Select Other Languages French.

Since the '60s, Nevhiz has created works that range from depictions of systemic violence against Turkey’s left to intimate explorations of existential turmoil.

After Nevhiz greets me warmly at her front door, I follow her down a narrow corridor where large canvases lean against the walls. Her modest flat doubles as both a home and a studio, barely able to contain the artwork she has produced over nearly seven decades. She once had a separate studio on the same street but was forced to vacate it when the building was demolished. Since then, limited funds and reduced mobility — which she attributes to her bad knees — have kept her from renting a new space.

We enter a crowded living room. Moving slowly, the artist carefully lowers herself onto the sofa beside a cluster of remote controls. Next to them sit a few neatly folded blankets and some Tupperware containing her daily essentials, consisting of medication and other small necessities within arm’s reach. I settle into the armchair beside her and notice numerous small works on paper in a portfolio tucked between the two pieces of furniture.

Prior to our interview, she had mentioned over the phone her intention to leave Istanbul for good. Now that we’ve finally met, she explains why.

“For four years I have been under house arrest,” she says. Her tone carries the ironic humor she frequently adopts — mostly to poke fun at herself. “Istanbul has become impossible for me. I move with great difficulty. There are no cabs. Let alone socializing, I’m unable to get to the doctor or dentist.”

Nevhiz cannot wait to move to Fethiye to be near her son and his family, who live in the rural outskirts of the Mediterranean coastal city, one of Turkey’s most popular tourist destinations.

At eighty-four, Nevhiz is an important figure in Turkish painting. She belongs to a generation of figurative painters — including Burhan Uygur, Mehmet Güleryüz, and Komet — who emerged in the 1960s and became known for their distinctively individual styles. Yet her name surfaces far less often than her male counterparts.

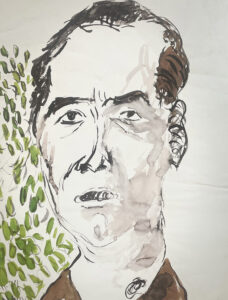

Throughout the interview, a portrait hanging on the wall behind her draws me in with its solemn intensity. It depicts the blind poet Âşık Veysel, a mystical twentieth-century figure in Anatolian poetry and folk music.

When I mention the portrait, along with the writers and poets she has painted over the years, she smiles and says, “I paint people I love, which makes it easier.”

Nevhiz’s diverse œuvre, which spans the personal and the political, sometimes blending the two, has, over the decades, included portraits of literary figures and fellow artists. Among them are two of Turkey’s most influential women authors, Leyla Erbil and Sevim Burak, both of whom she befriended. She has also painted writers she never met, but whose work had a profound effect on her, including Vladimir Mayakovsky, Federico García Lorca, and Turkey’s own Nâzım Hikmet.

Hikmet’s emotionally charged poetry — blending personal reflections with socialist ideals — played a key role in shaping her worldview and, ultimately, her art during her early years at what was then the Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul (now Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University).

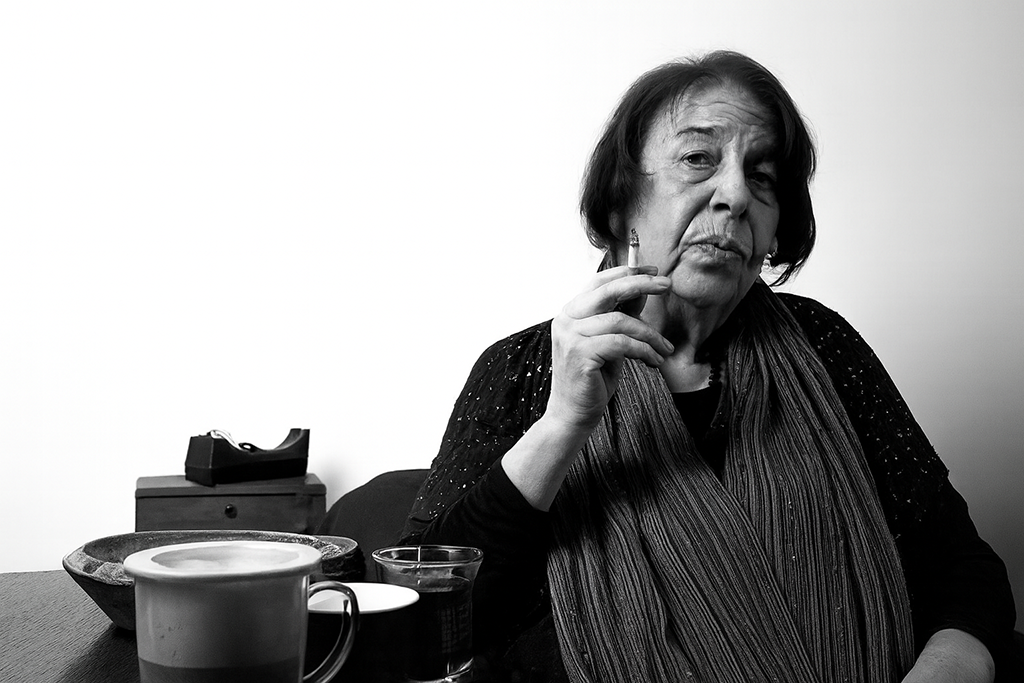

I begin by asking how she became an artist. Nevhiz jokingly warns me, “I might blabber too much,” before lighting a cigarette — only moments after extinguishing the previous one.

Later, she humorously reflects on a recent visit to the cardiologist. “He asked me how many I smoke. I said, I won’t say — I don’t want to jinx it! He gave up on me,” she says, giggling mischievously. Then she adds, “Let’s throw caution to the wind!”

Nevhiz tells me that it was her secondary school art teacher, the first to recognize her talent, who encouraged her to apply to the Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul, which at the time taught students from high school through university. Until then, she hadn’t even known such a place existed.

“When I was fourteen, I wrote in my diary that I was going to study painting at the academy, then go to Paris,” she says.

Nevhiz’s parents initially encouraged her to paint. They bought her painting materials, and her father, a philosophy teacher, would bring her art books from his trips to France. However, they changed their tune when she expressed a serious desire to take the academy’s entrance exam. Instead, they enrolled her in a newly opened high school, falsely claiming that fine art was one of its key subjects.

Nevhiz’s reaction to her parents’ subterfuge not only reveals her determination, but also her strong stance in the face of injustice.

“I realized I had been deceived and decided to act. Whenever I was in the classroom during lessons, I folded my arms across my chest and refused to take notes or respond to any questions. This went on for a while. My mother had said I should become a chemist and paint as a hobby. Coincidentally, it was the chemistry teacher who had had enough. She asked me to leave the classroom — and I never returned,” she explains.

