Select Other Languages French.

The third edition of the Festival du Livre Africain de Marrakech was seemingly presided over by the spirits of Toni Morrison and Angela Davis.

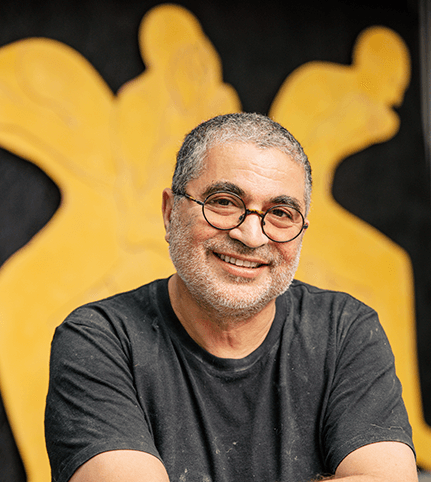

Like all the best ideas, it was simple — self-evident even — but somehow had never been attempted on this scale. The Marrakesh African Book Festival, or Festival du Livre Africain de Marrakech (FLAM), was intended “to talk about Africa from Africa itself,” explained Moroccan artist and writer Mahi Binebine. Only two years after its inception, it’s not unusual for FLAM, which is free of charge, to draw 8,000 participants. Participants and audience this year hailed from Cameroon, Congo, Chad, Djibouti, French Guiana, Haiti, Ivory Coast, Mauritania, Mauritius, Surinam, Togo, Tunisia, and Morocco itself, although many live and work in the United States or France, and everyone was speaking in French, the colonial mother tongue.

“Also,” said Binebine, laughing, “I was fed up of going to the other side of the world to meet my neighbors.” He has been criss-crossing continents and oceans — for exhibitions, book launches, festivals, and conferences, staying in whatever accommodation was offered — at least since I first met him, in 1999, so the comment was only half a joke. And it’s typical of his irony, revealing the patent absurdity of a situation I, for one, had given no thought to before. Back in 1999, when he was already well-established as a sculptor and painter, I first met Mahi Binebine as I was preparing to translate his book Cannibales into English (he is now completing his sixteenth, and at the Festival was discussing his most recent publication, La nuit nous emportera). The agonizing, wondrous novel I was about to translate back then — about a group of Africans attempting to cross the Strait of Gibraltar — was pointedly signed off East Hampton, 1999. Much of Binebine’s effort, outside of his artistic life — and, it could be argued, much within it — has been as social activist and innovator, his aim always to narrow the gap between these two worlds, the have-nots and the haves.

“We are all Africans.” It was a conviction, not a political idea, that might mend the links broken by colonization.

Fatimata Wane Sagne, whose humor and warmth are beamed across the continent for one hour every weeknight as presenter of Journal de l’Afrique on France24, which reaches 130 million people, explained to me: “We have the Dakar Biennale, the big book salons in Tunis, Algiers, and Marrakesh, and regional festivals…” But all these events are much smaller, and lack the funds to attract world-class writers such as Congolese writer Alain Mabanckou or Nobel prize-winning J.M.G. Le Clézio, for example. I had seen FLAM’s grand list of sponsors and asked Mahi how he’d managed to persuade these companies and institutions to fund the festival. “What can I tell you? I’m used to begging,” he said. I laughed, thinking of the array of beggar kids in his books, and of how, as one of seven children, he’d been brought up as much by Marrakchi medina streets and alleyways as by his mother, as his new book details. By now, of course, Mahi knows just about everyone in the city and can pick up the phone accordingly. “And we put up our writers in palaces!”

It was true: Es Saadi Palace Hotel resembles a mini-Taj Mahal. On the first night of this year’s FLAM, Mahi’s distinctive laugh heralded his arrival, high above the hum of lowered, first-night voices. Fatimata Wane Sagne took the microphone first to suggest that FLAM could be “a place to rethink, to dream the world otherwise.” She wondered, “How have we let these divisions — between Sub-Saharan, Sahelian, and Maghrebi, for example, let alone West Indian, Middle Eastern, American, or anywhere in the diaspora — separate us?” She answered flatly, “No. We are all Africans.” It was a conviction, not a political idea, that might mend the links broken by colonization.

