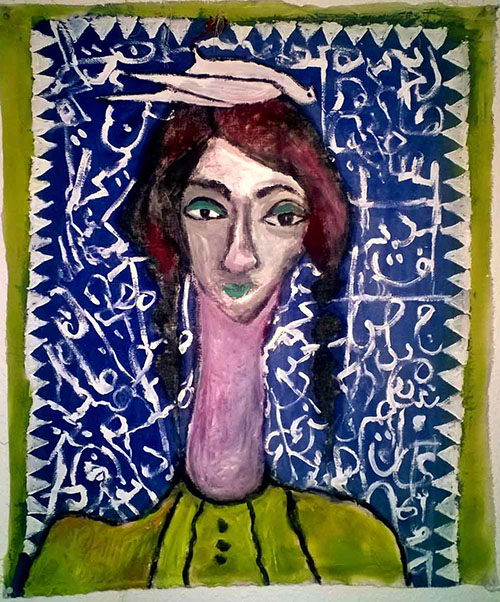

Can a man who loves a woman prove his mettle by taking proper care of a cactus that stings him with its spines?

“I’ve killed two already. Don’t let this be our third,” she told him. Her desolation, he noted, lent her eyes even greater beauty. She added: “I want you to take good care of this one. Do it for me.”

“For you, anything,” he answered.

He had wanted to say something more profound, but staring at her lips arrested the words escaping from his own.

He had had every intention of emailing her, despite his belief in the inadequacy and triviality of the medium. But she occupied a time and space in which he longed to belong, with her. If he were being honest, he’d say that he had never liked being a writer; that, in fact, he felt like an impostor each time he wrote anything. Generally speaking, he’d always thought of himself as insignificant and foolish.

He started to clear the table. Everything in his room reminded him of her: his clothes, his books, his notes, his toothbrush, his coffee cup, his cologne, his leather jacket and that little cactus occupying pride of place in the middle of the well-worn granite table. He wanted to make space for his computer so that he might sit down and try, once more, to write to her. He unconsciously rubbed his thumb against his fingers, recalling the previous day’s pain when he’d attempted the same. He had been struggling to find the words to write to her when, in frustration, he had gotten up to clear the potted plant off the table. When it slipped from his fingers, he reflexively grabbed the prickly thing, and its spines, each no longer than a grain of rice, sank into his flesh.

“I should lock you up now and throw away the key,” she said. She’d been sitting on his thigh, her gaze playing havoc with his heartstrings.

“I’ll find a way to escape,” he’d replied, with his usual foolishness. He loved to provoke her just so he could observe with fascination the unraveling of her reaction.

“I would do it. I would lock you up right here. I would tell my family that I kidnapped you, and that if anyone wanted you free they would first have to marry us,” she said.

“But how would I eat? How would I smoke? How would I drink coffee? On what would I survive?” he asked.

“You would want for nothing as long as I give you this,” she said, reaching for his hand and placing it between her thighs.

