wanted the next generation to know more.”

The new edition of the book, produced by the Almas Art Foundation with Georgetown’s Center for International and Regional Studies, moves that project into gallery space. Three large paintings by Hazim Alhussain, Waleed Mohammed, and Yasmeen Abdullah anchor the room, surrounded by prints, photographs, and textiles. Yet the opening was defined by who wasn’t there.

“Who is missing right now are the artists,” co-curator Larissa-Diana Fuhrmann said. “Barely any of them are here. While their art can travel, the artists can’t. They are trapped.” Most contributors remain in Sudan or neighboring countries as refugees or asylum seekers under strict visa limits. Their works reached Doha through earlier shipments or digital reproductions.

Sudanese professionals have been part of the Gulf’s social fabric since the oil boom of the 1970s, when teachers, engineers, and doctors settled in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the UAE, and Qatar. That migration accelerated sharply after Sudan’s civil war began in April 2023, as families fled violence to join relatives already working in the region. Qatar now hosts an estimated 60,000 Sudanese, one of the Gulf’s largest Sudanese expat communities.

On opening night, many Sudanese filled the gallery in numbers that surprised organizers. The majority were attending their first exhibition. What they encountered was an attempt to recover what war is destroying: the historical record itself, the version of Sudan that Sudanese people recognize rather than the one written for them.

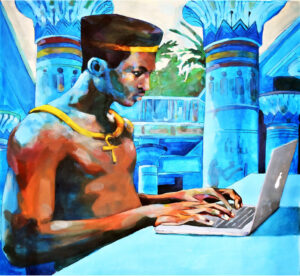

Hazim Alhussain: Painting Parallel Times

Hazim Alhussain works where deep history meets daily life. A cofounder of Khartoum’s artist-run Khaish Studio, he has lived in Doha for over a decade, long enough to become a known figure on the city’s art scene. Curator Abdelrahiem (Rahiem) Shaddad calls him “a phenomenal painter” whose project centers on “parallel times, or parallel existences within one moment.”

“His idea is that our history exists in our current moment. But how does it exist?” Shaddad questioned. “If you took Khartoum before the war, on Africa Street, the fanciest boulevard, you would see a luxury car driving next to a donkey cart on the same road. That coexistence of contradictions is Sudan. And I think this is what Hazim always tries to show: that everything exists at the same time.”

Fuhrmann has followed his trajectory since their collaborations began in Khartoum. “We met in 2013 or 2014 and started painting murals across the city. We ran workshops to help painters move from paper and canvas onto walls.” What draws her to his work is how deliberately he brings long memory into paint, reaching back to the kingdoms of Kush and Meroe that most people know nothing about.

His Doha canvases make that argument visible. Pharaohs share space with bicycles. Ancient hands touch laptop screens. For Shaddad, the painting of a pharaoh at a laptop carries urgent meaning. “We have to confront ultra-contemporary issues: algorithms, big data, the way social media creates a global culture. When I look at that painting, I see his way of saying: hold your culture close, even when you’re living in that global village.”

Albaih stressed the politics embedded in the image. “It’s history and facts. There are 200 pyramids in Sudan, many more undiscovered and unstudied compared to Egyptology.”

The erasure, he argued, wasn’t accidental. “Egyptology once included Nubian studies. Then the Mahdi revolution stopped crossings into Sudan, ending Nubian research.” After that came outright theft. “An Italian explorer blew up the tops of 200 pyramids because Sudan’s pyramids had gold caps. He sold them in Europe. Europeans didn’t believe this was African.”

Hazim’s painted combinations challenge that disbelief with a thought experiment. What if the line hadn’t been cut? What if the old civilization had continued without interruption? The colors reinforce the connection. Fuhrmann noted that the walls of the Doha installation happened to match Hazim’s palette. “We painted the walls, the yellow matches the book’s yellow, the blue matches the blue,” she said. Albaih pointed out the deeper resonance: “Sudan’s first flag was yellow and blue.”

Waleed Mohammed: Painting Fracture

Where Hazim paints continuity, Waleed Mohammed paints fracture. Born in 2000, he is one of Sudan’s youngest artists to gain international recognition, graduating with distinction from Sudan University of Science and Technology in 2023.

Shaddad has worked with him the longest of any curator. “He was one of the first artists in Sudan I ever signed a contract with, back in early 2021.” Known for recreating archival photographs from Sudanese studios of the ‘60s and ‘80s, Waleed explores what he calls “the illusion of being related to memories we were never part of.”

“Waleed’s project is about personal history,” Shaddad explained. “He looks into his own family archives, photographs, personal memory. And through that, he creates relevance for many people who’ve gone through similar things.”

Before the war, Waleed had what Shaddad described as “a gorgeous studio in Khartoum, which was also a hub where other artists gathered. He lost that on day one of the war. He’s never been able to go back.” His current series, Echoes of the Studio, memorializes that lost space.

