Diran Mardirian looks back on the life and legacy of Ziad Rahbani, and on the story of the man who first brought him to the jazz sound that would transform Lebanon’s musical landscape.

Diran Mardirian

The breast lay on the coffee table, among piles of note sheets, 8-track reels, crushed cigarette packs and large, overflowing ashtrays.

Ziad and my father — who everyone, including me, called Chico — watched me with grins in their bright eyes.

“Come here, Blondie,” Ziad called to me, and then, when he saw me hesitate: “Shou? Fee shee?”

“No, nothing’s the matter,” I mumbled.

He exchanged amused glances with Chico, then asked me if I wanted to touch it.

“Touch what?” I asked, feigning innocence.

“El bizz.”

Almost half a century later, I still retain the unfortunate reaction of blushing violently when embarrassed.

Loud guffaws, then the order: “Press the nipple.”

I looked at dad, and he nodded towards the breast. Life sized, beautifully formed and perfectly nippled.

I pressed it and jumped as a shrill ring filled the living room.

Roaring laughter as my blush steamed my face so hot I began to sweat.

“Just messing with you, Blondie,” Ziad said, mussing my yellow locks.

“Come, I think you’ll much prefer another room.”

I followed him down the corridor to a door he heaved open. Several keyboards, including an electric piano, guitars, gear I recognized but didn’t know the function of — and a drum set.

Ziad immediately caught my furtive look of longing, the same look with which I’d graced the breast.

“You like the drums, yeah?”

“Yes!”

“I love…” and I couldn’t remember the Arabic word for rhythm, so I said it in English.

“Iqa’” said Ziad.

“Yes!”

“Here, let me lower the stool for you,” which he proceeded to do.

He closed the door behind him with a wink, and the room felt compressed. Then, decompression as Ziad popped open the door again to reassure me that I could bang away to my heart’s content; the room was soundproofed so I wouldn’t be disturbing the men of ZIDA at work.

That was Ziad. Irreverent, with a sense of humor bordering on the wicked, yet also attentive, thoughtful and interested in the little guy. In Lebanon, no one refers to him as Ziad Rahbani. The whole country is on a first-name basis with him. Say Ziad, and everyone knows who you mean.

Ziad the child prodigy; Ziad the playwright; Ziad the composer.

The godfather of Lebanese jazz; the communist; the public/political figure; the man.

Ziad.

And it is in that last capacity that I first met him.

Born in 1956 in the sleepy northern Beirut suburb of Antelias, Ziad’s household was anything but. His mother is Fairuz, Lebanese diva par excellence, graced with that unmistakable voice recognized across the Arab world and beyond. His father was Assi Rahbani, who, together with his brother Mansour made a name for themselves as the dons of Lebanese folkloric musical theatre. The Rahbani brothers and Fairuz became highlights on the magnificently star-studded stage of Lebanon’s Baalbeck Festival, which in its heyday featured such illustrious names as Ella Fitzgerald, Nina Simone and Miles Davis. They met with equally rapturous welcome on their rare forays onto the international concert circuit, bringing their art to the Lebanese diaspora (and then some). Fairuz and the Rahbani brothers became Lebanese icons and the country’s premiere cultural ambassadors to the world.

The eldest of three siblings, Ziad had a penchant for music that showed itself early on. He played the piano and started composing music in his mid-teens. Assi suffered a brain hemorrhage in 1972, and Ziad, only 16, stepped in to fill that gap with his own compositions, which were integrated into the massively popular plays starring Fairuz as early as 1973. That same year saw his own debut as a playwright with the play Sahriyye. Set in a rural coffee shop, it features a simple plot perfect for a piece of musical theatre, as the café owner competes with his daughter’s suitor to see who has the more beautiful voice. That was quickly followed by Nazl El Sourour (Happiness Inn), his first true masterpiece. It was his entrance on the scene as a writer of immortal songs, but, more importantly, as a public figure, a visionary who foresaw the future and warned of it with trademark acerbic wit. In the play, Ziad plays a down on his luck gambler who’s been chucked out by his wife and seeks abode at the titular inn, which is quickly overrun by militia goons who take everyone hostage. One year later, in 1975, the Lebanese civil war broke out, and the entire country was relegated to the same fate as the hostages at the inn.

