Heart-wrenching and infuriating, the Sawalha family story provides an intimate and personal look at the complexities, contradictions, and dynamics of modern-day political resistance in Palestine, a world that mainstream perspectives have purposefully obfuscated.

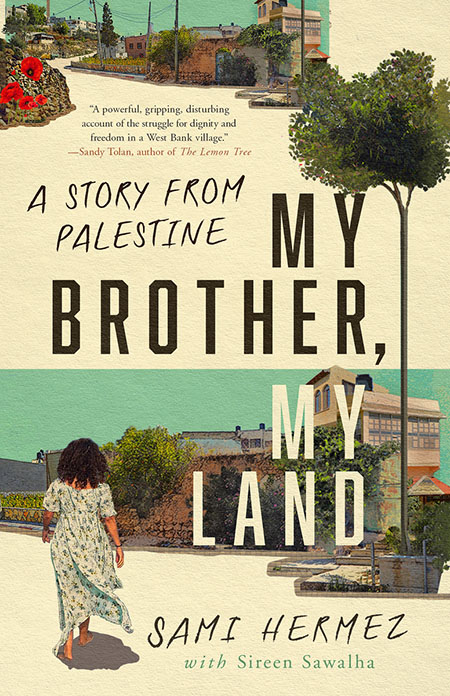

My Brother My Land, a story from Palestine, by Sami Hermez with Sireen Sawalha

Stanford U Press, 2024

ISBN: 9781503628397

Saleem Haddad

There is a moment early on in My Brother, My Land — Sireen Sawalha’s family memoir as told to Sami Hermez — that lingers in my mind. It is 1967, and in the wake of Israel’s victory over the Arab armies, Sireen’s mother, Mayda, makes the decision to travel back from Amman with her children, walking in the opposite direction of thousands of people to return to her family home in the village of Kufr Ra’i in the West Bank.

All lives are shaped by the decisions of one’s forefathers. For Palestinians, these decisions often have stark consequences. My grandparents’ decision to flee Haifa in 1948 for the safety of Beirut inevitably changed my trajectory, providing me with a life free from occupation in exchange for a fate of diasporic rootlessness. Similarly, Mayda’s reverse decision, to return to occupied Palestine rather than join the diaspora, would irrevocably alter the trajectory of the Sawalha family’s lives.

My Brother, My Land, a collaboration between Sireen Sawalha and anthropologist Sami Hermez, tells the story of the Sawalha family’s life from the Nakba of 1948 to the present day. One consequence of Mayda’s decision to return in 1967 is hinted at in the beginning of the narrative: the memoir begins with a flash forward, of Sireen and her mother visiting Sireen’s younger brother Iyad in prison.

The narrative alternates between Sireen’s first-person recollections and Hermez’s third-person exposition, a tool that Hermez says allowed him “to write speculatively about instances where neither of us was present and thus did not know exactly how things unfolded.” This speculation, Hermez is careful to point out, “was informed by research and carried out with an eye toward accuracy and truth.” What emerges from this collaborative structure is a commitment to both truth and memory, two pillars of Palestinian resistance, and a careful balancing act for a people who must write their stories against powerful shadows of obfuscation, lies, and erasure — both physical and metaphysical.

After the opening chapter with Sireen and her mother visiting Iyad in prison, the story returns to the relatively tranquil lives of the family in the run-up to the first intifada. The reasons for Iyad’s incarceration are not immediately explained, and it is this uncertainty that primarily propels the narrative forward through these largely uneventful early years. Still, there is political value in recording ordinary memories of ploughing the land, stealing olives to sell for pocket money, and the humdrum routines of picking wild za’atar. Under the shadow of ethnic cleansing, these simple and unremarkable memories serve as a marker and a record of Palestinian life and connection to the land.

Though the early section of the memoir sometimes veers into auto-ethnography, about twenty per cent of the way through the book, something curious begins to happen. The narrative slowly hones its focus onto a single member of the family: Iyad, Sireen’s younger brother. As Iyad emerges as the primary protagonist, the narrative shifts from slow and meandering childhood memories to something more closely resembling a political thriller: an intimate, gripping, enraging and heart-breaking study of the complexities of armed Palestinian resistance and the ways in which the Israeli occupation tears apart a family and a wider community.

This shift begins around the first intifada. Here, as in various other points in the memoir, the strength of the dual narrative shines. Hermez’s “macro” narration provides a wider context for the political intifada, while Sireen’s first-person recollections offer insight into its impact on the family. In this way, the personal and the political are seamlessly interwoven, illustrating how the wider political trajectory impacts the lives of a single family and community.