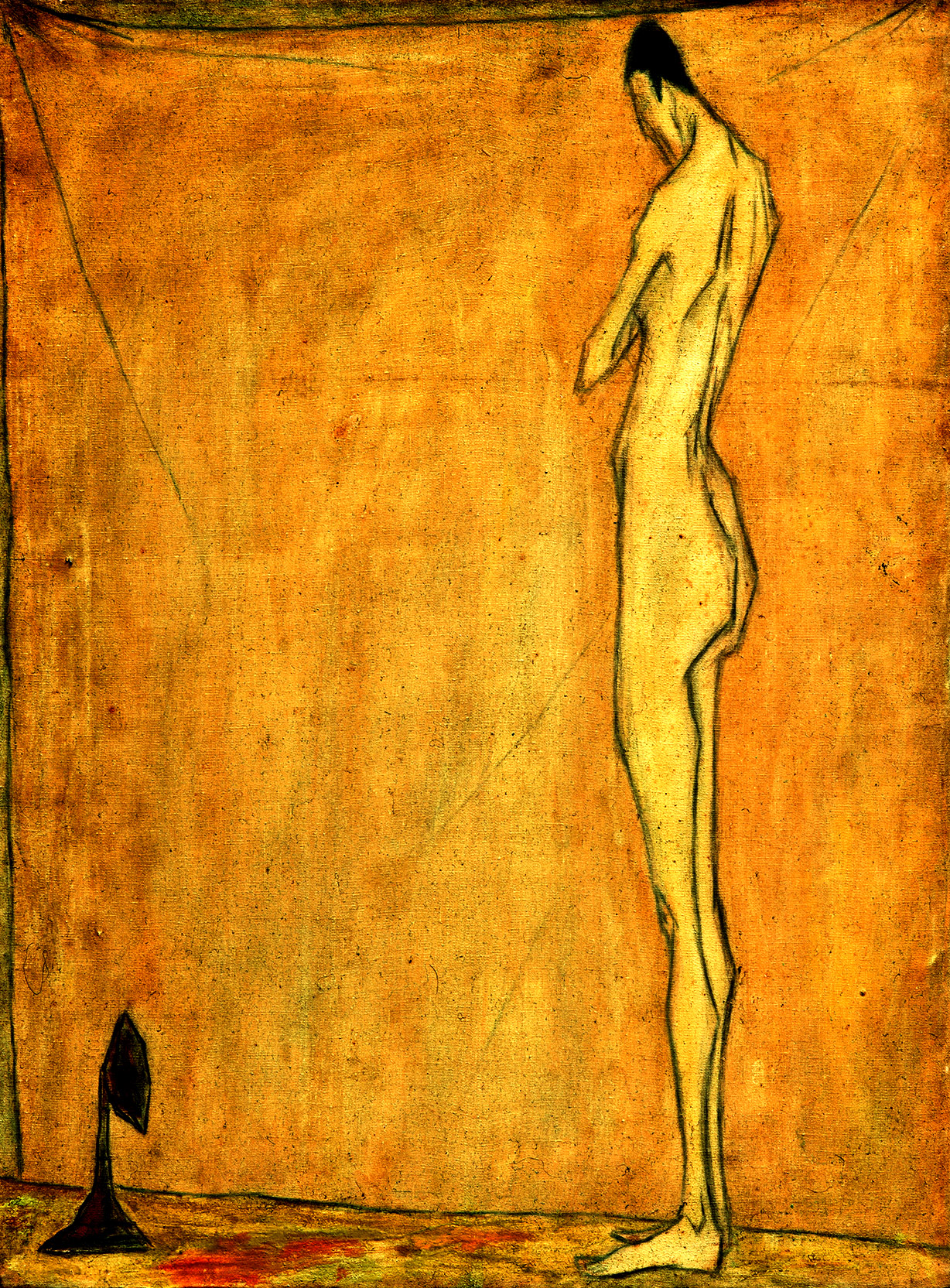

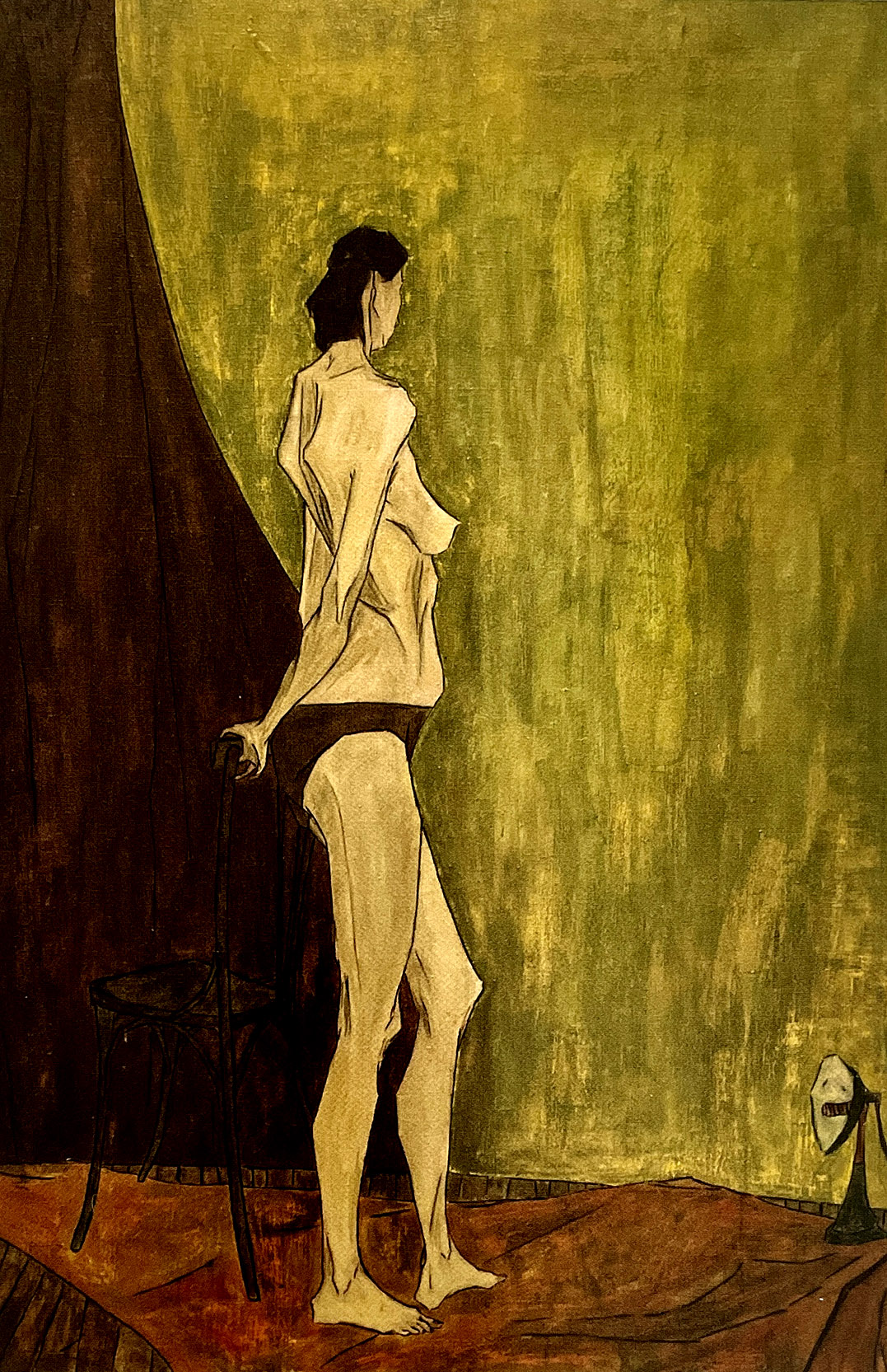

Nevhiz entered the academy the following year. Her work from this formative period (1959–1965) consists largely of nudes with strongly outlined, elongated limbs, rendered in earthy tones. These early pieces already show notable confidence and maturity for a developing artist.

In her second year at the academy, she was introduced to the poetry of Nâzım Hikmet. Stripped of his Turkish citizenship for his pro-communist views, Hikmet was then living in exile in the Soviet Union, where he would die in 1963. His work remained banned in Turkey for many years to come. One day, a friend of Nevhiz’s — whose family was involved in publishing — appeared at school with a bundle of hand-typed copies of Hikmet’s poems.

“There’s a conference hall at the academy. When there’s no event, the lights are usually off and the curtains drawn. I got to know Nâzım for the first time by reading his poetry in that dim place, and I was deeply moved. I later did six small drawings based on one of his poems, ‘The Epic of Sheikh Bedreddin.’ Getting to know Nâzım opened a whole new horizon for me,” Nevhiz recalls.