In 1977, Ziad released an album called Bil Afrah (For Celebration), on the Philips Liban label. Philips was one of the three pressing plants operating at the time in tiny Lebanon, a fact that speaks volumes of Lebanon’s outsize music culture. The superb album is quite rare and much in demand. Ziad had gathered a Who’s Who of Lebanese musicians to play his compositions along with him, and the result was completely old school but playful in its delivery, setting it apart from other similar works.

As superb as his compositions were until this point, there was nevertheless a storm brewing in Ziad’s soul, and he was about to undergo a volte-face that would stun the world.

ZIDA Records was born in 1978 Hamra.

For those who don’t know, Hamra was the main thoroughfare in the western part of civil-war-split Beirut. The stereotype has it that West Beirut was the Muslim part of town, as opposed to the predominantly Christian East Beirut, but Hamra was in fact the real West Beirut: cosmopolitan and multi-confessional, with several adjacent universities and a buzzing commercial and cultural scene cohabitating with the clandestine and militaristic set.

For example: Miles Copeland was CIA head honcho at the US embassy in the seaside neighborhood of Ain el-Mreisse, a stone’s throw away from the world-famous St. George Hotel and Yacht Club, stuff of legend and spook haunt straight out of a Le Carré novel. In the 1960s, his son Stewart was a frequent purveyor of Chico’s, my father’s eponymous record shop, and went on to become the drummer of the legendary band The Police. It was rumored that Chico dated his sister briefly. So yeah, Sex, Spies and Rock ‘n Roll.

Hamra, baby!

Chico Records was established in 1964 at the end of Hamra, and, run by the tastemaker extraordinaire who was my father, it quickly became a musical mecca. The swinging sixties had an address, and of course Ziad would become one of its main visitors. He was a frequent presence there as of about 1976. Wishing to explore a world of music beyond the familiar, Chico was recommended to him as the go-to. And it was at Chico’s where Ziad Rahbani would arrive at his musical destiny.

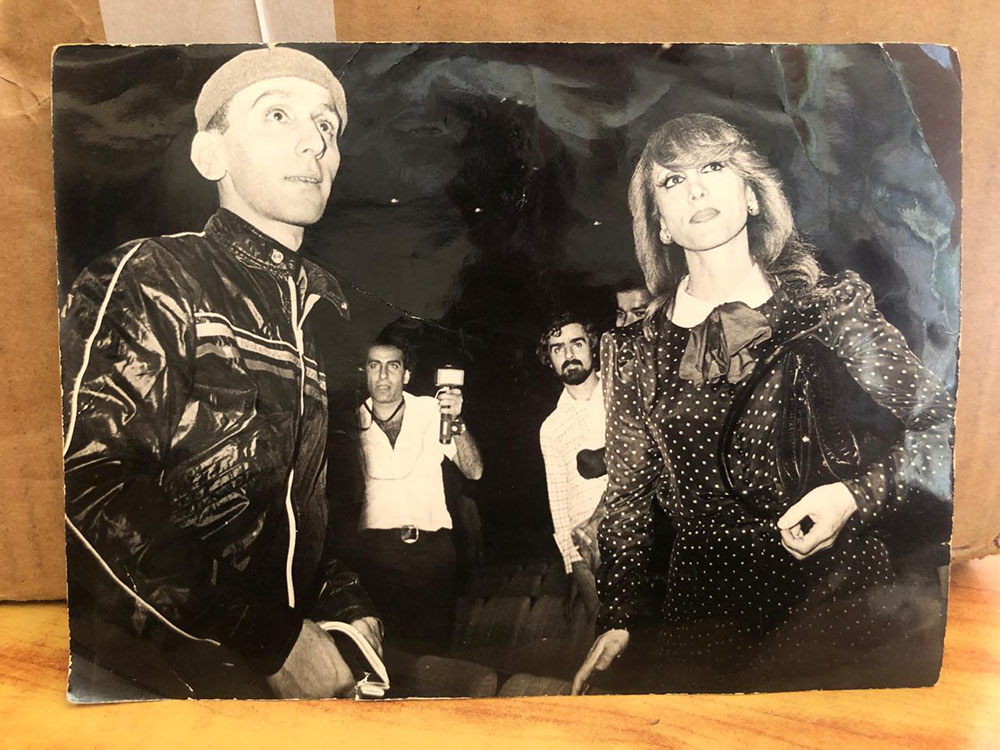

Every day on our way back from school, my older brother Paul and I would nip into the shop. More often than not, there was Ziad, with Chico mounting a reel as a turntable played some crazy jazz tune, and then he’d cut to a cassette with another tasty morsel. It was a two-man flurry of exuberance and ideas. Although I was never privy to the actual conversations that spawned it, Ziad and Chico came to the conclusion that, first, there was potential for a quintessentially Lebanese jazz sound and, second, it needed a solid outfit to carry it. As a result, Chico and Ziad established ZIDA records, with my father as producer and Ziad as musical genius. Upon each new visit, my brother Paul and I saw the project expand, as new musicians and artists like popular leftist singer and songwriter Khaled el Habre, sax supremo Toufic Farroukh, and Issam Hajj Ali, an accomplished guitar player, to name but a few, were added to the roster. Soon, the boys were ready to begin recording.