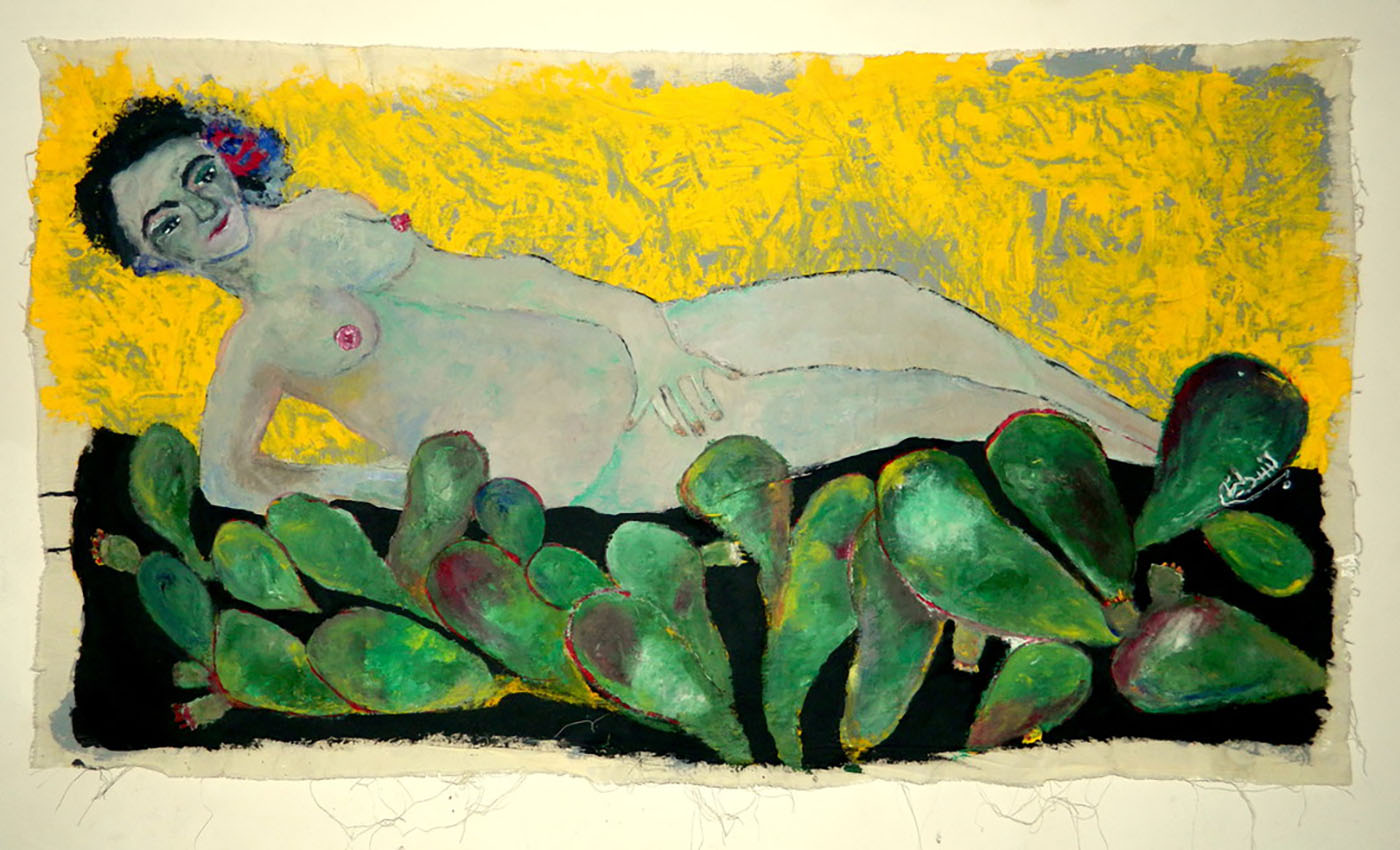

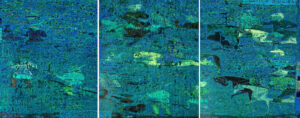

Again he stared at the cactus, and then at the window. Appear. Please appear, he entreated what lay beyond the closed shutters. He made to open them until he remembered he’d promised himself to keep them bolted at all times, even though it meant denying himself a repeat of the scene that had arrested him the first day he’d arrived in the Old City. She’d materialized like an apparition, silhouetted against her kitchen window which looked on to his room. Since then, he’d taken to guessing what she was cooking as fragrant scents seeped through the perforations of his window’s wooden shutters and wafted towards him. He imagined the heat rising in her kitchen to coax out the sweat beads glistening on her forehead. He envisioned the moist droplets running down her face trapping, in their descent, the aromas of cooked fish, tomatoes, pigweed, and onions before sliding down her neck and ultimately pooling in a mass between her breasts. He wished he could ask her how she bore living amidst all the hardships within the alleys of the Old City. He passed his hand over the wooden shutters as if willing them to magically open of their own accord, his eyes pleading for one more sighting. For a brief moment, his gaze shifted to the bathtub placed outside on his balcony, and the combined scents of the yellow flowers bathing inside it alongside pungent mint leaves served to further inflame his lust.

