When writing about the Kurds, make sure to dismiss the ‘alphabet soup’ of their complex politics, downplay their culture, and project all your own political ideas onto their “tragic,” “abandoned,” and “stateless” homeland. And don’t forget to mention the moustaches, writes our contributor.

Matthew Broomfield

Did you know there’s an ancient Kurdish proverb: “no friends but the mountains”? What better way to title your piece? And never mind that this melancholy, melodramatic, supposedly “ancient” bit of wisdom is of recent and quite possibly Western origin, seldom appears in Kurdish, and was popularized just in time to soften the way for the USA’s first intervention in the region.

Thereafter, make sure to use: “divided,” “doomed,” “tragic,” “abandoned,” “stateless” (never “anti-state”). Or, if you feel differently: “fierce,” “statelet,” “mountain people,” “nomad,” “terrorists,” “Marxists,” “warriors” (never “soldiers”). And if you’re feeling particularly literary, throw in a “moustachioed” or two.

Make sure to emphasize how difficult it was for you, the only true friend-but-the-mountains, to fly into Iraqi Kurdistan’s international airports. Describe the “intent and logic” with which you navigated workaday bureaucracy, your “daring mission” across the Syrian Kurdish border (waiting politely for 20 minutes in a reception room while drinking juice), or simply pose with an AK-47 and write the story about yourself.

It’s a little harder to get away with par-for-the-course Orientalism in Jerusalem or Istanbul these days, but Kurdistan is ideal. It remains “remote,” “hard-to-access,” the “Wild West” but also safely, uniquely “pro-Western.” So feel free to trot out to the “barren deserts,” “inhospitable peaks,” “bustling bazaars,” “over-sweetened tea,” and all the rest of it. By even visiting Kurdistan, you’re doing the Kurds a favor, after all. Who cares if you get a few details wrong? (Perhaps, like the author of this piece, you might even smugly condemn clichés and stereotypes you’ve been guilty of yourself).

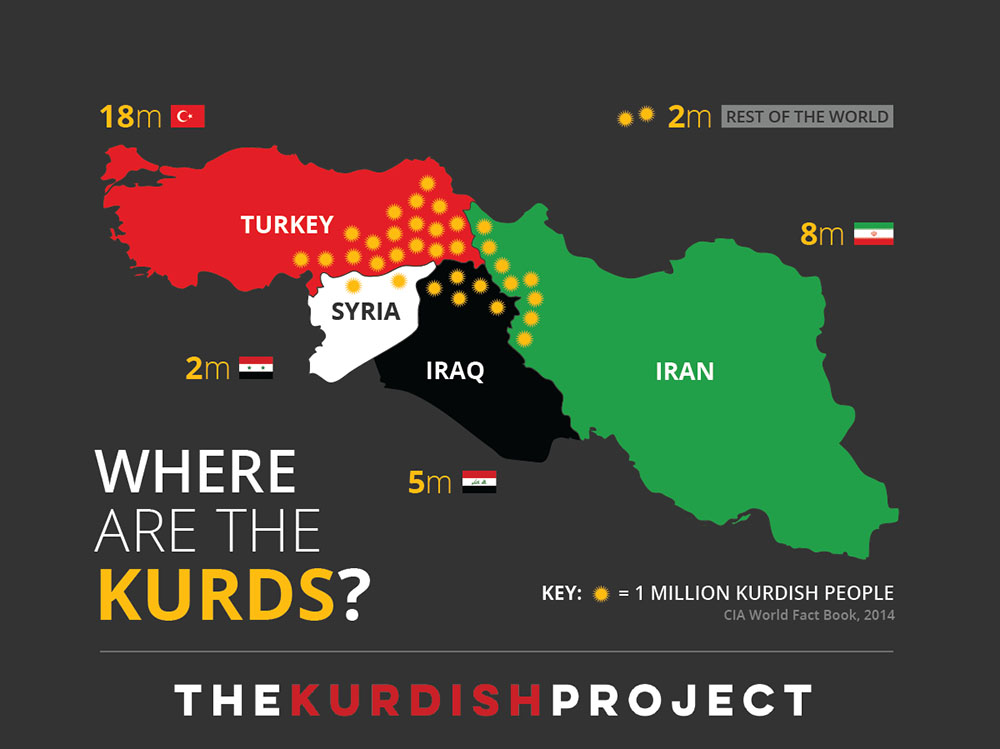

More likely, you won’t travel to the region at all. What’s the point? You can file your story from Istanbul — or Washington. You’ve seen a map, drawn up by a think-tank, which can help readers understand the basics. Just “who are” the Kurds, anyway, and why are they making such a fuss? Good question, even though you’ve already settled on an answer, and even though it normally only comes up when the Kurds are already being ethnically cleansed, by which time it might seem a bit late.

It’s complicated, and you don’t want to bore your readers — make sure to apologize for the “alphabet soup” of Kurdish political organizations. Feel free to mangle the official names and acronyms of these trivial, semi-recognized entities and “quasi-states.” Why can’t they all just get along? Conflicts between Kurds are childish squabbles, fratricidal foolishness. As such, you’ll focus solely on politics — never culture, literature, or history — without actually discussing Kurdish politics at all.

The Kurds are all “pro-Western imperialists,” paid to destabilize the region — though Turkish Kurdish militants have been fighting NATO for forty years, and the CIA was in fact funding Saddam Hussein as he conducted genocide against the Iraqi Kurds. Or else they’re all “separatist Marxists” — though they abandoned the struggle for a socialist Kurdish state decades ago. The Syrian Kurds are “stealing Syrian oil” — to feed other Syrians in Syria, as it happens. Kurdish women are inherently emancipated — despite battling honour killings, tribalism and patriarchy within their own communities. They’re defenders of (white) Christendom against barbaric Muslims — and never mind that the Kurds are primarily Sunni Muslim themselves. They’re precisely your personal, chosen flavor of eco-feminist-anarchist.

