An exclusive excerpt from Gaja Pellegrini-Bettoli’s Generazioni senza padri: Crescere in Guerra in Medio Oriente…Fatherless Generation: Growing up in War in the Middle East, trans. from the Italian by Sarah Mills.

Aboudy’s Roses, or Beirut and the condition of Syrian refugees in Lebanon

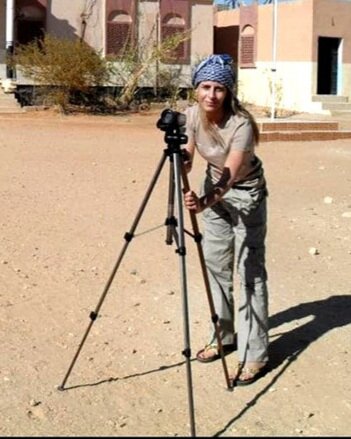

Gaja Pellegini-Bettoli

Aboudy watched the sailboat and smiled. Who could have guessed what he was thinking at that moment? For me, spending time at sea was a way to have fun, but would he feel the same? According to the International Organization for Migration, in 2016 alone, 5,079 people had died or disappeared trying to cross the Mediterranean, fleeing conflict and poverty. Aboudy was eight years old when he arrived in Beirut from Aleppo, in Syria. I had met him one night while at a café in Beirut.

“A rose, madame, a rose for you,” he had said to me, smiling.

“I’m sorry, I can’t—” I had begun to say when Jad showed up.

My Lebanese friend had gone to order a drink at the counter. When Aboudy saw Jad, he threw his arms around him. It wasn’t an ordinary hug; it reminded me more of the way I hugged my older brother.

“I present to you Aboudy!” Jad said.

They exchanged a few words in Arabic, and I found myself with a dozen roses in hand. Jad was a happy-go-lucky sort, too much of a player to date seriously, but educated and sharp-witted all the same. It turned out that the roses were not really intended for me. Jad had gotten them to help Aboudy, and this piqued my curiosity because it seemed out of character; it showed a different side to him, one that was usually buried.

“How do you know him?” I asked Jad.

“He had some problems with his residency permit here in Lebanon, and I intervened as his lawyer,” he explained. “I’ve known him since he was eight.”

He scrolled through his phone. Among photos of parties and women, there was one of Aboudy. What a smile the boy had. There was so much sweetness to it.

The issue regarding Syrian refugees in Lebanon is a delicate one, both for the very high number of refugees — between one and two million, the highest pro capita rate among all neighboring countries — and for political reasons. The latter is not often discussed in the West, but it is crucial to take into consideration in order to better understand the Lebanese outlook on refugees. It is no secret that Lebanon was under Syrian control for 15 years, from 1990 until 2005. Notwithstanding this, it is rare to come across an article about the refugee crisis that acknowledges the effects that this occupation has had on the population.

One journalist who wrote a moving article on an informal tented settlement in Orient le Jour, the French-language daily newspaper in Lebanon, helped me to grasp the situation better.

“You know, I see these kids, in the mud, in the cold, and it hurts to see so much suffering. But at the same time, hearing their voices and their Syrian accent profoundly disturbs me. It reminds me of so many horrible moments that I would rather forget.”

She would have never written such a thing; she only explained it to me in person. Even the use of the term “informal tented settlement” was a vain attempt to clutch at straws.

The Lebanese Civil War (1975-90) had both internal and external causes, many of which have still not been resolved to this day. One of the triggers that sparked war was the divergence between the Christian population in the country — wary of losing its demographic prevalence following the arrival of Palestinian refugees — and the Muslim population. The interests of neighboring countries, such as Syria and Israel, would only prolong and complicate the conflict, the former pursuing ambitions of absorbing Lebanon into a “Greater Syria” and the latter countering the actions of armed Palestinian groups scattered throughout the Lebanese territory. Regardless of political or religious affiliation, however, what came after the arrival of these Palestinian refugees would be permanently etched onto the memory of generations of Lebanese. And war has a way of distorting perception.

The Lebanese population thus became a sort of Oedipus character by unknowingly killing a part of its own history and wedding itself to sectarian causes. The problem of the presence of Palestinian refugees — “resolved” by confining them to camps — became a thorn in the side of the country, at times impossible to ignore or forget. By law, Palestinians in Lebanon are barred from taking up a number of different jobs, which, according to various analysts, keeps them in a perpetual state of poverty despite their high level of education. As a consequence, Lebanon bears a deep scar that is inextricably linked to the civil war. It is for this reason that the prevailing sentiment is strongly opposed to the creation of new refugee camps for those arriving from Syria; even the term “camp” has become taboo, as though using “informal tented settlements” instead could ward off those fears and echoes from the past.