“The paintings are based on old studio portraits, people sitting for photographs. But he transforms them with contemporary colors: greens, yellows, reds. And the faces are deliberately distorted, stitched, damaged,” Shaddad said. “It’s about the way memory itself gets damaged, the way photographs break down over time. He’s showing that damage directly on the canvas.”

That artistic choice documents broader loss. Albaih connected this to what people now see on their phones. “All of us lost family photos, albums, wedding videos. Look at footage of destroyed houses and you’ll see photos scattered on the ground. Sand has erased faces and details.”

The parallel is exact.

“What you see in those videos is the same in his paintings.”

Waleed now works from his bedroom in Nairobi, where Shaddad also relocated after the war destroyed his Downtown Gallery. The portraits refuse clear faces. They occupy the space where private grief becomes collective documentation.

Yasmeen Abdullah: Inventing a Visual Language

Yasmeen Abdullah meets that grief with invented language. A graduate of Sudan University of Science and Technology, for the past five years all her artwork has been inspired by Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry. Now living in Amman after fleeing Sudan while eight months pregnant, she embodies the displacement that runs through the exhibition.

“Yasmeen is a phenomenal artist,” said Shaddad. “She started a trend that no one else was doing before her.” That trend was creating what he calls personal iconography. “For us as curators, researchers, cultural critics, we always look for iconography. Recurring symbols that represent something shared in a culture. What Yasmeen did was to create her own iconography.”

Her approach draws from poetry but translates into visual codes. “She painted women with long hair and she decided what it meant. She controlled the meaning of her own symbols.”

During the 2019 Sudanese Revolution, she employed colors symbolically, white for revolution supporters, black for dissenters, red for bloodshed. She became part of the “Blue for Sudan” campaign that spread globally after Sudanese security forces under the Transitional Military Council killed more than 100 protesters in Khartoum in June 2019, when the color blue became a symbol of collective mourning and courage.

“Now, after six or seven years, she doesn’t even have to explain it anymore,” Shaddad noted. “People who follow her work have memorized her visual language. If they see a checkered floor, a woman with long hair, a man holding an apple, they already know what it means in Yasmeen’s work.”

For Shaddad, this represents something crucial about artistic independence. “That’s so beautiful, because it shows you can create your own meaning. You don’t have to follow what Picasso did with the apple, or what other artists did. You can create your own language, your own codes.”

A Thousand Faces, One Place

The sense of rescue ran through opening night. Shaddad liked where gallery conversations began, on the right wall, with Abu Shakim’s grid of a thousand Sudanese faces. It set terms for everything that followed.

“I really love the fact that the exhibition starts with the photography of Abu Shakim,” he said. “It’s literally a thousand faces from Sudan. And that project is about individuality, but also about the idea that we all do belong to one place.”

For Shaddad, who has spent seven years “trying to find my own version of Sudan, a version I can connect to, which I can belong to, which I can love,” the photo grid poses a fundamental question about governance and identity. “For a long time, maybe even the cause of all Sudan’s problems, governance in Sudan has been about trying to put us all in one box. But we’re not the same. We keep saying Sudan is so diverse. But then why are we forcing everyone to be the same?”

Moving from the photographs into the paintings reveals the answer. “Different colors, different mediums, different stories, different topics,” Shaddad noted. “And that’s because Sudan itself is so big, and its people are so beautiful.”

The war has forced deeper questions about Sudanese identity that the exhibition grapples with. “Sudan is both African and Arab. We are not just dual, we are multi-ethnic, multi-identity,” Shaddad explained. He has noticed that Sudanese artists who ended up in East Africa after the war “start the conversation from ‘Sudan’s African identity.’ And that tells you something.”

For him, Sudan Retold represents more than cultural preservation. “It’s an exhibition about imagination. It’s about different artists and different creatives reimagining what Sudan is. That’s why it’s called Retold. Stepping away from the written history and going into the oral history, into what we think Sudan is.”

The first time this material left the page was in Berlin. Pandemic, coup, and war reshaped the project, producing what Fuhrmann calls “edition one and a half,” a blending of the sold-out first volume with fresh work. The exhibition moved forward because original pieces survived for a simple reason. “The only reason some survived is because the pandemic hit and I had brought works to my house in Germany,” Fuhrmann said. When she sent photos for Doha preparation, “one artist told me, I thought these paintings burned in my house in Omdurman.”

Albaih laid out the logic plainly. “We published the book in 2019. We had to censor some works because the book needed to reach people in Sudan.” The book travels where people cannot. The room does what books cannot. It gathers a city. It lets strangers feel, as one message put it, “like coming home for a moment.”

Fuhrmann called it “a living moment.” Shaddad called it recognition. Al-Ganim, founder of Alhosh Gallery, called it community. For him, the show continued a long thread of work with Sudanese artists. “It’s about keeping these voices alive.”

After Doha, Sudan Retold moved to the Almas Art Foundation in London, where it runs through December 14, 2025 (Mon-Sat, 11 am-6pm).