In early 1979, my father, Ziad and a whole host of musicians traveled to Athens to cut the first music album that would appear on the ZIDA Records label. The war meant the situation in Beirut was too volatile to record there, not to mention the lack of infrastructure for such a massive production. The culmination of hours upon hours of brainstorming and tinkling and writing and rewriting, the resultant album, Abu Ali, is widely considered Ziad’s jazz masterpiece. It was the noisy, exuberant, look-at-me entrance of Lebanese jazz onto the world music scene; the debut of the sound that would cement Ziad’s reputation as a musical visionary.

Arguably the finest oriental funk crossover in existence, Abu Ali sounds as fresh and exciting now as it did almost 50 years ago. Ziad had composed an epic, 13-minute instrumental, drawing inspiration from Black American soul artists who had perfected their game — but he’d gone full orchestral. Think of Grover Washington Jr.’s reworking of “Masterpiece” by The Temptations. These tracks are to this day goldmines of sampling because the music was so tightly produced and brilliant. Abu Ali is way up there, with its fantastic production values still lauded by the experts.

The ZIDA boys, Chico and Ziad, were accompanied by the crème de la crème of Lebanese musicians, such as Setrak Sarkissian, Lebanese Armenian percussion guru, and Joseph Karkour on nay, in addition to the aforementioned Farroukh on sax and Hajj Ali on guitar. A full orchestra of strings and wind instruments was ready to go. Even crooner Joseph Sakr tagged along, flying all the way to Athens to belt out a single line: “Waynak Ya Abu Ali?” (Where are you, Abu Ali?”). To this day, the expressions on first time listeners’ faces when I play them the record is priceless. The project was so grand and intricate, and Ziad such a perfectionist, that the bill ended up being exorbitant. I remember very well the night the phone rang at an unusual hour and my mother’s serious nods as she listened to the speaker on the other end. She then rushed to our tiny storage room while shouting for Paul to help her bring down her suitcase. The next morning, she was off on the first flight to Athens. Later, I’d find out that she’d gone over there with all her savings to help bail out the boys and see the production through. My mother, Abu Ali’s secret midwife. The mega production turned out to be ZIDA Records’ Icarus moment, but that came later.

From then on, Ziad’s sound was distinctively jazz. Lebanese jazz, a creation nearly entirely his own. Simultaneously with Abu Ali, ZIDA Records released a recording of Ziad’s seminal musical play, Bennesbeh Labokra, Shou? (What About Tomorrow?). In my humble opinion Ziad’s most accomplished play, Bennesbeh poignantly combines the skills of all the different Ziads: the social critic, the playwright, the songwriter, the wit, dreamer, prophet, hurt lover, man of the people, and most importantly, the godfather of Lebanese jazz.

And he continued to up the ante. In 1979, he wrote and composed Wahdon, an earthquake of an album, recruiting Fairuz herself into the jazz club. At only 22, Ziad, along with his producer, my father, managed to turn Fairuz, THE Fairuz — for decades revered from the Persian Gulf across to west Africa and beyond as a classical vocalist — into a jazz artist. On Wahdon, Ziad rewrote and rearranged the song “Bosta,” originally sung by Joseph Sakr on the Bennesbeh soundtrack. Against a funky score complete with a whole brass section, Fairuz sang the irreverent little ditty about a bunch of people riding a bus from one Lebanese mountain village to another, and the world got to hear her as they never had before. Wahdon is a masterpiece, combining Bosta with the title track, a melancholy, quintessentially folkloric, song, but again graced with Ziad’s divine jazzy keystrokes and funky arrangements.