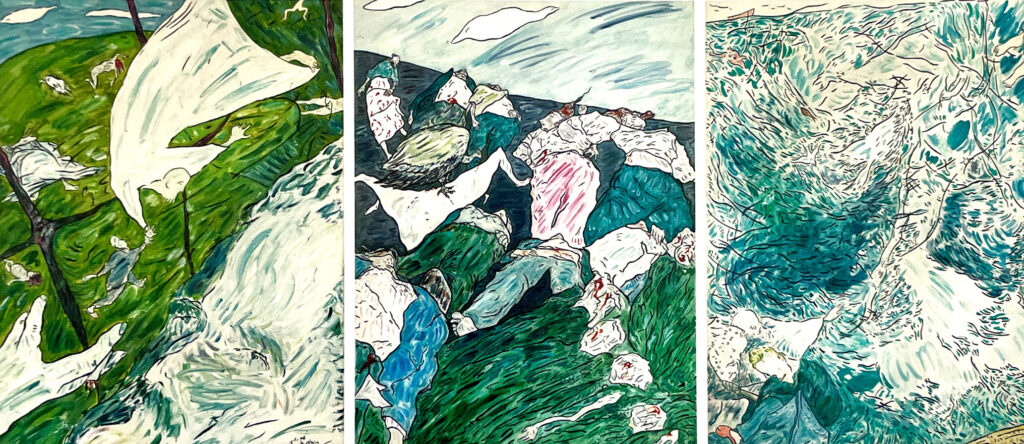

Sheikh Bedreddin — an influential fifteenth-century mystic, scholar, and theologian — was executed for leading one of the earliest revolts in the Ottoman Empire. Hikmet’s poem popularized Bedreddin as a historic symbol of socialism and resistance to tyranny, making him a powerful figure for Turkey’s left. Nevhiz’s Sheikh Bedreddin series opened the way to a broader body of work exploring collective traumas — massacres, assassinations, and other manifestations of political violence against the leftwing in Turkey, in the ‘70s and beyond. Years later, in 2006, while living in Paris, the artist revisited the poem through a large triptych.

Politics Over Art: The Workers’ Party Years

The 1960s saw the rise of the Workers’ Party of Turkey (TİP), the country’s first socialist party to gain parliamentary representation. It was founded shortly after the 1960 military coup, which overthrew a democratically elected government and led to the execution of the prime minister and two cabinet members.

TİP emerged from the egalitarian atmosphere fostered by the 1961 constitution, the country’s shifting social structure, and a growing wave of global leftist movements. It drew support not only from the working class but also from students and intellectuals.

Aged twenty-one, while still a student at the academy, Nevhiz married the renowned author and editor Feridun Aksın. Through Aksın’s connections in Turkey’s literary circles, the couple frequently socialized with well-known writers and poets such as Sevim Burak and Tomris Uyar, as well as Cemal Süreya and Edip Cansever — both pioneers of the Second New Movement in poetry, a 1950s–60s literary trend characterized by experimental language, explorations of interiority, and a rejection of overtly political or social themes.

“When Edip wrote a poem, he would first ask Feridun to read it,” Nevhiz recalls.

Only decades later, from 1990s onwards, would she commemorate this special period by painting portraits of many of those figures. Following her graduation from the academy in 1965, she and Feridun became active members of TİP. It was a time in her life when politics took precedence over art.

My paintings are like my diary — diaries of my life and of Turkey. Sometimes the two overlap.

“I became quite the militant and decided that raising awareness among women was more important than painting for myself. So, I forbade myself to paint. Feridun eventually became head of the party’s Beyoğlu district [in Istanbul], and I became the head of the women’s branch there. We were very active, constantly in meetings. When we left the headquarters at midnight, there was a beerhouse nearby. We would go there with the board members; we’d drink beer, and the meetings would continue there. After a while, the instinct to draw started prodding me again. I slowly began carrying a notebook and pen in my bag. I’d draw while others talked. That became a very productive period for me,” she explains.

“How so?” I ask.

“I became freer,” she replies.

“In what way?” I press.

“I began to develop my own [visual] language — one very different from that of the academy,” Nevhiz says after a brief pause, her tone reserved. While she’s open and generous when speaking about her life, she remains guarded when it comes to her art, offering little beyond the bare minimum — adamant that people should form their own conclusions.

The late 1960s and early ‘70s were especially turbulent times in Turkey. Escalating clashes between left-and right-wing groups, combined with economic hardship, led to widespread unrest and, eventually, another military intervention in 1971. TİP was banned, and a wave of state repression followed.

“They started rounding up all the members of the Workers’ Party and imprisoning them. They started killing the youth. I had received a four-year government grant to study in Paris.* It was such a critical time — we were so worried they would nail us that we couldn’t even go to collect our passports. Instead, we arranged a firm to do it on our behalf.”

First Visit to Paris and Her Political Paintings

In Paris (1971–1975), Nevhiz cherished seeing the original works of world-renowned painters.

“I went to the exhibitions of Vincent Van Gogh, Otto Dix, and others. It was very good for me. Also, whenever I used to go out in Istanbul, I would be pestered by men. As a young woman, for the first time, on the streets of Paris, I had the freedom to smile at a tree and observe it,” she tells me.

During this period, Nevhiz also visited galleries and museums in London and Madrid and later conducted a survey on Francisco Goya’s paintings. Her four years in Paris was a highly productive time — one in which she found her artistic voice and reached a certain level of maturity.

A vibrantly colorful and dynamic approach — already visible before she left Turkey — came into full bloom. In these works, forms became fluid and expressive, while lines conveyed movement and psychological tension, a quality that would remain central to her art.

Although life in Paris exposed her to new artistic experiences, she was still deeply affected by the political upheavals in her homeland.

“Turkey was always on our minds. We were constantly receiving news about the latest developments. Sometimes they were funny. Like [the famous poet and renown boozer] Can Yücel being thrown into solitary confinement. Why? Because he was caught making wine with grapes!” she reflects with humor.

But not all the news carried such levity. On March 30, 1972, a group of leftist militants led by twenty-six-year-old Mahir Çayan took three foreign NATO technicians hostage in the village of Kızıldere in northern Turkey. The abductions were intended to halt the executions of Deniz Gezmiş, Yusuf Aslan, and Hüseyin İnan — three members of the People’s Liberation Army of Turkey (THKO), all in their early twenties, who had been sentenced to death for attempting to overthrow the constitutional order.

Turkish security forces surrounded the house in Kızıldere, and a shootout followed, leaving the three hostages and ten militants, including Çayan, dead. On May 6, 1972, Deniz Gezmiş and his two comrades were executed by hanging in Ankara. Both events marked a turning point in Turkey’s history and remain an open wound in its collective memory.