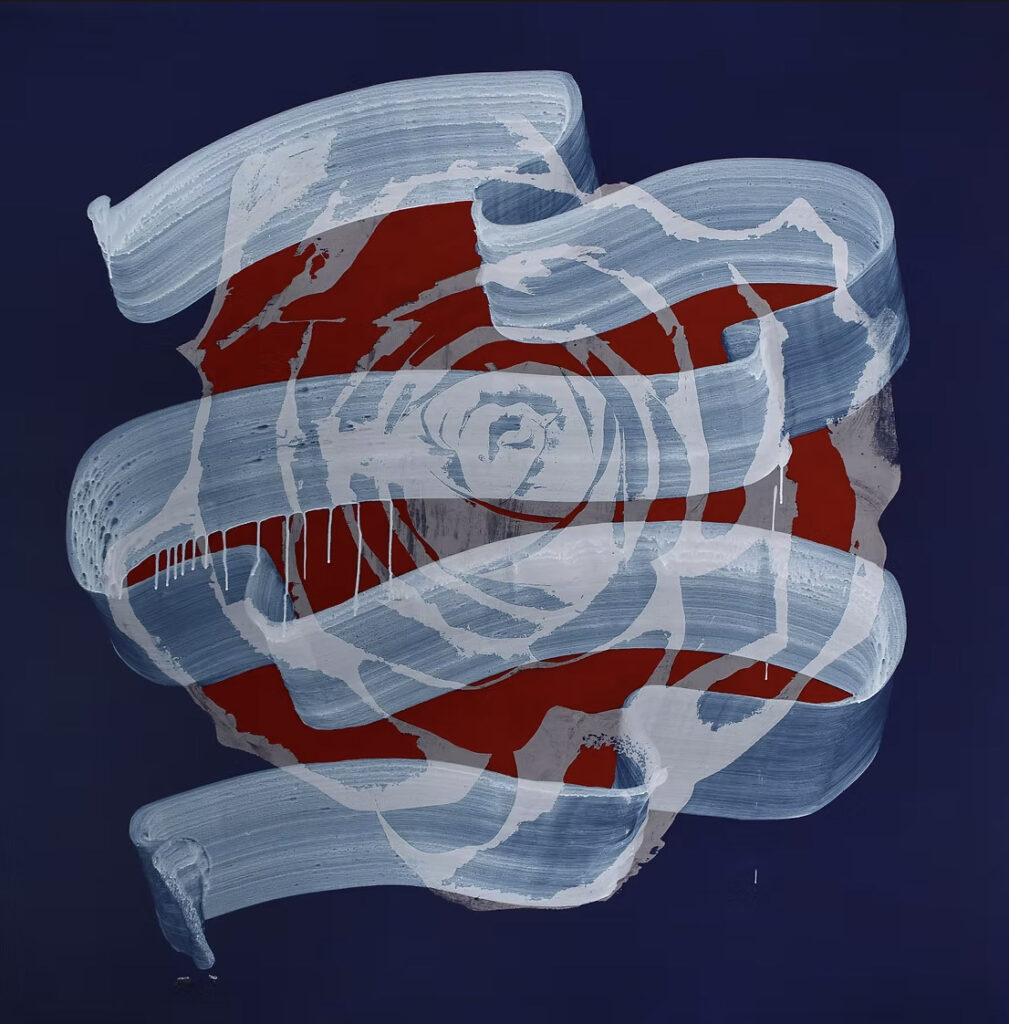

Next, Binebine recounted donating a huge painting he’d made to the Slavery Museum in Gorée Island, off the coast of Senegal. Too big to fit into the plane, it had had to travel all the way there in a lorry, but was too big even to enter the museum, which, as a UNESCO building, could not be touched to accommodate it. In the end, Binebine decided to have the work cut in two, even finding the exactly matching color of paint in a local market to cover the break. Now, he said, a Senegalese artist was proposing sending work to Marrakesh as an exchange, and so the story became a parable about Africa, about us all. “It’s hard to push, to get something through, but we can do it; we can find ways to build rather than destroy the world.”