Aboudy’s story is similar to that of many others, and this was the most saddening aspect, in my opinion: There were thousands of children with similar experiences as his on the streets of Beirut. After spending a certain amount of time with refugees and listening to their stories, one ran the risk of becoming desensitized. I walked a tightrope between trying to maintain a proper emotional distance that would allow me to continue my work and preserving my ability to truly listen. There comes a time for everyone in this line of work in which it becomes intolerable to hear yet another sad story. Each night, kids as young as four years old would pour out into the neighborhood of Mar Mikael, in the center of Beirut, and onto one of the busiest streets come evening. They would sell roses and chewing gum. There were never any adults present with them. They would roam from one café to the next, trying to sell their flowers. Some of them, like Aboudy, had been in Beirut since the beginning of the conflict in Syria and were no longer children but adolescents.

Life in the city was different; in small towns, children were more isolated, though this did not necessarily mean that they were more sheltered from the violence of reality on the streets.

Aboudy had kept his sweet face, but his hands told a different story. They were disproportionately large and full of cuts. With his thin frame and smart haircut, smoothed back with gel, his hands looked like they belonged on a different person. I often crossed paths with him during the day, as he pushed a metal cart transporting goods from one store to another.

“Hey Gaja!” he said to me.

When he called me by my name, I realized that I no longer wanted to hide behind statistics and work. I wanted to do something for Aboudy. Perhaps I also wanted to do it for myself, to feel better. You’ve got it all wrong. You shouldn’t be doing something for him, but with him, I thought to myself. A few weeks later, some friends from Italy would travel by sailboat and stop at the Port of Beirut for ten days. It was a chance to take Aboudy sailing.

The boat — the Mediterranean — was part of a project to promote cultural exchange by travelling through the Mediterranean Sea, passing along the coasts of North Africa, Greece, Italy, Lebanon, Israel, and Cyprus. On board were doctors, students, journalists, writers, biologists, and free divers. One part of the crew, which would continually rotate, was on board during the summer of 2015 and witnessed harrowing scenes of refugees landing on the shores of Greece. I had been on board for a week the previous summer.

It must have seemed a strange proposition for Aboudy, initially. I asked Jad to call him and explain what would be happening. Aboudy would trust Jad. We agreed to meet at 8:00 in the morning on Armenia Street, the main road in the neighborhood of Mar Mikael. From there, we would take a taxi together to the port and board the boat. By 8:15, Aboudy still hadn’t arrived. He wasn’t answering his phone, either. I decided to wait. I was about to leave when I heard my name and turned around to see Aboudy running toward me.

“Sorry for being late! I worked until 5:00 a.m. and I didn’t hear my phone this morning.”

“Don’t worry,” I told him. “The important thing is that you got here in time bec

ause the boat sails away tomorrow. Let’s go, yalla, they’re waiting for us!”

When we got to the marina, it was easy to spot our boat; it was the only sailboat in a swarm of yachts.

“Are we getting on that one?” Aboudy asked, pointing to a three-story yacht.

“No,” I told him. “Ours is the sailboat.”

“Welcome on board!” the captain said.

I wanted Aboudy to feel comfortable with me, and my poor Arabic wasn’t helping. On board were the two children of a well-known Italian journalist who was also visiting. They ran from one end of the boat to the other, curious to explore every corner. Aboudy was sitting next to us as we explained to him where the boat had been and what route it would be taking next.

“Be careful!” he said all of a sudden.

The little girl, four years old, was leaning forward; one more step, and she would have fallen overboard. Of all the adults present, it was Aboudy who noticed first.

He was used to paying attention, on constant alert mode, I thought.

We snapped a few pictures. Aboudy showed me the photos that he had on his phone, of his friends and family, of Jad. The phone must have suffered a few blows because the pictures had a psychedelic quality to them. He was proud of the new haircut he’d gotten a few days ago, and he showed me his “before” and “after.” He had been in Beirut for five years, and he had never gone to school since he lived in Lebanon. He had arrived from Aleppo with his parents and five siblings. He spoke a little English, and we were able to communicate intermittently this way.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to take him far from the port, as the captain worried about problems related to transporting a minor, especially if that minor was a refugee. It was now late morning, and the boat was readying to sail off. After gifting Aboudy a shirt as an honorary crew member, it was time to return to the pier.

“What do you say to a second breakfast before going back?” I asked him.

Near the pier was Zaytouna Bay. As we sat by the marina and sipped on our coffee, Aboudy showed me other photos and told me that he hoped to go to the beach the following day, if the weather permitted it. He told me the names of his friends, and we laughed together over my bumbling Arabic.

He was polite. He didn’t behave like an ordinary boy, but rather like one who was forced to grow up in a hurry.