Perhaps her name is Céline, he mused, likening her to his beloved from whom distance, war, and the scrum of life separated him. He surveyed the flowers, trees, bushes, and shrubs in this city, nicknamed the “City of Jasmine” and marvelled at the constant intermingled scent of jasmine and strewn garbage. There’d been a time when he hadn’t had to make such promises to himself, a time when he could have opened the window to anything and anyone, to the sight of an entire garden of blue, yellow, red, purple, and orange flowers in which insects and birds sang along to the rhythm of the sea that adjoined the villa of the French journalist now buried in its grounds.

“You know I have to leave,” he told her while stroking her hair.

“Yes I know,” she replied, desperately wishing it were otherwise.

“This is my chance; I’m going to write down everything. Absolutely everything,” he said.

“Yes. You will write, and I will love it all,” she replied. He knew that if he were to taste her tears he’d fall into a drunken stupor.

“You know I will never give up on us,” he said instead. “It’s only for a few months. We can do it. Everything will be all right,” he added, confident in his sentiments.

“I fear otherwise,” she said. “But I understand your need to travel and to experience the world. You’ve always cherished that idea,” she added, trying to save him the embarrassment of further deceit.

“Yes. I’ve always cherished the idea,” he repeated. He kissed her then, slipping his hand under her skirt.

He snapped back from his reveries and moved away from the shuttered window. He could feel the cactus watching him, and he, in turn, gazed back at it. Gripped by a sudden impulse to leave he grabbed his leather jacket and headed out. Nothing around him resembled his country. Everything was so different: the cold, the air, the smells, the songs, the color of the sky, and people’s clothes, conversations, and shenanigans. Even the city’s gateway to the sea was in huge contrast with Tripoli’s Bab al-Bahr.

It amazed him when his friend Oren, a poet he’d met at the French journalist’s house, detailed the similarities between the two countries, and waxed lyrical about the effervescence of his city and its stories. He failed to see the likeness that would inspire his friend’s poetry each morning on the subject:

He realized that he had reached a street commemorating the man who had begat freedom a home in Tunis. He noted that the cold hadn’t impeded the birds from confiding their secrets to the trees strung along both sides of the street. As he made his way through the corridor of people accompanied by the trilling symphony of African reed warblers, it occurred to him that if Céline, who hated all birds, had been with him at that moment, she would certainly have collapsed from the intensity of birdsong.

Every day since arriving in the City of Jasmine, he would walk for an hour in the villa’s garden. The dusty paths were bursting with foliage, and he couldn’t help noticing their lushness compared to his puny, rigid, and prickly cactus at home. And as he maneuvered his way through the masses of bodies in the street of that beloved man, his Bedouin passions awakened to the women around him, his ardor inflamed by the myriad colors of their hair: blue, yellow, red, purple, and orange, a blooming garden with no danger of a single thorn in sight to puncture his heart.

“I will write to you,” he said, as he made his farewells.

“That’s good,” she replied, her eyes never letting go of his.

“Every day,” he added for good measure. “About everything. It will seem as if we’re barely apart. As you read my words, it’ll be as if my mouth were close enough for your fingers to trace the lips that speak words created just for you.”

“Stay a while,” she pleaded, desperate now that he was finally getting ready to leave. “I want to hang on to your scent, your kisses, and your warm hands a bit longer. Won’t you stay?” Forever was what she wanted to add, but didn’t.

“I’ll stay another hour,” he offered as he encircled her waist.

“I wish I could conceal you from the world, hidden here within my embrace,” she said, squeezing him tightly to her as though coercing his body to fuse with hers.

His hands reached under her shirt to squeeze her breasts as he kissed her neck, ears, and shoulders. He slid his hands downward, slipping them under her skirt where they got busy relieving her of her underwear. “If I am to take the cactus with me like you want me to,” he said, “these will have to be part of the bargain too.”

“You can’t do that,” she said.

“Then it’ll just have to be something else in return for my troubles,” he said pointedly.