What had I expected from a festival whose presiding spirits — to judge by how often their names were invoked — were Toni Morrison and Angela Davis (the latter rumored for a time to be coming in person)? It was as if on the flight over, reality had reconfigured such that what mattered to me mattered to everyone, in exact priority and proportion. As if my bookshelves had come alive. No, better than that — these were books and voices new to me. There were only six names I even recognized at this festival, only four I’d read. Or perhaps I’d dreamed up the whole thing just to hear what hope, if any, humanity could legitimately have at this moment.

FLAM kicked off with a panel on the power of the feminine imagination to reshape the world. Going by the fire of the women speaking, this was a mere matter of time. Battlers all, they were squaring up to the political moment; only Mauritian writer Ananda Devi’s face sometimes looked as stricken as I felt. Devi, whose work focuses on the most oppressed and vulnerable in society, had given the first address of the festival, “The Women Who Inspire Me,” the previous evening. That morning’s sudden downpour had meant the open-air of the riad of the Festival venue, the Centre Étoiles Djemaa el Fnaa, was swiftly vacated; damp and trickling with drizzle, we all relocated to the French Institute, on the outskirts of town, to an auditorium like a black felt box, that only amplified the women’s passion.

Devi raised the question everyone must have asked themselves recently, over and over: “What can we do, faced with climate, economic, and political crisis, with hysteria and racism, extremism and intolerance?” She shared her own bewilderment, wondering what any individual reader or writer could possibly achieve. “Maybe what I write can reach 10,000 people…”

“Literature does not change the world, but it changes people, who can,” was the rejoinder of Christiane Taubira, the former French Minister of Justice and a great emblem of women’s struggle, who was being honored at the festival.

“Christiane breathes strength into us all,” murmured Devi gratefully.

In 2021, Christiane Taubira fought for and instigated the French law that recognized slavery and the slave trade as crimes against humanity; she had also, along with Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, introduced the 2013 law enabling same-sex couples to marry and adopt children in France. Vallaud-Belkacem, the French-Moroccan Socialist politician who served as French education minister under President François Hollande, sat alongside Taubira now. She spoke of the women who had worked so hard to achieve independence in Morocco, who were “10,000 times more competent than the men” but who, when independence finally came in 1956, found themselves sidelined into charity associations, into lacemaking, as men slotted into the positions of power. Both women, of course, had stories of being sidelined and blamed while in office. “The moment there’s a crisis, a woman’s status as minister is instantly at stake, it’s nothing to do with the administration she’s working with, or anything else. They only see the woman… And often only her body, at that.”

Taubira took aim at the inherently hierarchical, supremacist nature of power. “It’s oppressive to men as well as to women, to comply with a structure that’s crushing them. We must take power, refuse to conform to normative expectations, and assert ourselves, without apology. […] I say it with my words, my body, my power: nothing’s impossible… And we must go on writing, in order to transcend our daily lives.”

“A world without women at the table means that we’re on the menu,” Vallaud-Belkacem interjected. “If we women don’t talk to each other, others will fill that silence; if there’s a lack of women’s stories, men will imagine they know what we want. […] The atmosphere in France right now is unbreathable; the colonial discourse has worked. We must stand together, not go alone. Because it is in the other that we meet ourselves.” Each called for much bolder, more courageous political action.

Ali Benmakhlouf, a professor of Arab philosophy and logic at universities in Morocco and Paris, paid an emotional homage to Aïcha Chenna, the Moroccan women’s rights’ activist who died in 2022 after ceaselessly battling on behalf of single mothers and children. “I don’t know why she’s not spoken about every day,” he said. In 1985, Chenna set up the Association de Solidarité Féminine in Casablanca, offering single mothers support and accommodation, classes in literacy, accountancy, sewing and cooking, and then a restaurant to work in. Undaunted by the continual threats and accusations leveled at her, Chenna spoke out relentlessly on taboo subjects in Moroccan society — abortion, rape, incest, prostitution — battling hypocrisy and Islamist traditionalists to the end, and calling for women’s emancipation from patriarchal structures and from domestic and reproductive roles. Benmakhlouf ended with a quote from Flaubert: “It’s the imagination that confers real tenderness.”