Of course, you have no idea what diverse Kurdish political perspectives on Marxism, capitalism, the state, the West, Islam or women’s liberation actually entail. You’re unlikely to speak Kurdish, or read Kurdish political theory. It’s all propaganda, anyway. Propaganda is what Kurds do: the Turks send out press releases.

Feel free to report on anything Turkish officials say about Kurds — but remember the “right of reply” applies only to the victims of state violence, never its executors. If you absolutely have to include a Kurdish perspective, make sure it’s a military commander, never a politician, and certainly not anyone from civil society. Speak only of a “battleground,” the “frontlines,” and “hideouts,” never of diverse cities home to millions of civilians.

At the same time as you refuse to speak to any political or civilian representatives, make it crystal clear the armed representatives are illegitimate, “outlawed,” a “designated terrorist organization” — but never explain who imposed that designation, or that a European court found it was nonsense. Did you know that “the Turkish-Kurdish conflict has left 40,000 dead?” It’s equally mandatory to include that dubious statistic (a Turkish government claim, which hasn’t been updated for over two decades) somewhere in the opening paragraphs — but make sure you use the passive voice, and never state who’s actually to blame for the bulk of those killings.

Clearly, there must be two species of Kurds: the news agencies know the Kurds can only ever be terrorists, but the feature writer and movie-maker are up in the mountains, meeting a different sort. To them, the Kurds are “good guys” in a “bad neighborhood.” In particular, their women are “Amazons,” “badass,” “Angelina Jolie” in fatigues.

You can focus pruriently on their sexual politics, suggesting the fact these women don’t want to marry, drink alcohol or have sex proves they must be in a “cult.” If Kurds sacrifice their lives for freedom, they must have been brainwashed. But don’t take their unique ideology seriously — it’s just a smokescreen, hiding the fact men are still the real commanders. Everyone, even the feminist-military complex, knows women can’t really fight. Instead, if you’re making a movie, add some personal motivation, a lost relative who the Kurdish militant wants to find. That’s the only reason a woman would ever fight at all — unless they were seduced by a “Kurdish lover boy,” of course.

In movies, Kurds serve best as sidekicks, loyal helpmeets to American soldiers, willing to sacrifice themselves to protect “us.” Make sure they never get to explain what they’re fighting for, or why. You might find it convenient to replace Kurdistan with another, made-up “-stan” altogether; you can explain you wanted to “universalize” your message, and so you had no choice but to drop the politics, make your protagonist an international volunteer with Kurdish forces, or quite simply a foreign ISIS militant.

The same goes for documentaries. Try to only ever interview foreign ISIS members about their plight. Let them freely blame “the Kurds” for their mistreatment, rather than speaking to the young Kurdish women who vanquished them and now secure and care for them each day on behalf of global powers which turned their backs as soon as the bombs stopped falling; don’t risk repeating the Kurds’ call for international support to help them solve this global crisis. Too political. And never mention that countless local Kurds and Arabs are living in equally grim conditions just down the road. If you did that, you’d have to admit that you consider everyday life in Kurdistan a punishment in itself — fine for local Kurds, but not for Western ISIS fighters.

If you can, omit your subject’s Kurdishness altogether, representing them as a “Syrian refugee” or “Iranian woman” — even when it’s literally in their name. That way, it will be even easier to represent Kurdistan as a “no man’s land,” a space “without people and owners,” a blank canvas waiting for neocon intervention. Perhaps you can even get Hillary Clinton on board as a producer.

Kurdish survival is contingent on whether the Americans stay or go. After all, the Kurds have always been hapless, subjugated victims. Kurdish politics only started with the American intervention in Iraq in 1991, or else with the American intervention against ISIS in 2014. So there’s no point asking where the Kurds came from, or how their society was organized before Ba’ath socialism and Kemalism. They just lurked in the mountains, robbing caravans.

Omit the fact the Kurds have dialects so distinct they would count for different languages if they only had an army (or a state), or the political and cultural differences between these regions. In particular, you are unlikely to mention Iran’s Kurds at all — the Iranian opposition is uniformly monarchist and liberal feminist. So while you might make use of the popular slogan “Woman Life Freedom,” you’ll gloss over its militant origins.

For while there are “good and bad Kurds,” the Kurds are nonetheless a monolithic bloc. By relying on the convenient shorthand “the Kurds” or “our Kurdish allies,” you can omit the reality of multi-ethnic Kurdish-Arab alliances; and evade the inconvenient truth that the “bad Kurds” who struggle against NATO and capitalism are the same ones who defeated ISIS and saved the Yazidis from genocide. In general, it’s safest to show the “good,” capitalist, nationalist Kurds as the heroes, even in battles they took no part in.

If you do raise Kurdish political vision for the Middle East, make sure to discount it outright. As we all know, for example, the ‘Syrian revolution’ has failed — and never mind that millions of Kurds and their allies are still living outside Syrian regime control, insistently claiming that the revolution is alive and well in Syrian Kurdistan. In fact, the so-called “Kurdish question” is a command to the Kurdish people, instructing them to expect no change. There isn’t supposed to be an answer. It’s a “Gordian knot,” after all, best resolved by think-tankers with close relationships to the Turkish state.

You might avoid these difficult questions altogether, concluding with the gnomic reflection that “one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.” But in that equation — who exactly is the “man” sorting Kurds into categories? And who cares what he thinks, anyway?

Inspired by Binyavanga Wainaina’s How to write about Africa, via Lily Lynch’s How to write about the Balkans.