When he’d finally left, he’d taken the cactus with him, but not before he’d kissed his love one final time, her eyes shining like two precious pearls he wished he could steal for safekeeping. Eventually, he’d stopped trying to count the number of times the hairline spikes had made a meal of his fingers. When he was ready to leave, he’d packed the plant in his suitcase, but not before another batch of spines had had a go at his flesh. On the plane, all he could think about was the cactus and whether or not it would survive the ten-hour flight delay. As he looked down at the pale, dusty palms, olive trees and cypresses, he had prayed his plant would have enough oxygen to last it the journey. I’ll have to carry it back with me, he’d thought to himself, imagining its size six months down the line and the amused looks he was certain to receive from his fellow passengers as he boarded the plane. He quickly dismissed this last image, knowing he’d never be allowed to bring the plant aboard anyway.

After a full day’s delay, feeling thoroughly spent, he’d arrived in the City of Jasmine in the early hours of the morning, and had finally been able to unpack the cactus from his suitcase before crashing into bed until midday. He wasn’t sure whether the sound of rumbling waves were coming from somewhere close by, or if they were part of his dream in which he dove into the water over and over again to scoop up his love’s pearly eyes, only to come up for air to myriad cactus spines impaling the tender flesh under his fingernails instead.

Three months later, he still hadn’t written a single word. Not about her, for her, or even to her. Each day he woke up to the same morning routine, which started with a breakfast of eggs, coffee, butter, strawberry jam, and a croissant. Most days were spent in the company of Oren, whose habit of bellowing his verses out at the sea had both men falling to the ground in rapturous laughter. Other days he’d spend in solitary walks around the garden, stopping for a rest at his favorite bench beside a nearby pond. It never failed to amuse him how his arrival always startled the frogs, who leapt into the water and upset the serenity of the bright-colored lilies floating gracefully on the surface. Were his love here, he would have reached down and plucked one out of the water in offering. As if privy to his intent to de-home them, the lillies appeared to keep their distance, drifting — it seemed — as far away as they could from where he stood watching them. He named them all Céline.

As he watched the frogs return to the surface, the scene reminded him of a childhood resplendent with stories of frogs, ghosts, and flowers as well as thorns, death, and escape. He supposed that a novel about his childhood might just be the thing he needed to work on. He recalled how Céline had relished his stories, her eyes melting into his as he regaled her, her attraction turning to devotion by the time he came to the end. Buoyed by the memory, he resolved to follow through with this idea, unaware of its folly.

He returned to his room to find the cactus right where he’d left her. As he watered the plant he conceded to himself that its care was turning out to be a burdensome, loveless obligation akin to that of caring for an irksome child. Nevertheless, he carried out his duty, all the while resenting that all the ungrateful plant administered in return was pain.

He picked up a guidebook for writers that he had taken to reading each night before going to sleep, knowing full well that in a few hours he would wake up to another day that would siphon away a little more of his desire to write as he negotiated all the excuses and distractions that kept him from sending her a single word.

The following evening, when the full moon was already high up in the sky and the tide had gone way out, the two friends met at their usual spot at the top of a slight slope overlooking the sea. When each had picked a comfortable rocky surface to sit on, it struck him how the cacti dotted around them bore no resemblance to the one waiting for him at home. It wasn’t long before the two of them were deep in conversation about the war, the sea, God, and all living beings.

“Say, Oren, do you know the names of these plants?”

“Are you asking me from a scientific or aesthetic point of view?” Oren asked glibly, which only reminded him that Oren had trained as a doctor long before turning to poetry.

“For a scientific answer you’ll need an encyclopedia. However, as any poet worth his salt will tell you, one is free to name things as one pleases.” Oren’s answer only served to replace his friend’s previous look of confusion with one of frustration.

“For example?”

“Well, take the cactus over there. Who’s to tell me I can’t call it the orange-hued cactus, when clearly it is orange? Or the blue-colored one right next to it. Why can’t I name it the cactus that lives beside the orange-hued cactus?”

