Moroccan director Asmae El Moudir’s experimental documentary has something to teach about unreliable memories and the violence of silences.

Brittany Landorf

In the trailer for Kadib Abyad or The Mother of All Lies, a small figurine appears bathed in a reddish-purple haze. An old woman raises a miniature cane as her hooded eyes glare suspiciously. Her looming gaze is juxtaposed by the faint glitter of her rhinestone hijab and pale floral jellaba. As the light flickers and mellows to soft blues, a voice laments from above: “Ahh, they’ve deformed me! Look — they’ve deformed me — ‘awjawnī!” The camera shifts, peering behind the shoulder of an old woman examining the miniature likeness in her hand using a magnifying glass. The old woman continues to cry out: “They’ve deformed me —‘awjawnī, see how they’ve deformed me!”

This scene, which comes early in Moroccan director Asmae El Moudir’s experimental documentary, depicts her grandmother’s reaction to the doll-like representation. While initially humorous, a sign of her grandma’s cantankerous nature which is never pleased, its framing in the trailer highlights the tension motivating her grandma’s rejection of her representation. Her cries of “you’ve deformed me” gesture to central questions concerning the politics of memory and forgetting motivating the film: How do we remember troubled pasts? What stories do photos tell or hide?

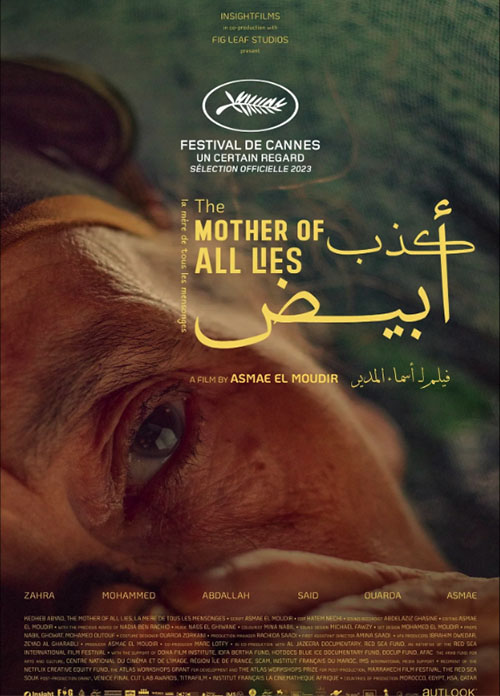

Shot over a period of eight years in Casablanca and Marrakesh, The Mother of All Lies (2023) is El Moudir’s first major film. It has been lauded by international film festivals and was Morocco’s entry for Best International Feature Film at the 2024 Academy Awards this past year. Her innovative documentary style has been praised, and she won the directing prize in Cannes’ Un Certain Regard Section. El Moudir is motivated by the possibilities and limits of photographs as repositories of memory. Her first film, The Postcard (2020), follows the discovery of a postcard of the rural mountain village Zawiya, to explore her mother and her maternal family’s past.

In The Mother of All Lies, Moudir asks who holds the story when its traces have been effaced. In translating the Moroccan Arabic title from “a white lie” (kadib abyad) to “the mother of all lies,” the author plays on the genealogical roots of silences and buried violence structuring both her family’s and Morocco’s pasts. As she has observed in a recent interview for Hammer to Nail: “For me, ‘kadib abyad’ is about how I asked why, in our family, we have no pictures anywhere. Why? I started this film in 2012, and in 2016 I discovered that there had been a big riot in the street where I grew up and I understood that our family’s story was part of a much larger story. And so both the ‘white lie’ and the ‘mother of all lies’ refer to the process of discovering that story.” Yet, as her grandma’s cry resounds, El Moudir is careful to also consider how narrative, film, and photographic representations of these silences may also distort as they uncover.

Throughout the film, El Moudir threads the parallel exploration of her family’s lack of photos alongside the Moroccan state’s brutal repression of the strike against high bread prices on June 20, 1981, known as the “Casablanca bread riots.” A key motif she considers is how burning family photos and burying bodies in unnamed graves can effect multiple, interconnected layers of erasure. To narrate injustices that bear no records, El Moudir turned to the technique of sandplay therapy, a method of semi-scripted play therapy using dolls, puppets, or other toys. Drawing on her father’s expertise as a builder, she worked with him to recreate her childhood neighborhood (darb) in clay miniature. They spent years, attentive to the smallest tile and even wiring actual miniature light fixtures. The replica of her neighborhood provides the stage for her family and neighbors’ recuperation of what were known as the “Years of Lead” during the repressive regime of the late King Hassan II, 1956-1999.

