Noir is less a genre than a lens: a way of seeing the world — and especially today's world — through shadow and smoke.

We all at one time or another grapple with noir, dark moods and alienation, bordering on depression. The French have an idiom for this negative state of mind — “le cafard” (the cockroach). When you say j’ai le cafard, it’s akin to “I have the blues,” except that it in fact feels very dark, as if you’re trying to keep your head above water in a bottomless well. If you find yourself in such a state, the world can seem a small, confining space, not unlike the room in Sartre’s famous play, Huis clos.

It goes without saying that it can be hard to escape le cafard, to bring yourself back up to the light. Truth be told, none of us benefits from dark feelings of melancholy or depression in our daily lives, and yet in the literary world, there’s a cult around it, almost as if to write seriously, or to be taken seriously, you must be brooding and sad. In this editorial, I’d like to explore what it means to endure melancholy, to fight the cockroach as it were, by tuning in to what a number of writers have said about it. But first, I must confess that as a young writer, living in Paris in a fifth-floor walkup studio, I was happy in the gray, damp, cold weather — the grisaille — characteristic of the French capital, despite its moniker as “the City of Light.” “Earnest” and “serious” were the adjectives I would use today to describe my twenty-something self. Being in a melancholy mood seemed my daily bread, paired so aptly with the hidden sun, and the mostly glum faces of my fellow Parisians. In fact, I am certain I believed back then that the blues were the necessary mood for an artist or a writer at work, so much so that when I interviewed James Baldwin, I asked him (in the context of his lifetime of struggle as an African American writer who fought American racism, and coming to grips with the assassinations of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.): “Did you find it difficult to write then, or do you work better out of anguish?”

His response:

No one works better out of anguish at all; that’s an incredible literary conceit. I didn’t think I could write at all. I didn’t see any point to it. I was hurt . . . I can’t even talk about it. I didn’t know how to continue, didn’t see my way clear.

At the point at which I had these conversations with Baldwin (there were several, which wound up edited into one interview in The Paris Review), when he disabused me of the belief that the blues were a writer’s best friend, I was 24 years old. You’d think I would have turned the corner on embracing melancholy as a creative necessity, but then I went off to talk to Milan Kundera and Paul Bowles, both of whom had been influenced by Franz Kafka, nihilist of the absurd. Additionally, Kundera was a virtual disciple of the Polish master, Witold Gombrowicz, author of the classic dark novel Ferdydurke, while Bowles championed the work of Mohamed Choukri, in particular his tragic novel Le Pain Nu (For Bread Alone in Bowles’ English translation).

But just the other day, I heard the Moroccan novelist Tahar Ben Jelloun, in a podcast called Remède à la mélancolie (Melancholy’s Remedy), declare that he was “on the side of the light.” Previously, Ben Jelloun had declared himself a fan of Mohamed Choukri’s work, and had even written a few severely bleak novels himself, including Corruption (which I reviewed in its English translation) and This Blinding Absence of Light. In his conversation with podcast host Eva Bester, Ben Jelloun went on to say that he viewed melancholy in the same way he saw nostalgia, as almost sentimental, to be avoided. “[M]elancholia is defeat, a kind of withdrawal, a kind of sadness…I avoid it. When someone is melancholy, I try to make them laugh or dance to get them out of that state of sadness, which isn’t just sadness, but a kind of withdrawal from the world.”

Speaking on the same podcast, the late French novelist Philippe Sollers said, “Happiness is an act of courage,” and roundly criticized the notion that melancholia was a writer’s best friend. “I am resolutely hostile to melancholy,” he averred, and went on to quote French poet Lautrémont:

I replace melancholy with courage, doubt with certainty, despair with hope, malice with kindness, complaints with duty, skepticism with faith, sophistry with cool calm, and pride with modesty.

It occurs to me now that I have changed a great deal in the years since I lived in Paris and interviewed so many serious novelists. Back then, I was virtually obsessed with work that one could call gothic fiction, including Knut Hamsen’s Hunger, Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. I wore only black or onyx gray clothing, and I rarely joked or even cracked a smile. As noted above, I was earnest, intent on becoming a serious writer. To have depth meant you had to deal with your inner selves, which were inevitably conflicted, contradictory, and bound to make you moody.

Today, on the other hand, I am always searching for the light. I laugh easily, and joke often. I understand Jimmy Baldwin’s confession that anguish and pain and the blues were no recipe for being able to write deeply. That comes after the cafard, much later, when you’ve escaped the well and risen to the light.