They both went silent after that.

“I believe plants have feelings,” he said, startling them both out of their lull. “That’s why I can’t stand vegetarians who cry to anyone who’ll listen about how animals have feelings, but then dismiss the notion that plants, as living beings, could have feelings, too.”

“Not all vegetarians are like that, my friend,” answered Oren. He sensed, probably for the first time, that Oren had more to say but was being uncharacteristically hesitant. “In the West, animals are subject to terrible conditions,” Oren continued, “cramped pens, growth-promoting hormones, and filthy quarters.” “But who’s to say that plants, too, do not loathe being confined in pots, walled gardens, and cramped beds, harvested according to man’s whims?”

“Science hasn’t yet confirmed whether plants have feelings or not. As for animals, any human with eyes can see the suffering they’re being put through.”

When he’d packed his bags to move to the Old City, he’d decided that the cactus would travel on his lap in the taxi. When he’d gotten into the car, the driver greeted him while throwing several curious glances at the plant.

“Hindis are tasty plants,” said the driver in a bid to engage with him while misidentifying the cactus as an Indian Costus.

“True, but this is a different type of cactus,” he replied, trying to balance the plant on his lap while avoiding contact with its barbs.

The journey was long and difficult. The taxi driver appeared frustrated by his passenger, who seemed reluctant to engage in conversation, prickly or otherwise, and while away the monotonous journey between the two cities. He finally gave up and switched on the radio to keep company with his thoughts.

When the taxi dropped him off at the station closest to the Old City, he discovered that he’d have to walk the remaining distance to the guest house. And so it was that he navigated the last kilometer dragging a heavy suitcase in one hand and carrying a potted plant in the other, making his way through the narrow alleys and markets. By the time he arrived, cranky and sweating, he felt completely spent, his thoughts flashing back to their last time together.

“Keeping this cactus alive proves you’re ready to care for our future child,” Céline said.

“Based on our track record it means our first two will die,” he joked. Then, more soberly, he remarked: “I seriously don’t know where you get these crazy notions — of signs and symbols — from.”

“From here,” she said, tapping her index finger on her forehead.

“Most likely from back here,” he said, slipping a finger to reach back there where he —

Just then, the pot slipped from his grasp, smashing to pieces on the street. The cactus lay sprawled on the dirt, its roots naked, exposed, unearthed from their sanctuary beneath the soil. The dirt seemed to come to life as a light breeze arrived, scattering it every which way, while whatever remained was trampled underfoot by passing pedestrians. As he surveyed the scene, he registered his incompetence, his worthlessness at keeping anything alive, let alone the child that Céline desired. When he glanced back at the cactus he could feel her pleading with him to rescue her. A sudden urge to abandon her exactly where she was overwhelmed him, but it disappeared just as quickly and he sprang into action. He collected as much of the soil as remained and stuffed the roots back into it. Fairly satisfied, he continued on his way to his new abode.

“It’s settled. You are taking her with you,” she demanded.

“Aside from everything, why are you so insistent that I do?”

“She’s my informant. Anything you do, she’ll let me know.”

“But plants can’t speak,” he said. The hypocrisy of his words struck him. Didn’t this contradict his theory about plants as sentient beings?

“She may not be able to speak our language, but she can still prick you whenever she knows you’ve strayed,” she answered. She turned to the plant then, and, gripping the pot in both hands, she leaned in to address it: “Promise me you’ll plant your spikes into him when he thinks of cheating on me.”

“I promise,” he replied playfully putting on a voice he thought the plant might make. They both laughed then, although the incident had left him with an unsettled feeling.

That evening, just before sunset, he took a seat at a café he happened to pass by on his way home. It had been three hours since he’d ordered his first coffee, and both the frequency with which customers entered the café and the number of people in the street were visibly dwindling. Having lost count of the number of coffees he’d consumed and the chain of cigarettes he’d smoked, he looked around to find that except for two other tables — one occupied by a man and two women eating their dinner and another taken by three Libyan youths he could hear conversing about the war — the café was empty. The cat roaming around the place entreating its patrons for food certainly didn’t count; neither did the overweight flower vendor trying to forcefully sell off what remained of her roses to unwilling customers. It wasn’t until he shifted in place that he noticed a woman sitting alone at a table eating an ice cream, whom he’d missed seeing earlier. A powerful longing to get up, converse with her, and to watch her as she ate, washed over him. The emotion dislodged a memory of a long-ago conversation with Céline.