FLAM was enacting just such a vision. Alongside the writers’ talks and panels, the festival featured a program for young people, including a city-wide dictée, workshops, and university masterclasses; a benefit to fund the education of young rural women; and a daily “literary breakfast” with one of the festival’s featured writers and adolescents from the Centre Étoiles Djemaa el Fnaa. In the evenings, there were films, music, dance, and exhibitions of paintings and sculpture. This center, in whose courtyard we sat every day, had in fact come about through the tenderness and imagination of Mahi Binebine. After spending time in a shantytown outside Casablanca, Sidi Moumen, researching a book about the boys who were groomed to become the suicide bombers of the 2003 attacks on that city, which killed 45 people, Binebine had called on his friends and fellow artists to donate artworks for a grand auction, raising money to lift street kids out of poverty. The center supplies the means, media, and guidance for youths to express themselves creatively, as well as guidance on finding employment. Now, eight cities in Morocco boast one of these centers.

On the third day of FLAM, the first session was entitled “An African history of the World, a World History of Africa.” Felwine Sarr, the Senegalese writer, academic and musician, talked about the “further partitioning that invents Africa, effected by archives, libraries, bookshops and museums: the Arab-Islamic, the Colonial, the African American…” More division, then, into samples and specimens, as well as via maps, which, since the nineteenth century, have been drawn by and favor the West. Mamadou Diouf, a historian and professor at Columbia University, spoke of Glissant, Césaire, and Senghor, créolisation and négritude, and the “grammar of emancipation” that must comprise repossession and restitution. The panel called for a re-seeding of objects already in museums, and for more commentaries capable of undermining and challenging the mainstream western discourse to allow these “traces” to announce their abolished histories, so that, for example, a colonial map might depict the slave trade it was based on. Sarr asked:

How can we renew African stories and local communities after colonization, and get back the connectivity we had? The only way to constitute a history outside of the West is through the history of the everyday. Because the history of institutions is a political history. We need to open a space for the contradictory, to subvert the dominant discourse. How can we imagine new paths without the old ideologies, and create space for the peripheries, for the young, for relationships, to revive cultural memory and the history of others?

History is always plural, Diouf reminded us. “As Africans, we can’t not talk about sanitation, or the irresponsible global transnational industries that create infectious diseases, the erosion of biodiversity and deforestation, and the consequences of such loss of diversity. Landscapes are people; our first work is to stand in relation to this confused landscape.”

Valérie Marin La Meslée, a writer and literary journalist for the French magazine Le Point, recalled how Paris during Covid had transformed into a spiritual landscape, and conversation reverted to ordinary greetings so typical in Africa, simple enquiries after people’s mothers, fathers, families.

That afternoon, a conversation between Felwine Sarr and Christiane Taubira formed the festival centerpiece; the threads I’d been following were converging. It was Sarr who brought us back to the overarching moment we were all inhabiting, which I for one hardly dared acknowledge. He spoke of “the rise of ignorance, the hunting of immigrants and unheard-of brutalities.”

“A year ago, we had the same thing in Senegal,” he noted casually. “An attempt at dictatorship, to confiscate democracy and ignore the will of the people. Of course, Senegal is a much smaller country than the United States [he bowed ironically], but I see we are in the valley…”

I gripped the seat in front of me, straining for a glimpse through this longer lens. “I place my confidence in time and history,” Sarr went on. “Life is strong; it resists. When people reject what is happening, when they mobilize, they can overcome. Right now, in many places and homes, a spark is being lit, vigilance is growing. But for a revolution of the imagination to happen, we need time…”

Taubira agreed with Sarr: “We are in a dangerous place now, because the people we’re facing hate laughter and intelligence, they hate poetry.” She, too, invoked the power of the imagination to overcome. (I remembered her comment from the first day: “I love the sensual dimension of reading, and writing. I love films, music, and making love — they’re the only ways I can stay sane in this world run by madmen.”) Towards the end of the conversation, Taubira and the session’s moderator, Rodney Saint-Éloi, fell to reciting Aimé Césaire, like the old friends they undoubtedly were. Césaire had provided a title for the session: The world falls apart. But I am the world.