The film is semi-scripted; its narration split between El Moudir’s present self and El Moudir as she imagines her childhood self. Within this narration, she interweaves scenes acted out by her two neighbors, Said and Abdallah, and her parents. Her grandmother, the film’s designated antagonist, roams the set, inserting herself at will. Some of the most powerful moments in the film emerge in Said’s and Abdallah’s recreation of the events surrounding the bread riots on June 20, 1981 and her grandmother’s reaction to these tellings. Abdallah, in particular, responds strongly to the grandmother, calling her “The Makhzan” and “makhzani.” In Morocco, the makhzan refers specifically to the Moroccan state, deriving from the state’s historical role as a “storehouse.” Colloquially, it also can connote the meanings of “dictator” and “authoritarian,” which is how El Moudir translates the term in English. In two tense moments, Abdallah breaks down and wishes to leave as he equates the grandma and her insistence on erasing the events of those days — because “the walls have ears” — with the same repressive power which caused him to be arbitrarily arrested, taken from his house, and thrown into a small jail cell full of 36 children and men who suffocated to death.

As the film unfolds, the parallel between the grandmother as the Moroccan state, embodied by King Hassan II, shifts. While El Moudir’s narration and the semi-scripted scenes and shots employ this comparison, the directors also subtly unravel it as her grandmother navigates her own relationship to memory and photos. At a certain point in the film, after the grandmother accuses her daughter-in-law of “stealing” and “lying” about a photo of El Moudir as a child, she breaks down and weeps. Is it, El Moudir wonders, the first time she has seen her grandma cry? Her grandma’s insistent burning of all photos and refusal to have her own taken are traced to a violence of her own. El Moudir’s recursive genealogy thus reveals not only her own lack of photos but her grandma’s, which is rooted in a too-early marriage and domestic violence.

In a film marked by the violence of silences, it is notable that the film itself perpetuates clear omissions. El Moudir’s attention to her grandmother’s hypocrisy — revering the photo of King Hassan II when she destroys all other photographic material — obscures the director’s own contradictions. Although the photos of Hassan II repeat everywhere — in the grandma’s real home, the dollhouse recreation of her home, on the cover of the 12-year old martyr, Fatima’s, fifth-grade project on the Green March, there are no photos nor mentions of the current King Muhammad VI. Further, no connection is made between the Casablanca bread riots and the 2016-2017 Rif protests.

A telling moment occurs after the celebratory scene for her grandmother’s birthday. As El Moudir, her parents, and neighbors wave sparklers, clapping and dancing around her grandma who seems to be experiencing real joy, the old woman ululates, tilts back her head, and calls out: “Long live the King! Aash al-maalik!” Her grandma’s cry dampens the buoyant mood; she is, as El Moudir observes, “a killjoy.” El Moudir frames the collapse of the mood and the return of her grandma’s censorship as her continued love for the repressive ruler, King Hassan II. Yet, it is unclear why her grandma would wish a long life on a king who died over twenty years earlier for it is unlikely that she will live nearly as long. In occluding her grandma’s reference and reverence for King Hassan II’s son, King Muhammad VI, El Moudir seems to imply that the injustices and human rights violations perpetuated by the Moroccan state, the makhzan, are a thing of the past.

The silences toward the current regime may be explained by El Moudir’s own insistence in the film: “I am a director (mukhrija)…Not a journalist (ṣihāfa).” Whereas in her grandmother’s world, to be a journalist is to be reputable and explains her granddaughter’s desire to dig up past injustices, in Morocco today, to be a journalist is to be vulnerable, at the whim of the very regime, that makhzan, that El Moudir intimates is a memory. Instead, as an artist and a director, El Moudir has benefited from the Moroccan state. Her film was sponsored by a state-funded Atlas Workshop, won the Marrakesh International Film Festival’s best documentary film prize, and has emerged as an emblem of Morocco’s dynamic film industry. In her interviews and public address, the director has praised the king directly, thanking King Muhammad VI for his support.

The director’s relationship to her grandmother, like her relationship to the Moroccan state, is complex. At once denying the crimes of past silences and attempting to wrestle with them, El Moudir also traces the personal trauma of her grandmother and attempts her own healing through film. While the past Moroccan king, Hassan II, is critiqued throughout the film, incidents of current state violence go unmentioned. This omission reveals, as El Moudir reminds the viewer through her slide from present-day to child narrator, that memory and how we narrate the past is slippery. Memory consists of multiple narrative threads, contradictory and entangled, and truth may be more in the telling than in what is told.