Ziad’s power was such that even Fairuz the icon was transformed. Ziad followed Wahdon with the equally excellent Maarifti Feek, also featuring his mother’s vocals. Again, the songs were, and have continued to prove, instant classics: “Li Beirut” (For Beirut), a poignant tribute to a dying city, and “Keefak Inta,” a melancholy dissection of some of the more difficult aspects of Ziad’s relationship to his mother. Almost fifty years later, Ziad’s jazz is the envy of many a vinyl reissue label, and still sells like hotcakes.

Lebanese jazz had made its triumphant debut, but everything else about the country was taking a dramatic downturn. The outbreak of the civil war in 1975 chased Ziad away from Antelias to settle down permanently in West Beirut, in Hamra. It was a natural and necessary move for an avowed Communist. Despite the civil war and the Israeli invasion of South Lebanon in 1978, there was nevertheless still an optimistic outlook during that period of the late 1970s, and a general vibe of bonhomie, as counterintuitive as that sounds. When the civil war began, people, especially committed leftists like Ziad, felt as though they were part of a larger liberationist movement. A movement meant eventually to secure Palestinian — and larger Arab freedom — from the grip of Western imperialism.

But the 1982 Israeli siege, bombardment and invasion of West Beirut brought everything crashing down. The massacres and violence were so awful they famously prompted the conservative Ronald Reagan to chastize the Israelis into stopping their attacks. The PLO were banished from Lebanon, and Lebanon, rid of the Palestinian resistance and hence the civil war’s main raison d’être, slipped into a full blown, ugly, cynical, deadly and now accurately labeled civil war. Hope receded; bonhomie became a thing of the past.

Ziad wrote two plays in the early 80’s: Film Amerki Tawil (An American Motion Picture), and Shee Feshil (Failure). The latter, for the first time, did not feature any songs. This was very telling, for despair had taken over. Hamra, which Ziad adored and had adopted as home, became a broken, shambling relic of its former self, its streets lightless and its corners piled with mounds of garbage. West Beirut was in chaos; the Syrian Army, which had first put its boots on the ground in Lebanon in 1976 had, with help from Lebanon’s corrupt and treacherous politicians, now placed them firmly on our necks. The various militias broke up into ever-smaller factions until the sects were battling within themselves. The civil war would finally end with the signing of the Taef Accord in 1990, but the months leading up to it would prove some of the deadliest and most horrific of the entire war.

Ziad nevertheless persisted, producing Houdou Nisbi in 1985 (since reissued on vinyl record to great acclaim). Its title translates into Relative Calm, referring to the oft reported security situation on the ground in radio news flashes, and as usual it featured some instant classics, including the class-conscious love song “Bala Wala Shi” (Without Anything). Shortly after the end of the war, Ziad produced two plays, Laoula Foshat El Amal (If it Weren’t for the Insistence of Hope) and Bikhsous El Karame Wil Shaab El ‘Anid (Regarding Dignity and the Stubborn People), in quick succession. Also songless, they were chock full of sarcasm — and bitter. So, so bitter. By then he had experienced several shocks to his system. He’d had a disastrous marriage, had witnessed the end of Communism and the fall of the Soviet Union, seen the rise of the new world order, and the beginnings of Lebanon’s rapaciously neoliberal post-war period. While the rest of the country was lost in the fog of post-war euphoria, Ziad once again saw right through to the heart of things, and once again, he was spot-on.

It is in these later, post-war days that Ziad the political/public figure appeared. While his creative production and live performances grew fewer and more far between, Ziad’s voice nevertheless continued to sound — and resound with the silent majority who were also increasingly disillusioned with the era of wanton reconstruction. The rare interviews he gave during that time were quoted endlessly long after they aired, and his penchant for accurate I-told-you-so’s accumulated over the years. The country was in the grips of a neoliberal agenda, and he saw it instantly for what it was. And, always and throughout for Ziad, Palestine was still the issue, to paraphrase the great, late John Pilger, especially that Israel, along with its crazed imperialist backers, remained (and remain) a persistent and continuous threat.

It sounds almost cliché, but Ziad truly fit (having also cultivated) the image of the everyman. He loved himself a manoushe, those delicious, freshly baked, thyme or cheese breakfast delights. He took services (shared taxis) like anyone else. He drank — how he drank — at Barometre, the tiny communist bar tucked away at the end of Makhoul street, where a black-and-white portrait of him graced the wall. He was the truest voice of Youssef Average, of which he himself was the humblest specimen. He remained steadfastly down to earth, but everything else — his city, his home, was changing fast. Beirut was ruthlessly rebuilt, but in what image? And at what cost, both material and human? Ziad’s entire oeuvre was to question what lay beneath the surface of everything, and to prod others to question. And it wasn’t just Lebanon changing into a territory hostile to its common inhabitants. The second US invasion and destruction of Iraq had reverberations across the entire region. Syria burned in a vicious civil war and Lebanon succumbed to a series of collapses so humiliating they left the entire country gasping. All of it took a toll on Ziad. He slowly turned into a recluse, and his voice grew quieter and quieter until its silence was deafening.