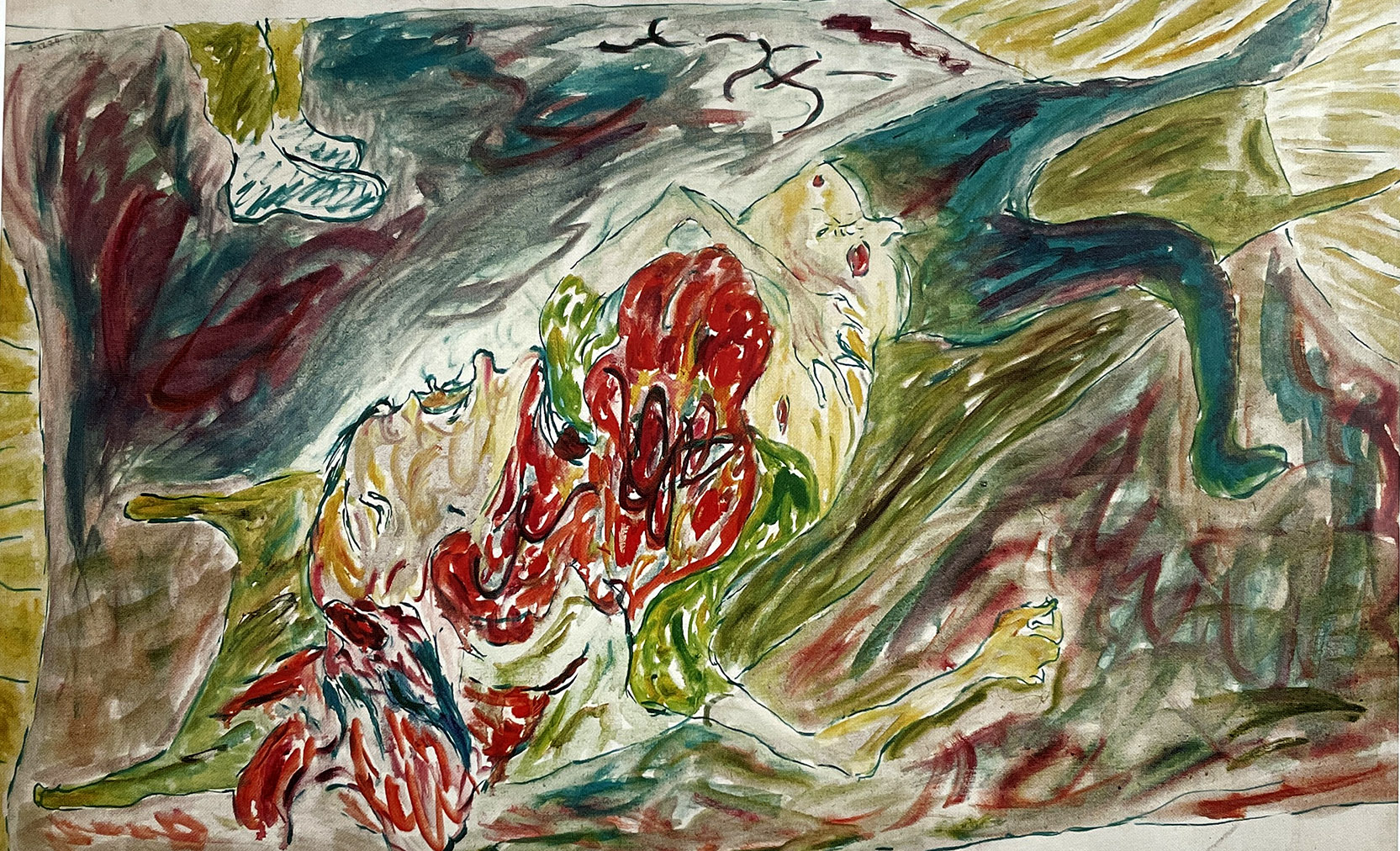

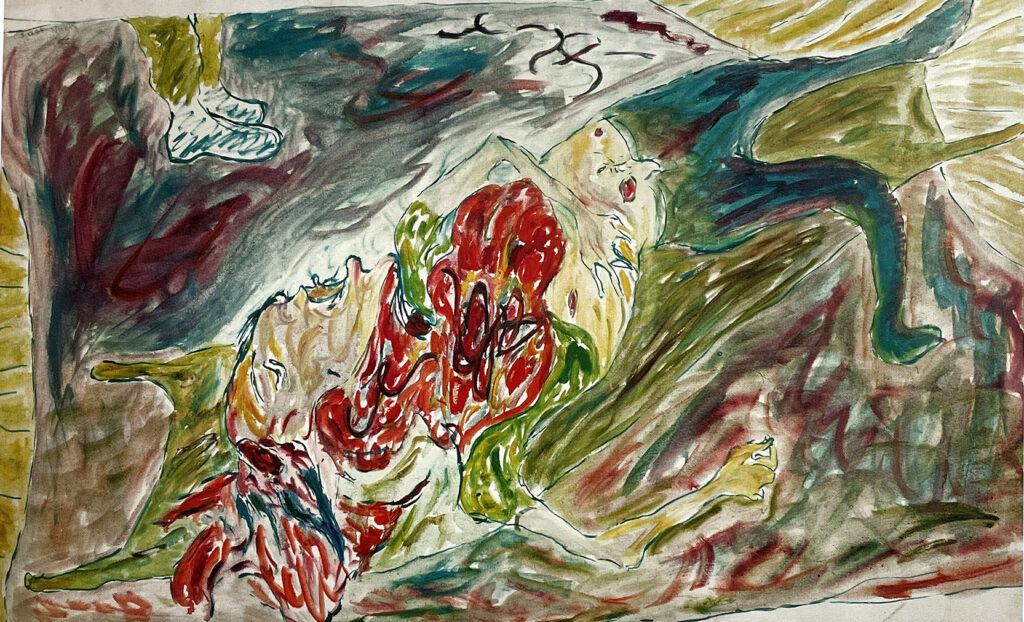

That same year in Paris, Nevhiz created a work titled “Kızıldere,” depicting several dead bodies, their chalk-white skin flecked with scarlet dabs, floating in a murky, ominous ground. Two years later, in “Sleep, Fly and Rest: Even the Sea Dies,” the reclining body of a leftist militant who received multiple fatal chest wounds during another raid was her subject.

In both works, the partial presence of a pair of boots suggests the unseen witnesses — or perpetrators — of the killings.

In “Sleep, Fly and Rest: Even the Sea Dies” (above), its title taken from a Federico García Lorca poem, an outburst of unrestrained reds illustrates the fatal wounds of the young Marxist revolutionary Hüseyin Cevahir — a co-founder of the People’s Liberation Party Front of Turkey (THKP–C), who was killed by security forces on June 1, 1971, during a police siege in Istanbul, following a hostage standoff. He was not unfamiliar to Nevhiz, who had encountered him at various political gatherings while still in Istanbul.

Sacrificing Artistic Freedom for Accessibility

At her first exhibition in 1977, held in Ankara soon after her return from France, most viewers mistook the red scribbles in “Sleep, Fly and Rest: Even the Sea Dies” for flowers — a misreading that prompted a major shift in her artistic approach.

“Just like I had forbidden myself to paint while I was at the Workers’ Party, this time I decided to paint in a language people would understand — where they wouldn’t mistake a murdered youth for a flower. It was more realistic, but it wasn’t me. I had limited myself again.”

By 1978, newly divorced and raising her ten-year-old son Mehmet alone, Nevhiz began her academic career teaching painting at what was then the Atatürk Faculty of Education, now part of Istanbul’s Marmara University. At the time, schools and universities across Turkey had become hotbeds of political unrest, with violent clashes between right- and left-wing groups erupting on many campuses.

“Students and teachers were being killed. The day I arrived there they had planted a bomb in the head teacher’s office. A corridor had been demolished. The dorm for the Grey Wolves was just across from the campus. Once, they put a bomb under another teacher’s desk. Pieces of his brain were collected from the floor below. Students’ arms had been mutilated. It was that kind of period. Over time, things calmed down. Then came the 1980 coup,” Nevhiz recounts.

Years later, she would poignantly portray the art historian and poet Bedrettin Cömert — his head flung back, a bleeding gunshot wound beneath his chin. He was assassinated by ultra-nationalists in Ankara on July 11, 1978, after setting off in his blue Volkswagen with his Italian wife, Maria, who, though severely wounded, survived the attack. The previous year, Cömert’s Turkish translation of Gombrich’s The Story of Art had won a major literary translation award in Turkey.

By the 1980s, with her intention to “paint in a language people would understand,” a more legible narrative began to dominate her art — a tendency that continued for about a decade. Yet despite this shift, Nevhiz never fully gave in to conventional norms of representation. Her work captured acts of political violence and workplace accidents, not in full view, but through fragmented close-ups and distorted angles — like the lens of a camera left behind at the scene of a crime — charged with the unsettling suspense of whatever lay just beyond the frame.

Erkan Doğanay, the curator of her 2020 Istanbul retrospective, The Odd Song of My Existence, observes, “Nevhiz herself is caught in a tension between the act of creation and what it reveals — a tension her work compels the viewer to share. These snapshots are, in fact, a way of reading history: the artist reading history through her own process, through her own experience. When one engages with them, they can feel deeply disturbing. They ask the viewer, ‘Where do you stand?’ They draw the viewer into an uncanny space, propelling them to question their own existence.”