•

While the cockroach no longer visits me with the intensity of my younger days, noir stories still arrest my attention. And the paradox here is strikingly clear: the French word noir translates to “black,” yet with a slight alteration in pronunciation, when adapted into Arabic, it becomes nawwar, meaning “that which radiates a great deal of light.” It is less a genre than a lens — a way of seeing the world through shadow and smoke, and every character is complicit in something. Morality blurs, truth is slippery, and every choice cuts. It speaks in terse dialogue and silence alike, always circling questions of guilt, fate, desire, betrayal, corruption, fatalism, and the cost of survival. In noir, the darkness isn’t just around us — it’s within.

Like a dark noir narrative, the world today feels increasingly absurd and nihilistic. Each morning, we’re confronted with unsettling images and videos that highlight the genocide in Gaza, a tragedy that has continued for over two years, alongside the drawn-out conflict in Ukraine. Meanwhile, we read statements from rightwing leaders and politicians whose views are astonishingly extreme. What’s truly alarming is that it seems as though they have collectively lost their minds — infecting the world like a sudden sneeze that spreads contagion. This is underscored by an avalanche of news regarding significant advancements in global armament, starting with drones capable of delivering lethal strikes anywhere, at any time; and by algorithms and AI, such that our lives are constantly surveilled.

All of this information comes to us through addictive screens that we hold in our hands or set on our tables, delivering information (and disinformation) with remarkable accuracy, quality, and speed. As we navigate our daily lives, we often experience tragic events just moments after they occur, creating a sense that we are actually living through them ourselves. Nowadays, many disagreements escalate into conflict, and many issues spiral into tragedy. As a result, feelings of uncertainty and anxiety are on the rise, and polarization deepens each day.

•

Given this context, we thought it fitting, for the closing issue of 2025, to choose the NOIR theme to address not only crime and punishment, but white-collar corruption, and a whole range of dark or difficult circumstances. For instance, in our centerpiece story “An Unwritten Poem,” Omar Khalifah writes of a Palestinian reader in New York City, who suddenly learns of the mysterious death of an acquaintance who shared a mutual appreciation for the late Palestinian poet, Mahmoud Darwish. In “Tuesday,” Majd Aburrub writes of a Palestinian in the Occupied Territories, stuck in his car at an Israeli checkpoint in sweltering heat (the wait to get to the other side is unbearable). In the story “A Never-Ending Day,” excerpted from the novel by Mohab Aref, in a translation from Arabic by Lina Mounzer, a low-level criminal named Magdy endures a chain of circumstances that are both violent and absurd. In “Tahmina,” a short story by Abdollah Nazari, translated from Persian by Salar Abdoh, the protagonist, after running her whole life — from war, exile, and financial hardship — can’t stop yet. Also from Iran comes Jafar Panahi’s Palm d’Or-award winning thriller, reviewed here by Alex Demynenko in “It Was Just an Accident: A Haunting Tale of Revenge.”

In “A Bomb for Personal Use,” excerpted from the eponymous Arabic novel by Mirna Al-Mahdi, and translated to English by Rana Asfour, this gritty, noir-tinged thriller interweaves multiple perspectives to explore exile, identity, resistance, and the human cost of war. An excerpt from Saïd Khatibi’s novel, meanwhile, The End of the Sahara, begins to tell the story of the end of socialism in Algeria, almost one year before the fall of the Berlin Wall. And we present the intense Kurdish poet Bejar Matur, who shares four poems from her collection, How Abraham Abandoned Me.

•

Does prison lead to writing? “Even if you’re not a writer at first, you start to write in prison in order to survive,” observes the late Ngugi wa Thiong’o, who wrote the foreword to a new anthology, Imprisoning a Revolution: Writings from Egypt’s Incarcerated, reviewed by Rebecca Ruth Gould in “The Price of Freedom: Prison Writings from Post-Revolutionary Egypt.” Also in NOIR, Melis Aker, a native of Turkey living in London, with her meditation “In Praise of Half-Light: Notes from a Gray City,” explores matters of light and shadows, and realizes, “Where I come from, that which is unseen is considered the truest and most beautiful of all.”