“I dreamed that I was alone when I gave birth to a baby girl,” she said. “I suppose you had traveled, as you always do. She felt like something alien, foreign to me, so that I found it very hard to bond with her, even to look at her. I couldn’t even tell you the color of her eyes, her hair, her skin. I felt neither tenderness nor love towards her. Breastfeeding her felt like a duty rather than an act of motherly devotion.”

“Why?” he asked.

“I don’t understand it myself,” she answered. “Maybe … if only … I’d allowed myself to look into her eyes, I’d have found some answer.”

He spent the rest of the evening alone at his table, imbibing what energy he could from the constantly dwindling flow of passersby. He scrutinized faces, lingering longer on the women. The absence of birdsong aroused an intense desire for the voice of that other woman, who he surmised to be in her thirties, the beauty he stole glimpses of in the window across the alley, the wife of an absent husband, and the mother of the little girl she sang to.

His lucid thoughts were cut short by the shouts of the flower vendor, who was now making him the target of her aggressive designs. Go on! she shouted, pushing a rose towards him. Just take it. He thanked her and declined. He thought of his cactus, and the promise he’d made to covet no other but her. But the woman was relentless, and tried several times to place the flower behind his ear, telling him how handsome it made him look. Dammit it, woman, I said no! he said, his rebuke more aggressive than it should have been. You’re unworthy! the woman spat before gathering her flowers and moving away from the table.

The encounter put him on edge and rattled his nerves. Drained and exhausted, he was barely able to carry himself home, where he was greeted with a familiar melody as soon as he’d stepped into the room and closed the door behind him. Despite not opening his own shutters, he knew that her kitchen window was open, as the verses of her song drifted towards him loud and clear: “The resentful begrudge me my love … they asked me, what it is that I saw in her? To refute my detractors I told them … Take my eyes and look through them…”

He moved towards the table and took a seat opposite the cactus, which appeared to him to be as transfixed by the melodious voice as much as he was. They sat and listened to the woman singing her heart out as she washed the dishes. It seemed that they would spend all night this way, until the calling of Mama, Mama interrupted the woman’s flow. What is it? she asked her little girl. I’m hungry, came the reply. Alright, I’ll fix you something to eat, she replied.

He could detect a palpable change in her tone, one that had gone from seductive melody to another laced with frustration and resignation. He felt a twinge in his chest, so he got up from his chair and moved to the window, hoping to catch a glimpse of her face through the openings of the wooden louvered shutters. A while later, the clatter of pots and pans could be heard as she resumed her place at her kitchen window. He detected the faintest sound of a tune that he couldn’t make out this time. From this viewpoint, he watched her like a hawk as her silhouette moved about the kitchen, amazed how much it resembled that of the one he loved.

Overcome with exhaustion, he finally retired to his bedroom, all notions of writing long gone from his mind. As he set eyes on his cactus for the last time that day, he could feel her thistles piercing holes in his heart, and as he fought the urge to close his eyes and succumb to sleep, he was reminded of a conversation he’d once had with Oren not too long before.

“All women will come to resemble the one you love, but only if you truly love her,” Oren had said.

“But no two women are ever the same,” he’d replied.

“Try it. Imagine a woman. What does she look like?”

“Exactly like the woman I love. But this proves nothing. There are more than a thousand species of cacti, and any similarities they share does not mean that they are one and the same.”

Before he finally drifted off to sleep that night, he resolved that the first thing he was going to do the following morning was to relegate the cactus to the dumpster.

Pingback: On an Award-Winning Novel & the Unstable Literary Scene in Libya – ARABLIT & ARABLIT QUARTERLY