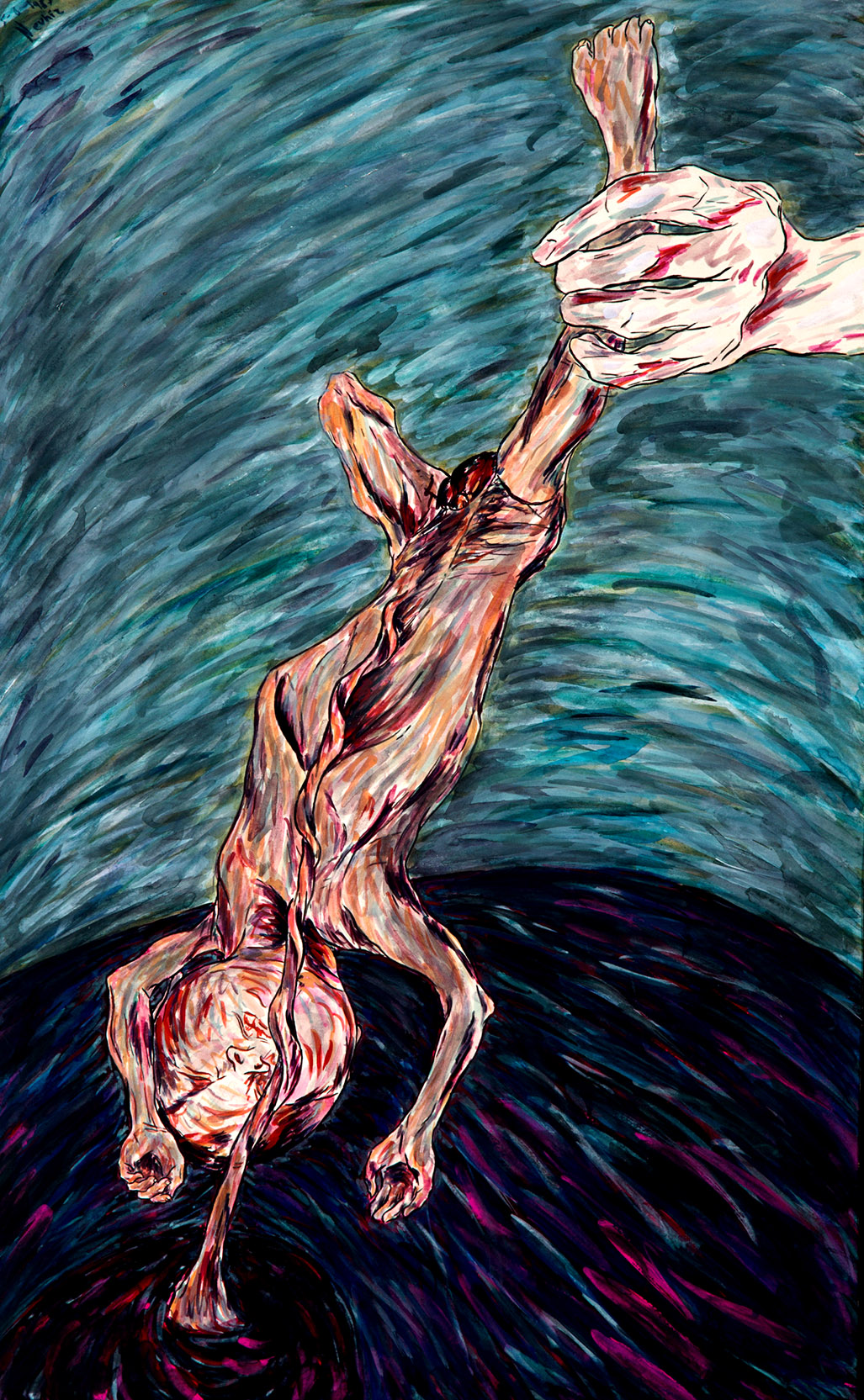

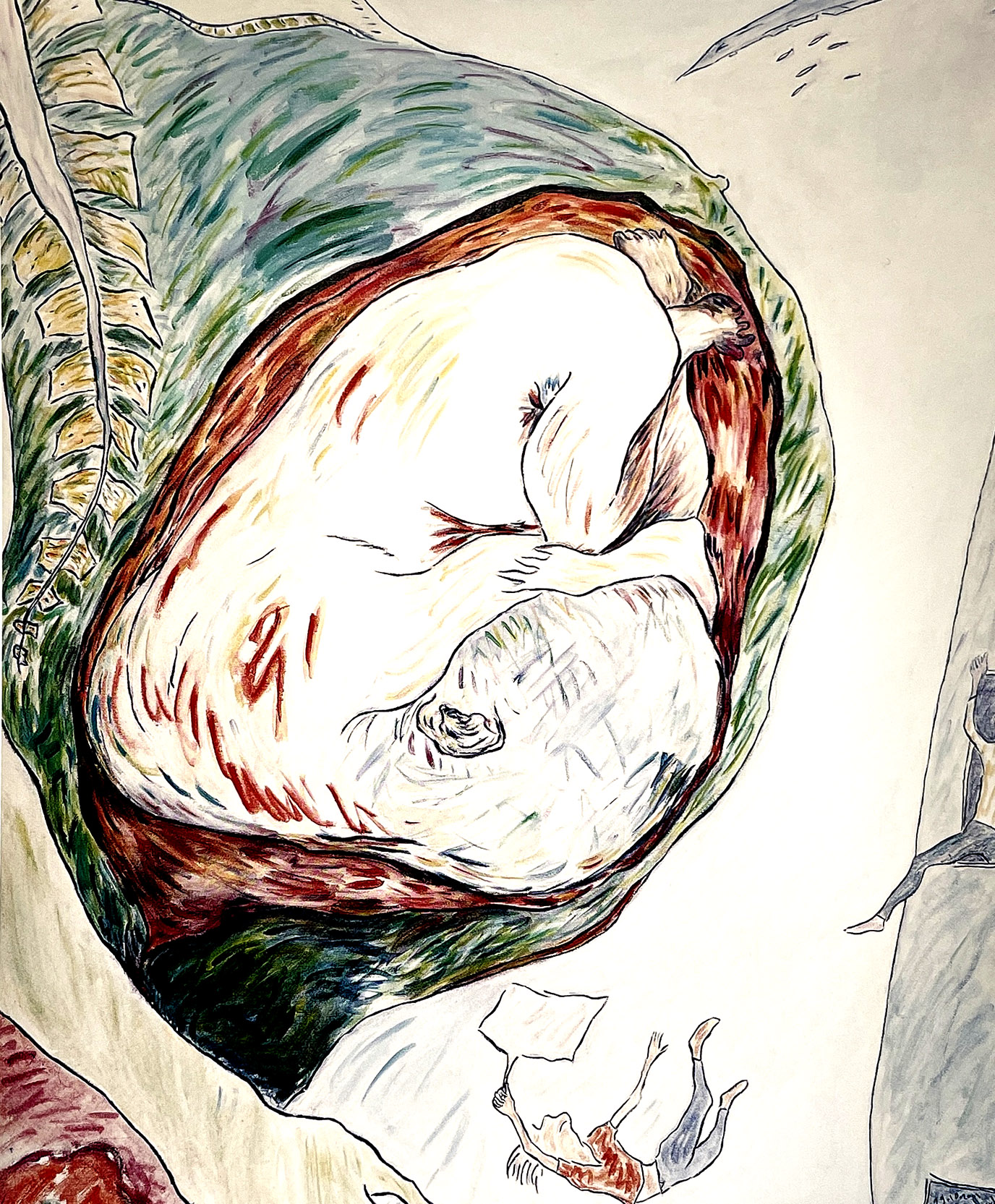

In 1983, she painted a newborn baby, its umbilical cord still attached, held upside down by one foot in a surgeon’s hand. The title “Kubura” — meaning “into the soil pipe” — alludes to the idea that every baby, from the moment of birth, is delivered straight into the pit of the system.

The spiraling vortex of lines around the infant’s frail, bloodied body conveys the apprehension surrounding the raw, gory reality of childbirth. Over the decades, the artist would return to the themes of birth and pregnancy, approaching these subjects with similar visceral intensity.

Doğanay points out, “She uses the brush almost like a pencil. She’s not someone who enjoys heavily layered paint; her use of color is more thinned out and economical. That’s why contour holds such significance in her compositions.”