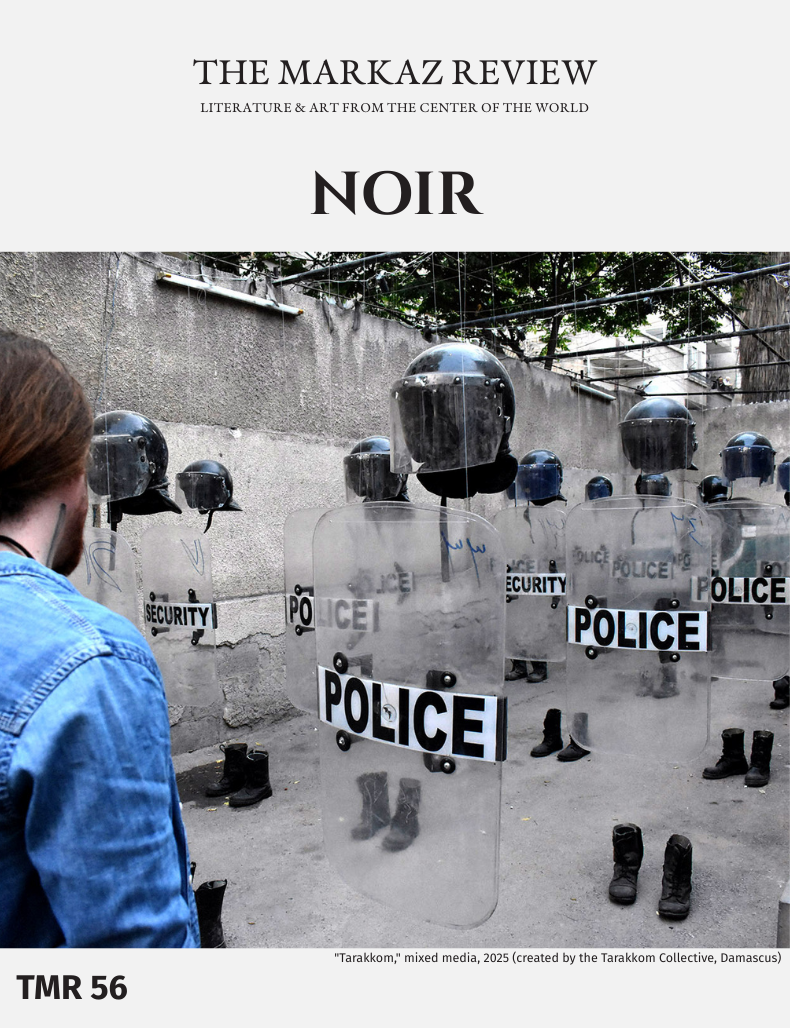

In “White Collar Noir: How John Roberts Corrupted the U.S. Supreme Court,” Stephen Rohde reviews a new book by Lisa Graves that recounts how extreme Republican judges have undermined the Constitution, threatening the democracy on which the United States was built. In “Pharmakon State: A Republic of Ruins, A Ritual of Return,” Damascus-based writer Robert Bociaga discusses an art exhibition filled with works that build upon trauma — art that asks Syria and the world, What happens after the collapse? NOIR’s featured artist, Ala Younis, a Kuwaiti of Palestinian heritage based in Amman, learned that in the Gulf, buildings were being torn down and rebuilt in 20-year cycles, due to the inclement weather conditions. These 20-year cycles fascinated the artist, and there is now a 20-year retrospective of her work on view, the subject of Arie Amaya-Akkerman’s essay, “Ala Younis: Ambiguous Architectures in Abu Dhabi.”

We round out the issue with recommended reading in “10 Noir Novels to Kill For,” along with “10 Noir Films from the Arab world, Iran, and Turkey.” What are your favorite noir stories? Let us know in the Comments sections at the very bottom of each post, or tell us about your favorite noir novels or films in our social media:

So this is a definition of “Noir”…seen through the lenses of various writers, artists and other creative people, a view of a world that sinking in extremism and racist, nationalistic violence, or American style…it’s all about the money and real estate deals devised by the T’s golf partners who are suddenly members of powerful war cabinets.

“What’s truly alarming is that it seems as though they have collectively lost their minds — infecting the world like a sudden sneeze that spreads contagion.” …..in your words, Jordan.

I don’t think Poutin plays golf, nor is he sneezing. He is leading a process that I believe will bring us to a third world war against the Europe that has reclaimed countries that were unwilling members of the Soviet empire. In the world of politics, it is a virus that may become more powerful every day, as others, the objects or victims of the virus, become weaker. It is not a sudden sneeze. This is why France and Germany are talking about re-instating compulsory military service. Sérieux.

Or is it an inside job, the torment that some believe necessary to write? Why don’t you ask your writers? And thank you for a positive evening here in Paris, not Noir. There was light on our faces and in our words. Because here, we are allowed to express ourselves. And I believe it is an inside job. To write creative short stories, poems, theatre pieces, song lyrics and so on, the Noir, the emotional torment, is a huge motivating factor, I believe, such as obsessive love for a partner….”don’t you love her as she’s walking out the door…” Do you know who sang it? I do.

But that Noir is not a motivating factor for a journalist writing a news piece, or a longer feature piece. Because torment or depression isolates us from the world around us. It puts up a transparent wall that allows us to see people, things and situations in the real world with which we are not interacting. I know this, yes indeed.