In the taxi, on the way back, I saw that he was tired, and I had misgivings about the excursion I had planned for him. I had merely made him get up early after working all night, I thought to myself, and for a day on a sailboat that didn’t even leave the port. It was he who had given me a gift. As we alighted from the taxi, he approached me in that awkward, timid way typical of a teenager, and gave me a kiss on the cheek. Then he ran off.

A few months later, I was working as a communications consultant for an Italian NGO in Lebanon that handles education for Syrian refugees, when at last I thought I had something worthy to give to Aboudy: a chance to go to school. The conversation would be too complicated for me to handle on my own, so I called Aboudy with the help of my Arabic professor, who was also Syrian, though from Damascus.

“Would you like to go back to school, Aboudy? There are centers that offer recovery programs, and you could sign up if you wanted.”

Things had changed for Aboudy in the last few months, however.

“Thank you, but I can’t,” he replied. “My father is in prison now. They stopped him and found that he didn’t have permission to stay in Lebanon. I’m working to put together a case for him so he’ll be released. I work all day at a barber shop, and at night, I sell roses.”

Bas kilshi tamam alhamdulillah. Those were the few words that I was able to understand on speakerphone. All is well, thank God. His words did not demonstrate resignation, but rather strength, and this expression that once used to make me so angry now took on another meaning as I heard Aboudy say it. Aboudy was already grown up; the war had robbed him and eight and a half million other Syrian refugees (according to figures from UNICEF) of their childhood.

The situation in Beirut was serious: Luxury sat side-by-side with degradation and poverty. It was normal to see a Ferrari drive by trash bins, where refugee children often fished among the refuse, their thin legs sticking out from the open tops. Each Saturday, on the corner of the street where I lived, a father and his two children would stop to search the long line of trash bins. They were punctual; they would be there half an hour before trash pickup came around. The first time I saw them, I felt embarrassed. I tried to avoid their eyes as I passed by them on my way home. I took the long way sometimes, just to avoid running into them.

One day, I was carrying some packages, and it was very hot; I didn’t want to take the long way. The smell emanating from the trash bins was rancid, and the scorching heat was not helping. The older boy was directing his younger brother, who wasn’t even visible, buried as he was in the bin as he rummaged through the trash.

“Marhaba,” I said to the two kids. Their father answered for them, greeting me in return. “Badkon buza?“

Do you want ice cream? It was the only thing that came to mind at the time. I returned with two ice creams and some water. They introduced themselves.

“Ana Omar wa huwe Abdallah, inti?“

Their names were Omar and Abdallah; they asked me mine. I stayed with them the time it took for them to finish their ice creams. It would become a regular thing for us on Saturday mornings.

Then, one day, I didn’t see them anymore.

Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish once wrote a poem that captivated me for its universal simplicity.

Think of Others

As you prepare your breakfast, think of others

(do not forget the pigeon’s food).

As you conduct your wars, think of others

(do not forget those who seek peace).

As you pay your water bill, think of others

(those who are nursed by clouds).

As you return home, to your home, think of others

(do not forget the people of the camps).

As you sleep and count the stars, think of others

(those who have nowhere to sleep).

As you liberate yourself in metaphor, think of others

(those who have lost the right to speak).

As you think of others far away, think of yourself

(say: “If only I were a candle in the dark”).

Misunderstandings are inevitable. We foreign journalists in Beirut and the Middle East were there to try to understand and relay what was happening in the region. Often, we made mistakes; ego, vanity, negligence in verifying reports and sources were all problems we ran into. Everyone wanted to land that one interview that would make them famous. All of us, to some extent, had fallen into these traps. I learned that it was more important to pay attention to the little things, the everyday reality. It was in front of a trash bin that I understood what questions I needed to ask in an interview with a minister.

Beirut: Was it really the Paris of the Middle East? Perhaps, but only for a few people. The contrast between misery and happiness was a harsh wake-up call. The economic situation in Lebanon had considerably deteriorated for its middle class. The arrival of refugees from Syria only aggravated a situation that was already precarious with regard to infrastructure, but economists did not point to this as the root of the country’s difficulties. Instead, the Lebanese pointed a finger at the rampant corruption and at a political system that was incapable of effectively managing the problems plaguing society.

It was a Lebanese who told me, with an irony typical of the country: “As Mark Twain wrote, politicians are like diapers; they need to be changed just as often and for the same reasons.”

________

[1] The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates the number of

Syrian refugees in Lebanon to be 986,942 (as of April 30, 2018). It is important to take into account the different factors behind this estimate. For example, since 2015, the Lebanese government has prevented the UN from registering other refugees. These figures, therefore, ought to be interpreted as indicative of a trend, but are not meant to be taken as precise numbers.