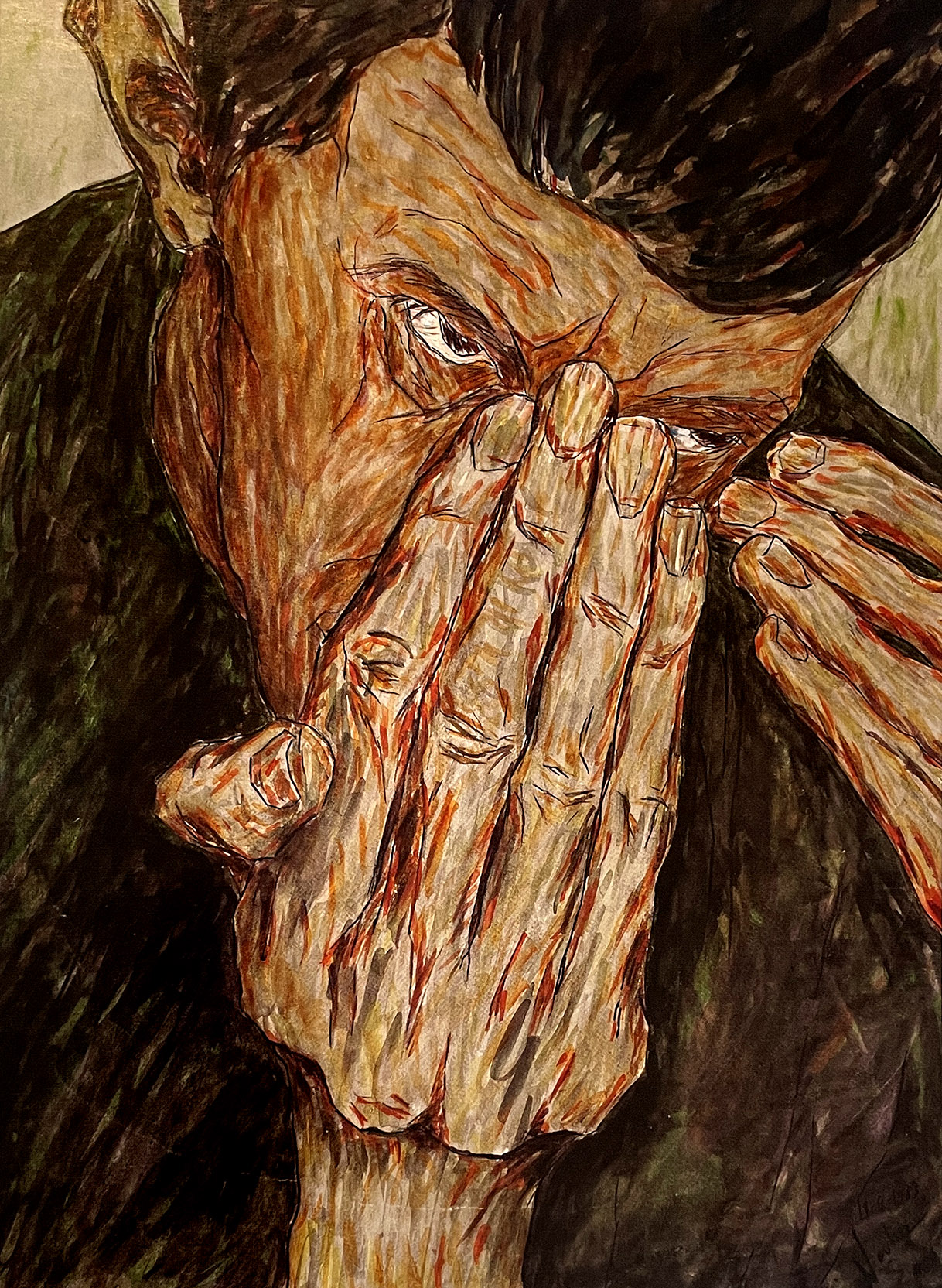

In keeping with the grimness of her subjects, Nevhiz’s palette grew increasingly stark over time. In her intimate portraits, faces bear life’s emotional toll. In a series of other paintings, she portrayed individuals in moments of deep anguish — something I bring up during our interview.

“In your works, particularly from the ’80s and early ’90s, we see figures shielding their faces.”

“They don’t want to face reality,” she says.

“Some seem to be screaming in agony or are caught in gestures that suggest an inner struggle or crisis. Why do you gravitate toward such subjects?” I ask.

Nevhiz pauses, takes a drag from her cigarette, and then replies: “It’s to do with the things I experience. My paintings are like my diary — diaries of my life and of Turkey. Sometimes the two overlap.”

Tortoises: Path to Liberation

In the early 1980s, her son kept two tortoises in an aquarium. Nevhiz often watched them closely and made sketches. But it wasn’t until the 1990s that tortoises began appearing in her paintings, initially perched on top of a reclining female nude, like Zeus in disguise. These erotically charged, enigmatic compositions, in which warped perspectives generated a fraught tension between surfaces and forms, marked a new chapter in her work: a freer, more uninhibited mode of expression.

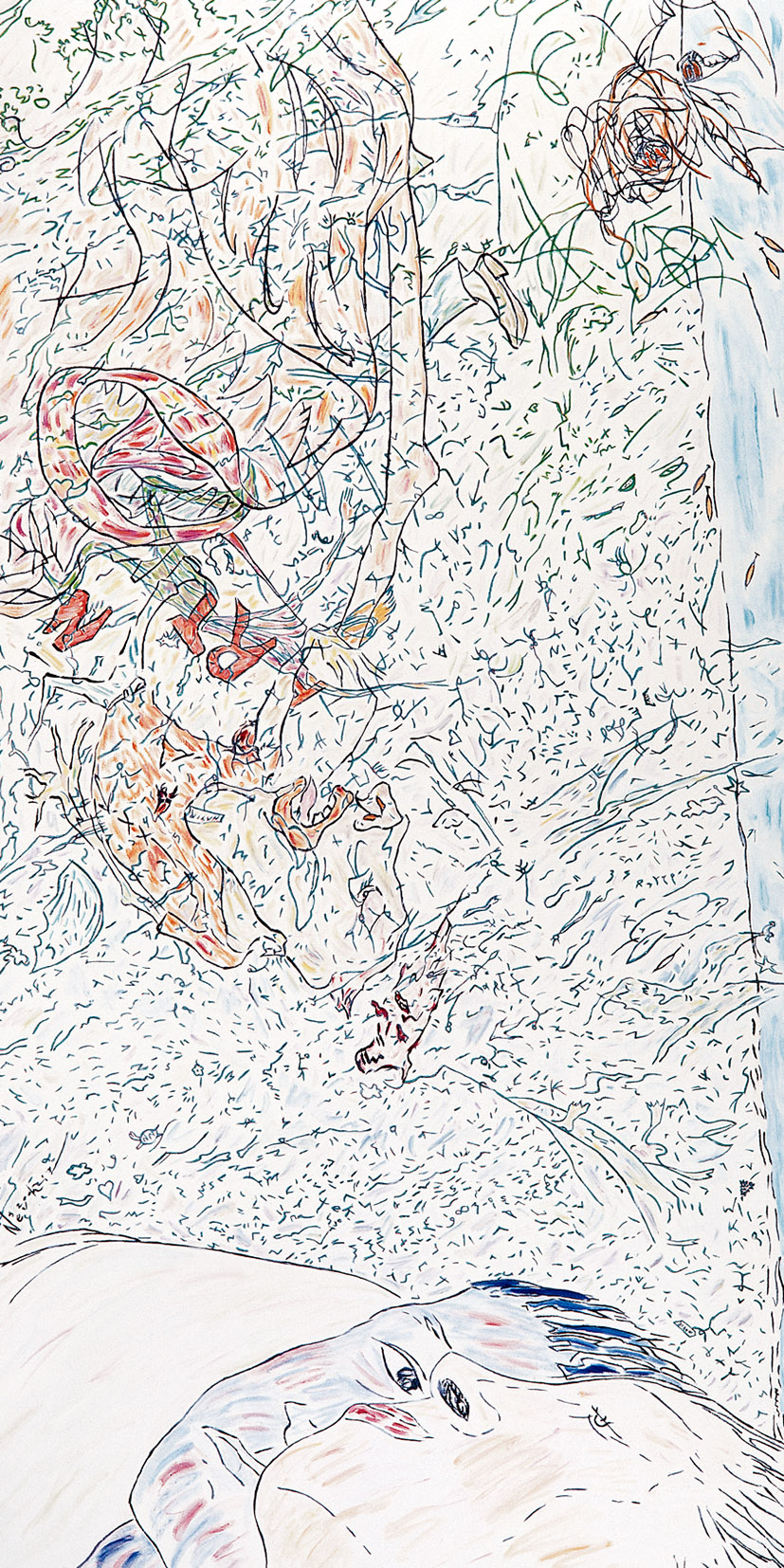

By the end of 1999, after a two-year stint as Dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts at Mersin University, Nevhiz finally retired from academia. “Ahh, freedom!” she exhales, recalling the moment. This sense of liberation is evident in the work she produced thereafter. Instead of making art that could be more easily deciphered by others, following her intuition, she ventured further into the untrodden terrain of her subconscious.