As for many young Palestinians at the time, the first intifada marked the beginning of Iyad’s political awakening. Iyad was thirteen when the intifada broke out in 1987, and his teenage years were stymied by military checkpoints, barriers to movement, and regular harassment and intimidation by occupation forces. Iyad becomes involved with the Fahd al-Aswad (Black Panther organization), which was primarily concerned with the controversial practice of the identification and often violent retribution of suspected collaborators. Hermez notes that in the years of the first intifada, around 822 people were killed for being suspected collaborators with the Israelis, and Iyad’s involvement in capturing suspects is presented by both Hermez and Sawalha with admirable ambivalence: a gruesome murder of one traitor — who is subsequently revealed to be innocent — is recounted without attempts to steer the moral and emotional compass of the reader.

Following a surprise military raid, Iyad is captured by occupation forces. Hermez takes the reader behind the prison walls, where the true depth of the brutality of the occupation reveals itself in harrowing passages detailing Iyad’s torture and confinement. While in prison, Iyad experiences a profound political evolution, one that mirrors the evolution of thousands of other Palestinian resistance activists at the turn of the century, abandoning Fatah’s ideas following the tragedy of the Oslo Accords, and turning towards more Islamist-oriented forms of resistance. Iyad discovers the political ideas of Fathi Al-Shiqaqi, the founder of the Palestinian Islamic Jihad. This evolves Iyad’s understanding of the Palestinian struggle as an anti-colonial one: “Palestinians were not locked in a battle between the West and Islam. Theirs was an anti-colonial struggle, where the Zionist movement served as a direct extension of Western colonialism.”

From her new life in the U.S., Sireen helplessly tries to secure her brother’s release. In poignant passages, Hermez captures the exilic pain of the diaspora, which mirror the experiences of those of us currently bearing witness from afar to the latest horror unfolding in Gaza:

“[Iyad’s] incarceration often weighed on [Sireen] as she walked down the streets of New York, smiled among friends, or stared out at the city lights at night. Guilt often consumed her happier moments. Distance was no longer measured in metric units but in the space between incarceration and freedom … The guilt of continuing with her life was insufferable. But she had a child, she had a life in the US, and so she was forced to compartmentalise it in her mind a day or two later as her heart refortified its walls and life trudged on.”

Upon his release, Iyad joins and quickly rises in the ranks of Islamic Jihad, spending much of his post-imprisonment life on the run. This narrative, gripping and increasingly claustrophobic, mirrors the slow-encroaching suffocation of the land as the occupation reaches deeper into the West Bank. The family’s movements become increasingly difficult, their lives slowly throttled, slowly and almost imperceptibly, until — in a passage late in the memoir — Sawalha recounts her attempt to travel from one town to another in a passage that could have been taken straight from an action film.

One of the strengths of My Brother, My Land is that readers are provided the space to reckon with their own stance on controversial and often violent acts of resistance. In the eyes of Israel and indeed much of the Western media, Iyad is considered — unequivocally-— a terrorist. And not just any terrorist, but an Islamic terrorist. But Hermez and Sawalha’s recounting of Iyad’s story provides color and texture to this flattened narrative. Iyad is neither lionized or idolized, and this complex rendering serves as the book’s biggest strength. The narrative becomes an interesting Rorschach test, an unapologetic and judgement-free recounting of the political evolution of a Palestinian resistance fighter. Readers can leave the story with different conclusions as to whether Iyad’s journey is one of political “awakening” or political “radicalization.”

Upon finishing this memoir, I was filled with a terrible, though not hopeless, sadness: sadness at how insidious and divisive an occupation is, how it burrows itself inside the occupied subject, tearing apart families, dividing communities, forcing people to turn on their families, their communities, their own selves. And yet the sadness I felt reading the Sawalha family story was not without hope: hope in the family’s resilience, in humanity’s capacity for resistance and survival, despite all odds.

As the narrative races towards its final, heart-breaking but seemingly inevitable conclusion, I found myself mourning a life that could have been, a life where Iyad spent his time in proximity to family, rather than remaining a shadowy figure that appeared at the family’s front door rarely and without warning, before once again disappearing in the dead of night. And it was not just Iyad’s own estrangement that I mourned, but the estrangement of the Sawalha family from one another: many of the siblings — including Sireen herself — were forced to leave Palestine to pursue lives elsewhere, rendering the family fractured geographically, if not literally. How different would their lives have been had Mayda never decided to go against the tide of displacement and return to their home in Kufr Ra’i? Judging by the history of my own family — similarly scattered around the world like pellets of a shotgun — I can’t help but feel that the choice is a false one. In the end we are condemned to the same fate, and resistance against occupation our only hope for survival.

Heart-wrenching and infuriating, the Sawalha family story provides an intimate and personal look at the complexities, contradictions, and dynamics of modern-day political resistance in Palestine, a world that mainstream perspectives have purposefully obfuscated. Without condemnation or exaltation, a quiet passion simmers between the pages, one that does not threaten Hermez’s earlier commitment to write “with an eye toward accuracy and truth.” Instead, this collaboration sets a model for what writerly solidarity can look like.