The last of the last suns

sinks.

here will it set if not in

Me?

As each thing was dying,

I – I grew larger – like the world –

And my awareness greater than the sea!

Last sun.

I burst.

I am the fire, I am the sea.

The world falls apart.

But I am the world.*

The night before, FLAM had shown a film about Frantz Fanon, Cheikh Djemaï’s Frantz Fanon, Une vie, un combat, une oeuvre (2021), in addition to hosting two sessions on Fanon that morning, but on account of my perennially bad back, I had missed them all. After another few hours’ sitting in the riad that day, as the sun passed slowly over our heads, I needed to lie down again. It was only day three, but I knew I was done. At the hotel, to console myself, I sank into rereading Les Pur-Sang (The Thoroughbreds) — had I ever really read it? — astonished at Césaire’s command of language and nature, and his compressed extravagance, whose dynamism and precision were perfectly calibrated to this apocalyptic moment. Here was relief at last, the relief of cosmic revolt.

It seemed to me then, lying on my bed, that this line of extraordinary Martinicans from the early twentieth century — Senghor, Césaire, Fanon (one of the earliest, most radical thinkers for those in the African diaspora), and Glissant — all stood at the brow of the hill now like the cavalry, showing us what resistance could be. The slave trade in Martinique, based on sugar, had only ended in 1848, Tropiques was published 1941-45, and the climate crisis, of course, was already urgent by the 1960s.

Soon I was online, where I excitedly stumbled upon a paper about Les Pur-Sang by scholar Jane Hiddleston,[i] who sets out the “clear continuum” between the subjugation of land and sapping of resources to the demands of imperial capitalism in the Caribbean plantation system via enslavement. Reading Hiddleston, whose paper is rich with literary allusions and connections, reminded me that the French verb résister means not just ‘to resist’ and ‘stand against,’ but also ‘to keep going.’ She quotes René Ménil, who, like the other founder-contributors to Tropiques in wartime Martinique, was writing in coded opposition to the Vichy government — from the point of view of life, everything is in everything, everything is related — before jumping to Diderot, who makes those same exact points, noting, in Rêve d’Alembert: “Everything is in perpetual flux.”

So it is the horizontal that matters, I thought happily, not the crushing vertical hierarchies, global dominance, sovereign rule, or any of the other supremacies we labor under or rail against. This “perpetual flux” is a different and a collaborative power, very much like the Maōhi concept of mana: a life force and supernatural energy, which, like a universal pulse, protects and inspires, that runs through earth, plant, animal, or human like electricity, but also through the dead and the ancestral, the elements and climate, individual and collective language and consciousness. Not quite animism, but Yeats’ spiritus mundi or Jung’s “over-soul” come near. Mana too is not an inert but an active power, which can be cultivated, as well as controlled, by the individual, and also has a moral, karmic or spiritual dimension: affected by and affecting actions, attitudes, and relationships, maleficent and/or beneficent.

A comforting thought, surely, given all the hope and terrible fear compressed into this past year. Into the festival, too, during which I don’t remember anyone daring utter the word “Palestine.” I did, however, hear someone offhandedly say, “The West doesn’t do dialogue, it only soliloquizes,” as if it was a quotation or an old saw. Perhaps the so-called peripheries are approaching the center — a center that cannot hold, having long since forfeited any real authority. Voices from the “margins,” echoing everywhere, are calling out the hypocrisy and complicity of the floundering powers-that-were. In Albert Cossery’s Violence and Derision, a novel set in the Middle East, the author argues the futility of locking horns with your oppressor, advocating instead a campaign of undermining by means of mockery and laughter. Mere anarchy would be a fine thing right now, was my thought as sleep came, but organized, derisive, flamboyant resistance would be better.

*Author’s translation.

Notes

Jane Hiddleston, Everything is in Everything: Tropiques, Césaire and Ecological Thought. ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, Volume 32, Issue 1, Spring 2025, Pages 133–153, https://doi.org/10.1093/isle/isad050