Scrawny figures leapt out of nowhere and floated freely in the air, while behind them, buildings seemed on the verge of collapse. Some dangled playfully from a thin branch — beneath them, perhaps, an endless abyss. Nevhiz often tilted the central axis of her compositions, subtly heightening the sense of unease.

Figures were sometimes cramped at the edge of the compositions, or else appeared to be nightmarishly free-falling through a space where any sense of up or down had dissolved. On the narrow, vertical canvases she began working on more frequently during this period, there was at once too much space and not enough. Even contour — a defining element of her pictorial language — disintegrated into minute, squiggly gestures.

When I ask the artist if she ever had an interest in venturing into abstraction, she responds assertively: “No. But every figurative painting has abstract elements. They are two parts of a whole. For a painting to be good, this is crucial. Figurative painting isn’t merely about depiction.”

Paris Second Time Round

After her retirement Nevhiz began making frequent trips to Paris to visit her son Mehmet Aksın — now a cinematographer living in the city — and to help care for her grandson, Sacha, who had just started secondary school. In 2004, she rented a studio in the suburb of Montreuil, and spent the next ten years living and exhibiting in Paris, where she would revisit Nâzım Hikmet’s poem “The Epic of Sheikh Bedreddin,” this time with a large tryptic which showcased her diverse narrative range.

On December 28, 2011, near the Turkish–Iraqi border in Şırnak Province, a group of Kurdish villagers returning from a smuggling trip were bombed by Turkish military aircraft, reportedly due to intelligence that mistakenly identified them as PKK fighters. Thirty-four people were killed, many of them teenagers. When Nevhiz later depicted this tragic event — known as the Roboski massacre — in her Paris studio, it is worth noting that, in contrast to her freer style from that period, she returned to a more conventional narrative approach.

After she began experiencing knee problems and found it difficult to get around Paris (she mentions that some underground stations lacked functioning lifts), Nevhiz moved back to Turkey for good in 2014.

When our conversation finally turns to her return to Istanbul, she leans back on the sofa, sighs deeply, and says she’s quite exhausted from talking — then lights another cigarette. In her defense, she’s been speaking about her life for nearly two hours, and I’ve been seizing every opportunity to ask about her paintings.

“I only have a few more questions,” I reassure her. “Just a few basic ones. For instance, do you prefer to work in oils?”

“In oils, acrylics, ecoline, watercolors, pastels — whatever I have at my disposal,” she replies. “Sometimes at a dinner table, if I have nothing with me, I use cigarette ashes and olive oil.”

“How long does it usually take you to finish a painting?” I ask.

“Depending on the painting, sometimes several days, sometimes a single day. In the past, I used to work up to sixteen hours a day. These days, after only two hours, my back begins to ache. Of course, the machine has aged,” she adds with a laugh.

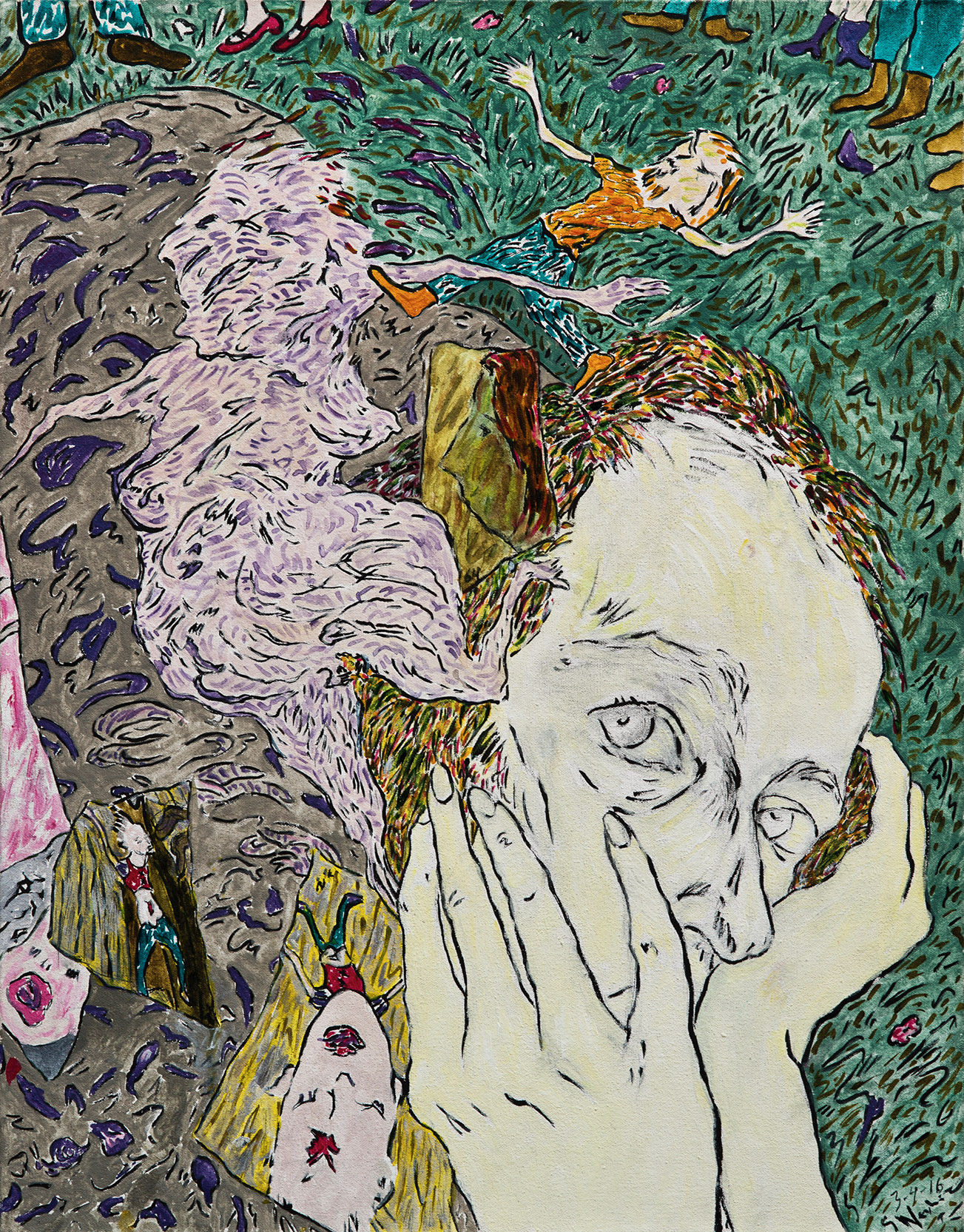

The Selves of Nevhiz

Among the works Nevhiz produced in Istanbul during the latter half of the 2010s are several self-portraits. What immediately stands out is the variety of styles she adopted to explore the self — from the illustrative to the cartoonish, at times verging on the grotesque or self-mocking. In some, she gazes directly at the viewer with a piercing stare; elsewhere, her expression is glum, a black cloud hovering above her head as she paints a screaming man — his wide-open mouth like a vortex, a recurring motif in her work.

Other recurring motifs also haunt these self-portraits — forms that have become part of her visual lexicon: a tortoise; a young man with multiple gunshot wounds lying on a stretcher; the boots of a soldier or policeman. In certain works, the single pair of boots is replaced by multiple feet — male and female — presumably those of viewers who observe, judge, and bear witness to her paintings.