“What does he want this early in the day?” I thought to myself as I saw an old friend’s name blink on my mobile.

“Allo?”

“Ziad is dead.”

Like with the JFK assassination, which stunned the US into national mourning, everyone in Lebanon will now forever remember where they were when they first heard the news about Ziad.

I myself had just arrived at work, and was in the middle of making my morning mocha. I put the phone down and looked around at the still-empty store, at the stacks of records and HiFi systems on sale. Chico Records remains a Hamra fixture, though the new store is around the corner from the first, original location. The one where I first met Ziad, and where Ziad first met jazz — and the man who introduced him to it.

I felt many things when I heard the news about Ziad’s passing. A deep sorrow; for him, certainly, but also for my father.

Just like Ziad, my father passed at the age of 69. And just like Ziad, he died as a result of his own defiance. Ziad refused the liver transplant that would have saved his life, the same way my dad refused the chemotherapy that would have mitigated his cancer.

Thirty years prior to his death in 2013, my father had a falling out with Ziad so great it led to a nervous breakdown. He never spoke to Ziad again. Over the years, old comrades, actors and musicians would visit my father at the shop. The subject of Ziad would sometimes pop up, but hard facts on what had actually happened remained elusive to me. My father never spoke of it. Shortly after he passed, I unearthed two letters Ziad had written him, trying to patch things up. They definitely went unanswered. I did eventually find out the root cause of the break, but that part of it isn’t my story to tell. It now belongs to two extraordinary men who are no longer with us.

What’s important is that Chico, though deeply hurt and unable to forgive Ziad, nevertheless refused to harbor any rancor toward his old friend, and never spoke ill of him. As I look back with mature eyes at the whole history of their relationship, I accept that the shattering of their brotherly bond is as much a result of their incredible dynamic as is the musical history they made together. The creative chemistry between these two exceptional men is now stuff of legend, but being extraordinary invariably carries a dark downside, which may render that chemistry explosive, destructive.

I provide here my own assessment of my father’s contribution to creating a jazz legend, but there’s no way for me to know how he assessed it, or how that viewpoint was affected by the tragic aftermath. He was nevertheless badass enough to die on his own terms — just as he’d lived and created. Uncompromising. Just like Ziad. And I am content with the fact that he died at peace with the knowledge that his boys were doing fine, his wife had forgiven him his transgressions, and that he’d paid his dues and owed nothing to anybody. I sincerely hope, from the bottom of my heart, that Ziad passed with the same blessings.

I didn’t go to the impromptu gathering at the Fuad Khoury hospital, right across the street from Ziad’s favorite watering hole, Barometre. But its makeup reveals tomes of who Ziad was. I’ve studied the videos. That crowd? That was Lebanon. The Lebanon all Lebanese wish to have materialize. There stood an entire beautiful spectrum of people, from all sects, of all walks of life, together under a scorching late July sun, bidding our Ziad farewell with great dignity. With no less dignity did his mother Fairuz receive the condolences, as the high and mighty poured in to pay respects to the living legend, and mourn her son, the legend gone-too-soon. Even Hezbollah, in an unusual move, issued a communique that mourned the passing of the Communist, atheist, alcohol-binging playwright jazz artist. While Ziad was generally ultra-supportive of Resistance, he was nevertheless fiercely critical of the Party of God at several junctions. Still, they mourned him. Yeah, Ziad is — was — that amazing.

But the greatness of Ziad Rahbani lies not in the fact that he made everyone love him. It lies precisely in the fact that he made it impossible for anyone to hate him. Even those, like Chico, who were most damaged by his (sometimes brutal) erraticism, difficulty and/or perfectionism, found it difficult to hold a grudge. As true to himself and his beliefs as he always remained, Ziad lived what he preached, and suffered from the fallout.

And he will eternally remain the personification of his country, his Beirut, his Hamra: fatally flawed but brilliant and eclectic in a way impossible to hate. In short, indomitable.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/oldmarkaz/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)