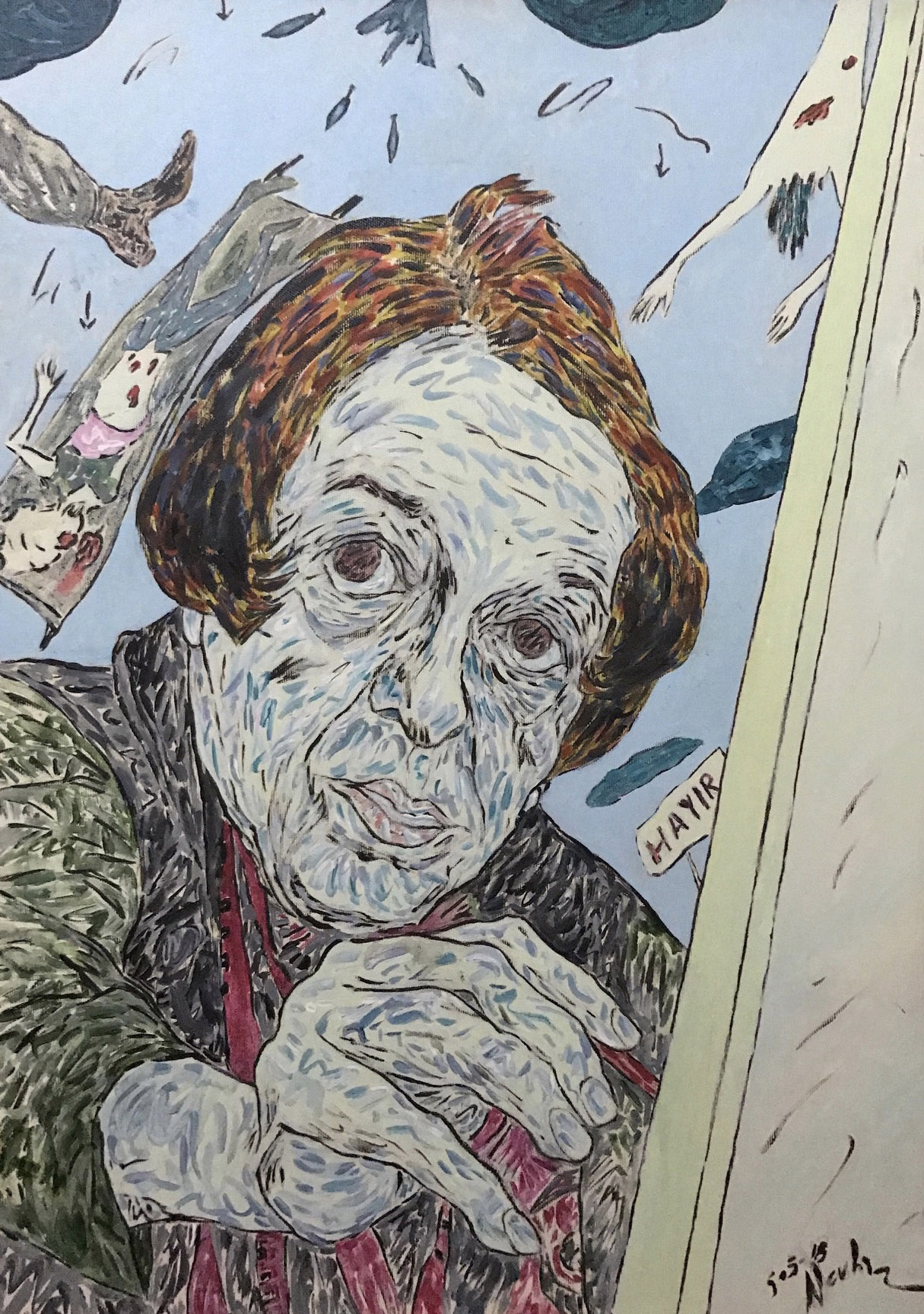

In “Burlesque” (2018), her naked, deformed self — another recurring image — stands before a blank canvas, her body covered in squiggles and stains, as if melting into the animated pattern that fills much of the composition. In “Nevhiz” (2018), a placard beside her bears the word “Hayır” (“No” in Turkish).

Later, as we leaf through one of her exhibition catalogues, we come across this painting. “This must be a direct reference to the 2017 referendum,” I say.

The constitutional referendum, brought forward by the ruling AKP government and its ally, the MHP, proposed sweeping changes — including the abolition of the prime minister’s office and the centralization of executive power in the presidency — which effectively transformed Turkey’s parliamentary system into a presidential one. The proposals passed with a narrow majority of Yes votes, marking a divisive moment which concentrated power in the presidency and significantly weakened Turkey’s democratic institutions.

“It’s a No to the system and to what it brings,” Nevhiz replies defiantly — still a rebel at heart, yet suggesting that her art grapples with forces larger than contemporary politics.

Since our interview, Nevhiz has moved to Fethiye, where she is working on a new series of paintings.

Nevhiz (aka Nevhiz Tanyeli) was born in Edirne in 1941. In 1965, she graduated from the Department of Painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul. During her studies, she trained in the workshops of Neşet Günal, Cemal Tollu, and Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu. In 1971, she was sent to Paris under Law No. 1416, which supported the education of future academics for universities and academies. There, she received training in several disciplines: painting in the studio of Gustave Singier; lithography with A. Haddad at the École Nationale Supérieure’s Plastic Arts and Painting School; stained glass in the workshop of R. Gireux at the School of Applied Arts; and engraving in the studio of Richard Licata at Académie Goetz. She later carried out research and surveys on painting in museums and galleries across France, England, and Spain, including a study on Goya.

In 1978, Nehviz began teaching in the Department of Art Education at Istanbul’s Atatürk Faculty of Education. When the faculty was reorganized as the Atatürk Faculty of Education under Marmara University, she continued teaching in the Department of Painting, and later in the Faculty of Fine Arts. From 1985 to 1997, she served as the Head of the Art Department at the Atatürk Faculty of Education. In 2003, she faced a major setback when most of the works for her first retrospective were lost during preparations at a gallery in Istanbul. Later that year, the exhibition was successfully restaged under the title Painter of Provocation: Nevhiz Tanyeli at the Milli Reasürans Gallery in Istanbul. She received the Sedat Simavi Award in 2013, and in 2014 was honoured with the TÜYAP Artist Honour Award. Her second retrospective, The Odd Song of My Existence, was held in 2020 at İşbank Kibele Art Gallery, Istanbul, and then in 2022 at İşbank Museum, Ankara.

Select Solo Exhibitions

1964 – The Art Gallery of Istanbul Yacht Club, Istanbul

1964 – Taksim Art Gallery, Istanbul

1970 – Taksim Art Gallery, Istanbul

1977 – Ortadoğu Art Gallery, Ankara

1983 – Caddebostan Art Gallery, Istanbul

1983 – Öztatar Art Gallery, Istanbul

1984 – Taksim Art Gallery, Istanbul

1984 – Atatürk Art Gallery, Istanbul

1984 – Mungan Art Production Gallery, Ankara

1987 – Taksim Art Gallery, Istanbul

1987 – Atatürk Art Gallery, Istanbul

1988 – Altıneller Art Gallery, Istanbul

1992 – Kadıköy Culture and Art Centre, Istanbul

1995 – Art Gallery of Casa Pera Art, Istanbul

1997 – Maltepe Art Gallery, Istanbul

2000 – Parmakkapı Art Gallery, Istanbul

2003 – Painter of Provocation: Nevhiz Tanyeli, Milli Reasürans Art Gallery, Istanbul

2004 – Portes Ouvertes des Ateliers d’Artistes, Montreuil, Paris, France

2005 – Portes Ouvertes des Ateliers d’Artistes, Montreuil, Paris, France

2006 – Portes Ouvertes des Ateliers d’Artistes, Montreuil, Paris, France

2007 – Portes Ouvertes des Ateliers d’Artistes, Montreuil, Paris, France

2008 – Hand-in-Hand Culture Centre, Paris, Fransa

2008 – Portes Ouvertes des Ateliers d’Artistes, Montreuil, Paris, France

2009 – Portes Ouvertes des Ateliers d’Artistes, Montreuil, Paris, France

2010 – Portes Ouvertes des Ateliers d’Artistes, Montreuil, Paris, France

2014 – Nar Artiz Gallery, İzmir

2014 – The Sleeping Beauty, Gallery Nev, Ankara

2018 – I Have Seen Evil, Corpus Gallery, Istanbul

2020 – The Odd Song of My Existence, İşbank Kibele Art Gallery, Istanbul

2022 – The Odd Song of My Existence, İşbank Museum, Ankara